Stephen Seymour has been farming oysters in Drayton Harbor for years, handling water quality shutdowns, lawsuits and unhappy neighbors as aquaculture practices evolve.

“We’ve been farming up here since the mid-’80s,” he said of his company, the Drayton Harbor Oyster Company. “My son and I formed a for-profit business and then opened up a little oyster bar.”

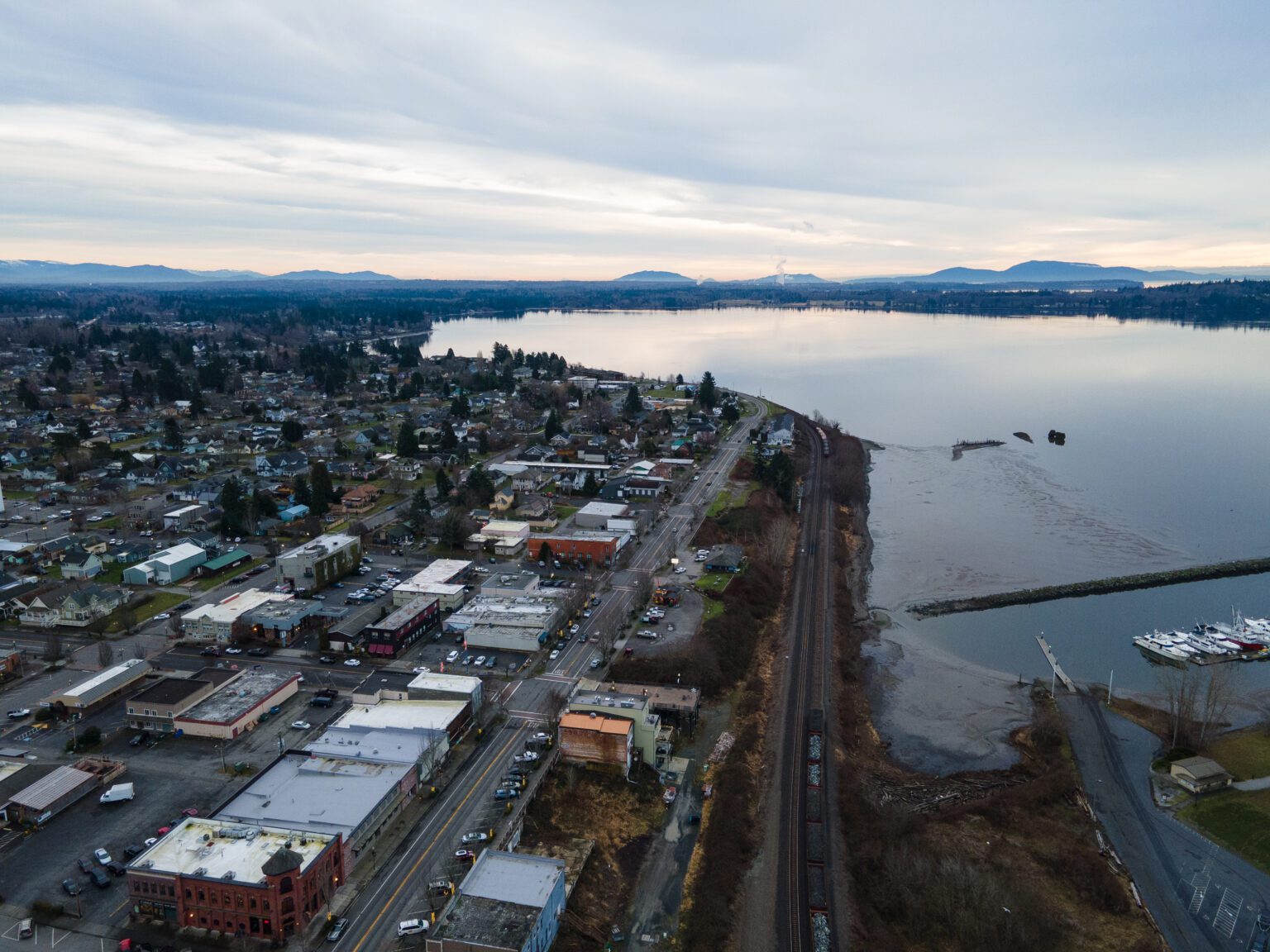

That “little” oyster bar has thrived in Blaine, drawing international crowds to the border town.

Seymour said visitors come from all over the country to their restaurant on Peace Portal Drive, where they can try Drayton oysters raw, grilled and fried, or incorporated into a sandwich or stew.

Now, the oyster farmer has taken the next steps in the oyster farming process and began submitting permits and applications for an 8-acre, off-bottom oyster farm in Drayton Harbor.

A new kind of farm

Seymour’s current farms operate in tidelands, producing hardened, healthy oysters. His proposed farm, though, will operate about 3,000 feet offshore.

“We’re looking to find the cleanest water so hopefully we can continue to farm for the next 50 years … and, in a lot of aspects, it is a cleaner way to grow our product,” Seymour said.

The off-bottom farm system allows the shellfish to grow without negatively impacting other parts of the habitat, like protected eelgrass and bull kelp.

Protecting kelp beds has been a priority for the state’s Department of Natural Resources, which recently established a “protection zone” for kelp and eelgrass in the state.

Shellfish farms have come under increasing scrutiny in recent years, with several lawsuits brought against the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers over a federal permit for the state’s shellfish industry.

In the past five years, hundreds of shellfish farmers lost their permits after a federal judge invalidated the Nationwide Permit 48, Commercial Shellfish Aquaculture Activities, in Washington.

“Washington state is home to unique and invaluable coastal ecosystems, which are unfortunately being threatened by the excessive expansion of industrial commercial shellfish aquaculture,” according to a December suit filed against the Corps, the latest in a string of lawsuits.

Despite the concerns, Seymour said his proposed farm would be an environmental win for the bay, as traditional farming methods do more damage than his proposed off-bottom farm.

“We’ve tried to address all the biological issues, and we’re reducing the impact on eelgrass,” he said. “The handwriting is on the wall: We should be looking for another farming system.”

Water quality concerns

Oysters are filter feeders, meaning they filter any waste found in the water in their habitats, often making them unsafe for human consumption. As a result, several beaches where oysters can be harvested in Whatcom are currently under advisory, while others remain closed. Of the 26 recreational harvest beaches in the county tracked by the Department of Health, only five are open. Another 15 operate under advisories or without evaluation.

Recreational harvest is not permitted around Semiahmoo and Blaine Marine Park, but commercial and recreational harvest is allowed in Drayton Harbor.

“In order to produce and sell shellfish in the United States, you’ve got to meet a certain criteria for water quality,” Seymour said. “In the case of Drayton Harbor, we got calls back in the early ’90s, late ’80s, because the water quality failed to meet that criteria.”

In 1999, Drayton Harbor was closed due to pollution and poor water quality tests. As a result, Seymour’s business closed down.

In 2004, the harbor reopened to shellfish harvest, but maintenance work continues to this day as humans and floods impact the ecosystem.

“It’s an urbanizing basin and people do things in the watershed that upset water quality,” Seymour said. “If anything makes me hesitate on our whole business model, it’s water quality. You’ve gotta have clean water or we’re out of business.”

Seymour said the proposed farm location is one of the cleanest sections in the harbor, but additional farms would help bring more attention to water quality issues across Birch Bay. Other off-bottom farms, like a proposed local seaweed farm, have been waiting on permit approval for years.

“The fact is, having shellfish businesses in the bay helps draw attention to water quality issues,” he said. “If nobody was farming out here, no one would care and pay attention. The bay would just slip into oblivion.”