Editor’s note: Title IX at 50 is a three-part series exploring and reporting on how the federal law has impacted the lives of Whatcom County women in sports over the past half-century. At times controversial, the legislation has gone a long way toward leveling the playing field for girls and women since its inception in 1972. Today’s Part II examines the legacy and influence of female coaches and athletes in Whatcom County. Due to broad public interest in this subject, this series has been made available outside the newspaper’s paywall as a public service by Cascadia Daily News. (Read Part I here.)

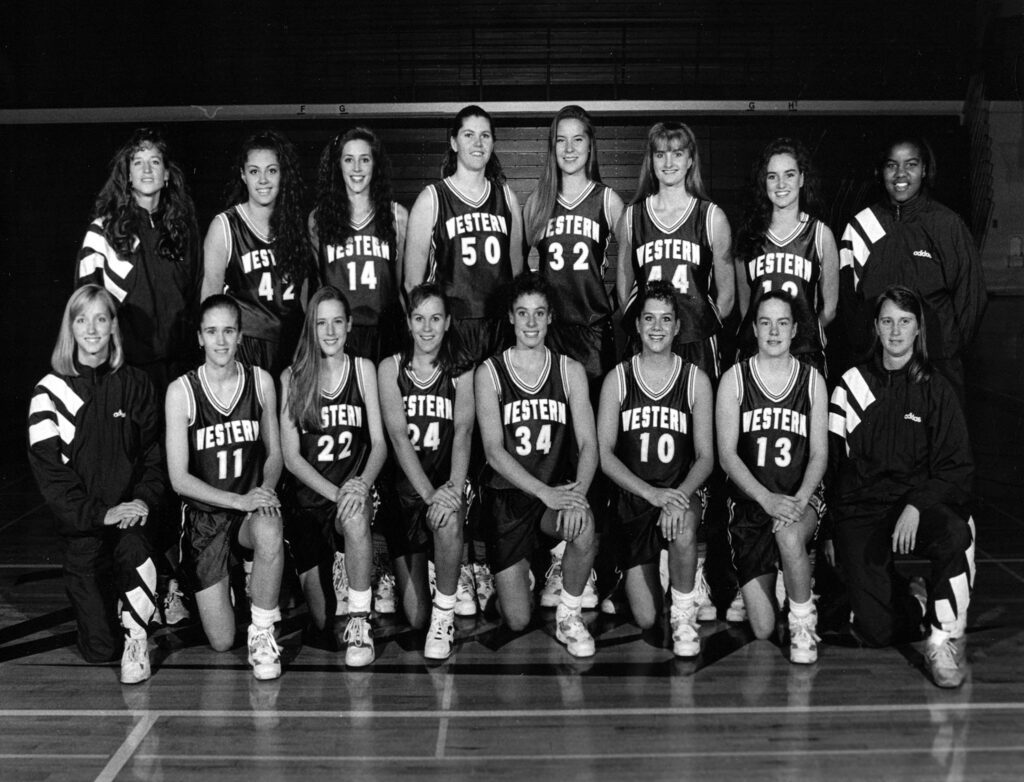

The majority of head coaches for Western Washington University’s women’s sports programs have been leading their teams since before the Vikings’ current student-athletes were born.

Pee Wee Halsell, Western’s longest-tenured coach, has been with the track and field and cross-country programs for 35 years, earning 22 Great Northwest Athletic Conference Coach of the Year awards and coaching 10 national champions. This year will be Travis Connell’s 20th season as head coach with the women’s soccer program, John Fuchs’ 25th with rowing, Carmen Dolfo’s 32nd with basketball and Diane Flick-Williams’ 22nd with volleyball.

Former Western athletic director Lynda Goodrich hired each of them during her time leading the Vikings athletic department.

“[Lynda] always said that her strength was really people,” Flick-Williams said. “It wasn’t about her management, necessarily, but she said she hired good people and let them do their thing.”

Each program’s consistency in reaching postseason play and recording winning records have kept coaches with the Vikings, but there’s more to it than that, Flick-Williams said.

In July, Flick-Williams looked around at the Western Volleyball Team Camp, held at Western’s Carver Gym for local high school teams to improve their skills and team chemistry before the fall high school season begins. She said around eight former Western alumni or coaches with ties to the Western program were in attendance as coaches, now running their own high school programs.

In fact, she said Megan Amundson, now the head of the Stanwood High School volleyball program, has been organizing an upcoming tournament featuring many of these Western-connected teams.

Flick-Williams said it’s dubbed “the Di-Fi Invitational, which was kind of a funny nickname they gave me.”

View a larger version of the timeline here

Western female athletes thrive as coaches

The number of female athletes graduating from Western to become coaches themselves — some at their alma mater, others at local youth programs — comes at a time when female coaches are still underrepresented in women’s sports programs.

This summer marked the 50th anniversary of the passing of Title IX, which prohibited discrimination in federally funded education programs, like sports. Though the number of girls and women participating in sports has increased dramatically over the past few decades, the percentage of women’s sports teams coached by women has decreased in the years since due to an influx of money into women’s sports programs, making their coaching positions more financially viable and more likely to be filled by experienced male coaches.

According to the Tucker Center for Girls and Women in Sport, women coached more than 90% of women’s college sports teams prior to 1972. The center’s 2019 report revealed that that number is now below 40%.

While many of these male coaches are qualified fits for their teams, there’s still a keen eye turned toward providing female athletes opportunities to continue within their sports as coaches, so young female athletes can see role models who look like them and feel represented within positions of authority in their sport.

“When women’s sports started to emerge, I didn’t feel we were doing enough — I’m talking nationally — about helping develop women in coaching positions,” Goodrich said. “I don’t think we did enough at the time to create assistant coach positions, graduate assistant positions, because you just don’t take an athlete who’s played the sport and then say, ‘OK, now you’re the head coach.’”

According to Western’s athletics website, in the current women’s and coed sports programs, 50% of assistant coaches and three out of seven head coaches are women. Western’s head-coaching numbers are on par with nationwide NCAA Division II numbers — 41.6% female for women’s and coed teams in 2021–22, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s Equity in Athletics Data. Nationwide data is slightly better for assistant coaches. Schools reported 54% female-identifying assistants for the same programs.

Women coaching women a ‘huge benefit’

“I truly believe there is a huge benefit to have women coaching women because who knows what it’s like to play at multiple levels in girls and women’s soccer besides someone who has been through similar experiences?” said Mary Schroeder, former Whatcom Community College women’s soccer head coach, youth coach and student-athlete at Western.

But these successful Western coaches — both men and women — could have left or been snatched up by larger NCAA Division I schools looking to bolster their coaching staffs. Several coaches said the support they receive at Western and the fact that the nearby area is a good place to raise a family keeps them at the school.

“Both of the athletic directors since I’ve been there, [Goodrich and, currently, Steve Card] have had a lot of trust in their coaches and they don’t micromanage things,” Dolfo said. “[They] really trust the process and the things that we’re doing.”

Women’s sports head coaches, on average, have a higher average annual institutional salary than men’s team’s head coaches at Western: $94,203, versus $77,273, in 2019.

Carmen Dolfo: ‘I thought I was so ready’

Several of Goodrich’s hires had never served as head coaches before filling the role at Western. Dolfo, who led Western women’s basketball to the national championship game last year, said stepping into the head coach role at 25 years old was odd, considering she was only a few years older than the upperclassmen players.

“I thought I was so ready,” Dolfo said. “I was like ‘Yeah, let’s go,’ like I had no reservations at all, and then my first year ended up being so hard … I was in [Lynda’s] office so much, trying to get help and just get suggestions on different things I could do. She never stepped over that line, she always let me come to her, but she definitely helped me through that process.”

Dolfo played for Goodrich on Western’s women’s basketball team, then came back to coach at her alma mater. Fuchs is also a Western alum, as well as Sheryl Gilmore, who is in her fourth season as head coach of Western’s softball team. A longtime local softball player, she transferred to Western to finish her degree after injuries put her softball career on hold at Edmonds Community College. She coached at Edmonds before Western and also co-founded the Washington Warriors Fastpitch Club, a travel softball team. These three are just a few examples of local coaches with longtime Western ties.

“I know I’m biased, but I think [our coaches are] some of the best in the U.S. You look at their records here, year-in and year-out,” Goodrich said. “They recruit really outstanding student-athletes, and then they coach them when they get them.”

Experienced coaches influence youth sports

Long-tenured coaches also shape Bellingham sports at the youth level.

Around 20 former Sehome High School gymnasts gathered on the shores of Lake Samish this July to celebrate the 100th birthday of longtime Sehome High School gymnastics coach Nola Ayres’ mother. One attendee flew in from Michigan. Another came from California.

Ayres, who coached gymnastics at Sehome High School for 25 years, led the program to 22 state titles, the most of any high school program in the nation.

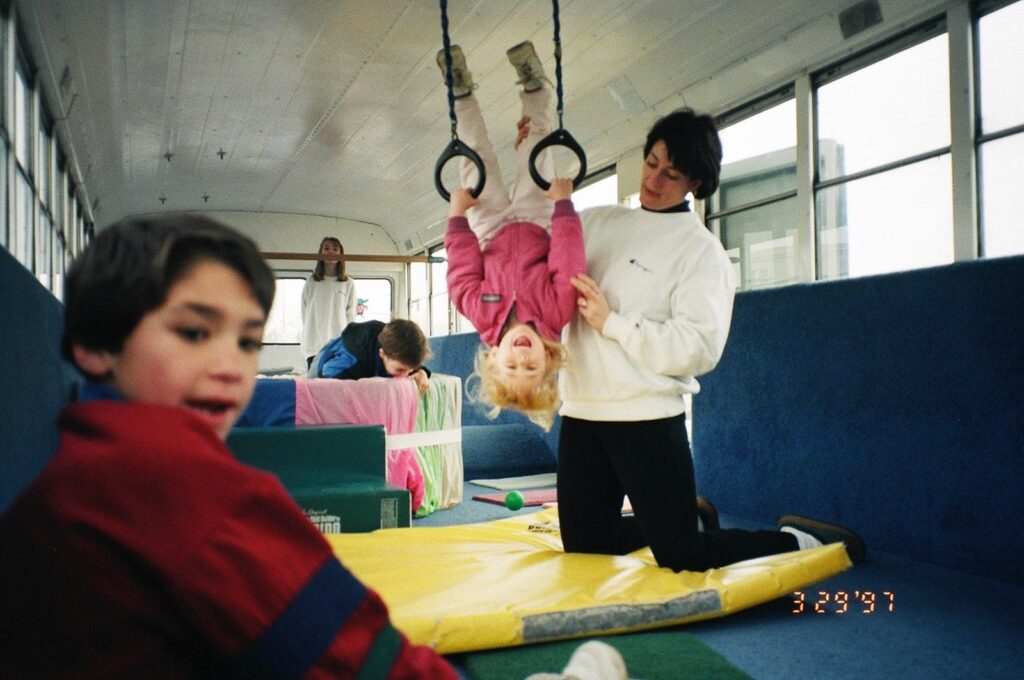

One of Ayres’ former Sehome gymnasts, Carolyn Saletto, also returned to Bellingham to coach — but not at Sehome. Out of a bus.

Saletto and her sister, both in foster care, had found a “safe place” and an identity in gymnastics at the YMCA and at Sehome, Saletto said. Passionate about physical fitness and dance, Saletto found herself coaching fitness classes and gymnastics as she moved around the world with her military husband before returning to Bellingham and coaching gymnastics. With the couple struggling financially to make ends meet, she said that, on their 10th anniversary, the pair sat at Lake Whatcom and wondered what was next.

“We sat and looked over the lake and cried, and we’re like, ‘What are we going to do?’” Saletto said. “I said, ‘Listen, I have been to business presentations about a mobile gymnastics program, and I think we can do it.’”

Gym Bus Lady opened door to local kids

Thus, in 1993, Gym Bus was born, and for 11 years, Saletto would drive to preschools and daycares to bring gymnastics to local children.

Gym Star was Saletto’s next undertaking, a sports center that offers gymnastics training, dance lessons and a preschool. Gym Star started with 30 kids, Saletto said, and now sees “upwards of 500 to 600 kids a week” with 96 kids enrolled for preschool for fall 2022.

“Hey, Gym Bus lady!” someone yelled to her, waving excitedly when she took her son to his first day at Squalicum High School years later.

“When you’re going into high school, you’re 14 or 15 years old, right? So that means I probably [taught] that child 10 years earlier,” Saletto said. “They have those fond memories. I want to make sure for anyone who went to Gym Star, or worked for me, that it was a positive experience.”

Recently retired, Saletto sold Gym Star to its now sister-gym, North Coast Gymnastics, in July.

Gymnastics’ Ayres battled stigmas with athletes, parents

Especially in the wake of Title IX passing, local coaching success also meant stepping outside the box and asking teams to put faith in strategies and training new to girls’ sports.

Ayres recalled having to convince Sehome gymnasts and parents to let go of stigmas around girls weightlifting, as the gymnastics team powerlifted with the football, basketball and wrestling teams, “for safety and because of the ballistic nature of the sport,” Ayres said.

One year, she took the gymnastics team on a training trip to China and taught sports psychology classes to Sehome athletes.

With athletes of any gender, coaching success should be marked not just by wins or professional accomplishments, but also by encouraging personal growth and enjoyment, said coaches like Saletto and longtime former Sehome tennis coach Bonna Giller. Giller’s no-cut tennis program at Sehome produced a legacy of state championships and large turnouts of 60–90 players for boys and girls seasons.

“At the end of the day, I always used to tell my kids, it’s not how far you go in your sport, or how many wins you have,” Giller said. “All you’re going to remember is how you felt about your participation and how it made you feel. Did you enjoy yourself? Did it add to your quality of life?”

For coaches like Flick-Williams, that enjoyment means seeing former athletes remain in or return to the Bellingham or Northwest Washington area and coach more athletes in the sport. Those new athletes, filling Western’s gym for July’s volleyball camp, may become coaches one day, too.

Next week: Title IX at 50 — What will Title IX look like for future sportswomen in Whatcom County?

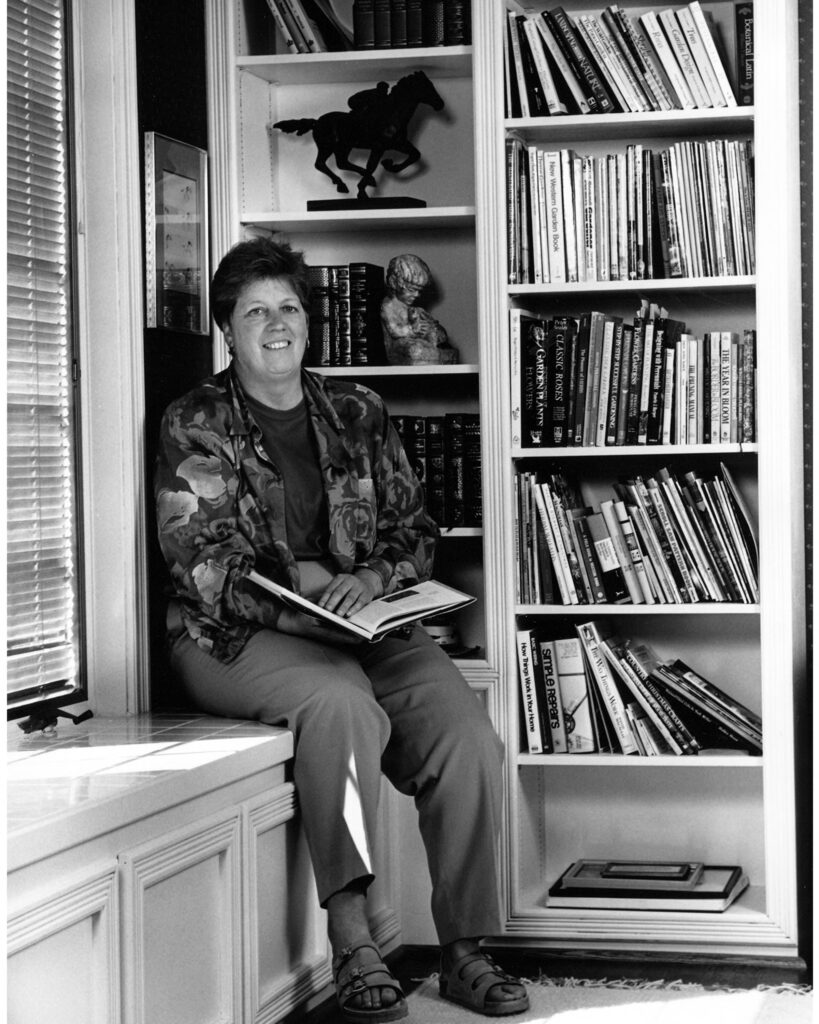

Profiles in Title IX — Lynda Goodrich: Female athletic director’s influence continues on today’s fields, floors, track

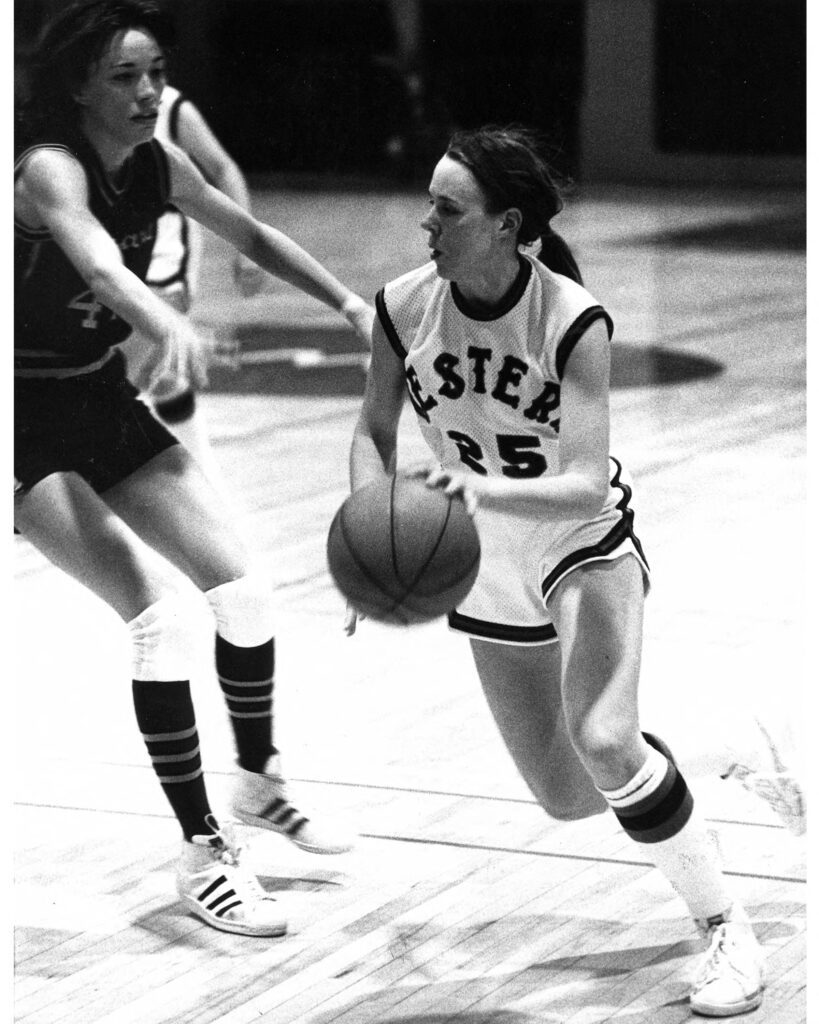

Western Washington University Athletics’ Impact Person of the 20th Century never even played varsity college sports at Western. Longtime Western athletic director Lynda Goodrich graduated with her bachelor’s degree in 1966. While a student at Western, she played field hockey and basketball, but the teams’ schedules and competitions were limited and unofficial in the years prior to Title IX.

Goodrich had transferred to Western with her sights set on a teaching degree, which she used to teach at Seattle High School for five years — working with other physical education teachers to start the school district’s interscholastic competitions for girls — before returning to Western for her master’s degree and a position coaching the basketball team as a graduate assistant.

Goodrich’s career as a coach and athletic director grew in the decades after Title IX’s passing, and she left an immense mark on Western’s athletics history while advocating for women’s sports at the university.

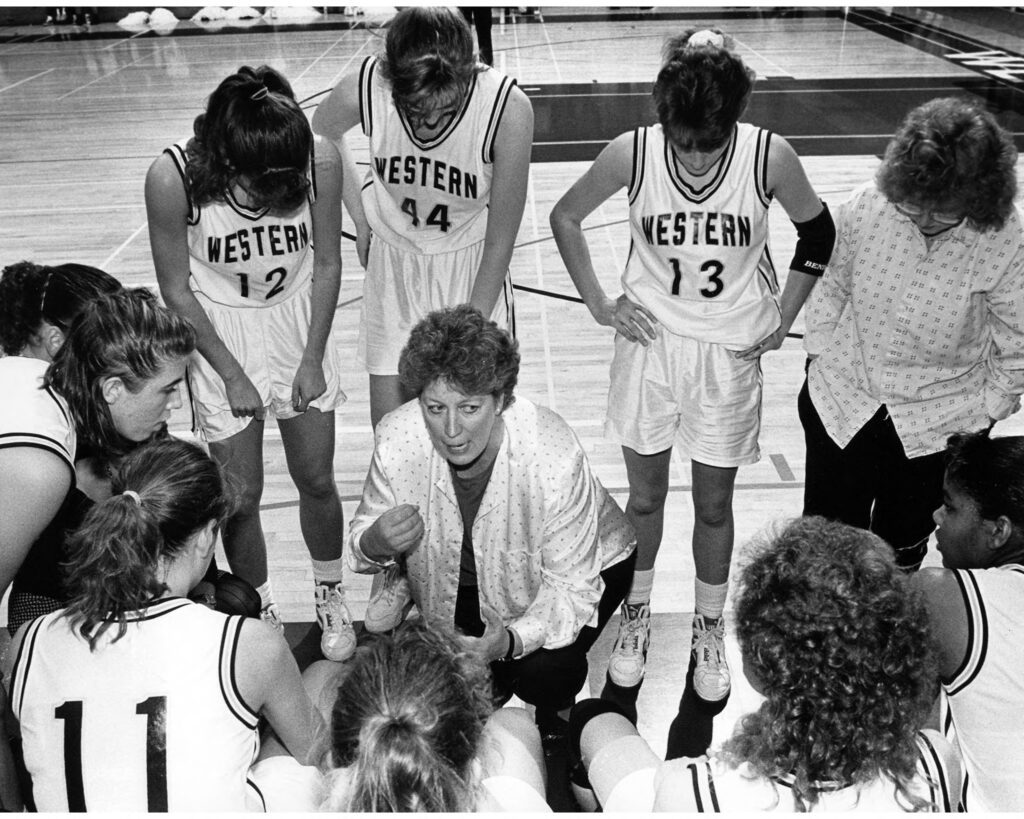

She first served as Western’s women’s basketball head coach for 19 seasons (1971–90), compiling winning records for each and postseason appearances in all but one. Goodrich also served as Western’s athletic director for 26 years, hiring several long-term coaches that lead Western teams today, eight of whom had never been head coaches at the college level.

“They made me look really good,” Goodrich said about the Western coaches. “I’ve always felt like I was a good judge of character and people, and so you make a decision and it’s worked out.”

Goodrich was named Western’s athletic director in 1987, when it was a rarity for a woman to run a men’s and women’s collegiate athletic department. It was a role in which she oversaw nine of the Vikings’ national championships and the school’s transition from competing in the NAIA to NCAA Division II.

“Success builds on success,” Goodrich said. “Once you have success, then that kind of perpetuates itself.”

Goodrich, who retired in 2013, was unanimously inducted into the National Association of College Directors of Athletics Hall of Fame. She was also a finalist for National Division II Coach of the Year — twice — and Whatcom County Sportsperson of the Year.

Current women’s basketball head coach Carmen Dolfo was a basketball player for Goodrich at Western, and Goodrich hired Dolfo to fill in her role after becoming athletic director.

“She’s really smart,” Dolfo said of playing for Goodrich. “She was such a good role model for women under her to have. She knew what battles to pick, and she definitely would battle things, but she also knew when to let things go.”

Goodrich said her biggest point of pride is students graduating and doing well academically. While much of college athletics has become “money driven,” Goodrich said, she’s glad Western, at the Division II level, can prioritize students’ education as well.

Profiles in Title IX — Sierra Shugarts and Taylor Peacocke: Playing overseas rewarding, but hard to make it a career

Success in college sports has taken several Western Washington University players beyond Bellingham — and beyond the United States. Their successful college careers, turned professional international opportunities, are part of a pattern for many female athletes post-Title IX.

Despite the increase in the number of female collegiate athletes over the past five decades, professional opportunities for female athletes are not regulated by Title IX in similar ways. Not only are most female basketball and soccer players paid less than their male counterparts in the United States, there are also simply fewer opportunities. Twelve WNBA teams field 12 players each, while 30 NBA teams can roster up to 15 players in the regular season. That means 144 spots in the pro women’s league versus 450 in the men’s.

It’s a similar picture for professional soccer. Thirty players make up a game-day roster for a Major League Soccer team, multiplied by 28 teams. That’s 840 Major League Soccer players — compared to the 244 National Women’s Soccer League senior-level players — 12 teams of 24 players each.

Combine the factors of pay and available roster spots, and it’s no wonder female athletes who shine at the NCAA level look overseas for playing opportunities. That’s what Western’s Sierra Shugarts and Taylor Peacocke did.

In soccer, defenders often fly under the radar and don’t get the nod for national player awards. Shugarts’ presence at center back for Western Washington’s women’s soccer team earned her the NCAA Division II Player of the Year award in 2016, making her the first defensive field player to ever earn the honor.

That year, with Shugarts as a captain, the Vikings won the NCAA Division II national title with a 3-2 win over Grand Valley State, avenging 2015’s semifinal loss to the same team by the same score.

The Western soccer team had made it to the national tournament but lost in early rounds in Shugarts’ first two years, but Shugarts said the team entered her junior season with a class of talented freshmen and “this momentum that was already setting the bar … started with the seniors and juniors that were there when I was a freshman.”

“We all just were on the same page,” Shugarts said. “There was no question that we weren’t going to win, if that makes sense. We were all very much dialed in, like we knew what to expect … You could just feel that energy every single game, which was a really cool feeling. I don’t think I’ve ever been on a team that has been so in tune, not even just on the field, but off the field as well.”

Semi-pro, then to Sweden and Czech Republic

Shugarts, an in-state youth player with Washington Premier’s Elite Clubs National League team, played with the Seattle Sounders semi-professional team. She also played in Sweden for two seasons and in the Czech Republic for another season after graduating from Western, switching positions from center back to central midfield to outside back, which elevated her game, Shugarts said.

“[The Czech Republic] was probably like the highest level of soccer I had played,” Shugarts said. “The girls were really good there, and a lot of the girls were on the national team.”

Just before the COVID-19 pandemic, Shugarts decided to return to the U.S. full-time, and is now working as a model, social media manager and content creator. Shugarts said that playing overseas was rewarding but financially challenging, with low pay and difficulty finding temporary work when in Washington for the offseason.

“I had enough to live but not enough to save,” Shugarts said. “I was like, ‘Well, you know, as much as I love the game, like I don’t think that this is something that is sustainable for me moving forward.’”

Like Shugarts, Peacocke had a stellar 2016 at Western. That season, 2016–17, the women’s basketball guard led NCAA Division II in scoring, averaging 23.3 points per game and breaking Western’s single-season points record. Peacocke earned First-Team All-American honors and led the Vikings to a 26-6 record her senior year.

Despite attending a professional basketball combine her senior year and receiving some overseas offers, Peacocke decided not to play internationally at the time. She wanted to see how she stacked up against top Division I players — “that competitive side of [her] coming out” — but was unsure about the financial longevity of going pro.

“I think a part all women in sports understand [is] that the ceiling for us is so much lower than it is for men,” Peacocke said. “Things are changing and things are getting better, but it’s not something that I could do for 20 or 30 years. It’s not something that I’m going to make millions of dollars and do well for myself in the long term. I think the rational side of me kind of put limits to myself and was like, ‘I should be doing something more with my life, I should be getting a master’s and setting myself up for the long term.’”

Player turned coach, then a scary diagnosis

She returned to Western basketball as a grad assistant before serving as an assistant coach at Western New Mexico University, then coaching at her alma mater high school, Inglemoor in Kenmore. However, in 2019, the same year Peacocke stepped into a coaching role at Inglemoor, she was diagnosed with cancer.

The large B-cell lymphoma and superior vena cava syndrome diagnosis, Peacocke said, put previous basketball choices in perspective for the young coach.

“The time is so short,” Peacocke said. “I didn’t know if it was possible to keep playing, but I realized, like if I was going to, I was going to have to do it now. I didn’t want to lose the opportunity a second time because I was worried about long-term future stuff that I can figure out later on.”

With the help of her family and coaches, Peacocke began her treatment — and training to reach game fitness.

Treatment and gritty recovery

“It was really kind of a crawl-walk-run mentality where you’re just doing whatever you can in a day and kind of shifting your mindset about, ‘It’s not how much you’re doing. It’s just about the progress,’” Peacocke said. “I think like, as a high-level athlete, you’re so conditioned in your head [that] more is better and push through and all those kinds of things. It definitely taught me to listen to my body and slow down. There were a lot of days of five steps forward, and then the next day you wake up and your body just isn’t there … It’s really more of a mental thing to keep pushing through, versus physical.”

After about six months, Peacocke said, she was feeling “pretty good,” as an agent began helping her look for teams abroad in early 2021. Scorers First Sports Management was upfront with Peacocke, telling her it might be difficult to secure a signing for someone with her health history and four years since her last competitive basketball start.

But in May 2021, Peacocke signed a contract with S.L. Benfica in Lisbon, Portugal, which was coming off a league-championship season. Peacocke played with the Portuguese team from October 2021 to May 2022, helping it to another league title.

“We had five or six people averaging double-digits or close to” in scoring, Peacocke said. “When you have a team of five, six, seven people that can go off at any point, it really is impossible to figure out how you game plan for that.”

‘You just figure out how to do it’

Peacocke said she enjoyed getting to know Portugal and her teammates, most of whom were local Portuguese players.

“It’s the idea of just throw[ing] you in the fire, and you’ll figure it out,” Peacocke said. “I was so intimidated to go to the grocery store day one, and you just figure out how to do it. Google Translate is your best friend, and then before you know it, you’re talking to locals and understanding some of the language … I got so comfortable so quickly and established a new routine and a new place that really felt like home away from home.”

After 10 months in Portugal, Peacocke has returned to Washington and is coaching at Inglemoor. The long professional season and distance from home prompted the decision to stay in the U.S. and coach this season.

“A lot of the girls [on the Inglemoor team] were like, ‘Are you leaving again?’” Peacocke said. Peacocke found it hard to tell the players anything but no. She has found herself enjoying coaching, she said, which came as a surprise. When she first arrived at Western, she admitted to being a player who was a “little spitfire, and very stubborn and feisty” — and one who butted heads with legendary head coach Carmen Dolfo. By the time Peacocke graduated in 2017, her relationship with Dolfo had transformed. So had Peacocke.

College coach ‘allowed me to flourish’

Dolfo, Peacocke said, “will be at my wedding someday … She’s one of the most influential, most important people in my life. She allowed me to flourish in that environment because she let me be me while also giving me respectable boundaries.

“As an 18-year-old kid, you think you know best. So you come in and you … think things should be a certain way and you don’t always see the bigger picture or the four-year process.

“Carmen was great because as much as I drove her crazy, she truly always took the time to understand things from my perspective and helped me widen my lens and understand … it’s more about the process of developing you as a person and player.”

Peacocke, through playing professionally and coaching, found a way to stay connected to basketball. Shugarts, too, continued her soccer journey overseas. Along the way, the pair had to weigh the dreams of playing professional sports with the realities of being a female athlete: How long can you play? Where are there opportunities? Is this a financially viable career path?

Even if their competitive days are over, they both can take what they’ve learned from their own experience and create a career.

“I instantly fell in love with [coaching] and realized that even if I can’t play or I’m not always going to play, I can always be attached to the game somehow,” Peacocke said. “It’s just so rewarding seeing kids from start to finish of their careers, and so it’s kind of that full-circle moment.”

Profiles in Title IX — Monika Gruszecki: NCAA national champion to NCAA compliance officer

Before Monika Gruszecki was throwing javelins to win NCAA national championships, she skipped rocks on the beach. Growing up, she would camp with her family at Whidbey Island, where the beaches are flat, “perfect for skipping rocks,” Gruszecki said. This summer, she returned to that beach for her mother’s birthday, and she caught herself throwing rocks again.

“This is how it started,” Gruszecki said. A little girl, with her family, competing to see who could skip rocks the furthest into the deep blue. “Those throwing mechanics, they get developed early on.”

Less than 100 miles north of Whidbey, at Western Washington University, Gruszecki competed and won two NCAA Division II national championships in javelin, one in 2007 and the other in 2011. After balancing law school and training for the Olympic trials in her post-grad years, Gruszecki is now the director of NCAA compliance for the University of Arizona.

Gruszecki won her first national championship in her freshman year.

“[Coach Pee Wee Halsell] has a really great way of just keeping people focused and not amping themselves up too much,” Gruszecki said. “The game plan for the nationals back in 2007 was simply throw far, do your best … I think that’s what makes those kinds of Cinderella stories possible, when you’re just living in the moment and enjoying the experience.”

Her second championship came in her senior year in between living in Germany.

Gruszecki, studying English and German, wanted to become fluent in the language. For the 2008–09 school year, she told Halsell she was going to study in Germany. She wasn’t sure if she’d be back with the team the next year, or at all.

“It was a very adult conversation,” Gruszecki said. “He said, ‘If you ever want to come back, you’re always welcome.’ And sure enough, I did.”

After returning to Western and winning her second national title, Gruszecki would later return to Germany to train with Petra Felke, her javelin idol, in preparation for the 2016 Olympic trials. She had trained for the 2012 trials as well, working odd jobs in her first post-graduate year to support her javelin career, but had torn a ligament in her elbow before the event.

In the gaps between the two Olympic trials, Gruszecki balanced training with law school at Gonzaga University. She would get up at 6 a.m. to train, or trained after class, and had the lowest data plan on her cell phone to limit distractions. It was a consistent “small daily effort” more than one big moment of inspiration, she said, though she fell asleep on her textbooks more than once.

“When I got home it would just be, you know, turn on the radio, listen to some music, have friends over, cook food and pass out,” Gruszecki said. “My boyfriend asks me, ‘How come you didn’t date anyone for so long?’ I didn’t have time.”

She wasn’t sure what kind of law she wanted to go into for most of her time at Gonzaga, but when she took an administrative law course, then spent six months researching the Russian Olympic doping scandal, her interests in law and sports began to blend.

At the 2016 trials, standing on the javelin runway in Eugene, Oregon — Track Town, USA — Gruszecki recalled thinking, ‘This is an administrative agency,’ which she said wasn’t quite the right headspace to be in before an Olympic trial. Looking at the old historic Hayward Field, she thought about the people who dedicated their careers to making sure track and field thrived.

“I want to be in athletics in general, because of how special and delicate of a thing this is, and how important it is to have the right people who are working in this industry,” Gruszecki said. “A few small rule changes … there’s a whole lot of things that can happen from one year to the next. Those can have huge impacts on the availability of the sport and how future generations have access to it.”

Gruszecki interned with NCAA compliance before working with NCAA rules and regulations at her current position at the University of Arizona. The work affords her a unique perspective on college athletics, having seen changes since her time at Western. She said recruiting opportunities are often more accessible, with new technologies, and that today’s social media would have drastically shaped her own college experience had she been competing now.

Series Credits

Reporter Cassidy Hettesheimer was a summer quarter sports intern at Cascadia Daily News. She is majoring in journalism and studying sports media at the University of Georgia, where she contributes to the photo and sports desks of the student newspaper, The Red & Black. Cassidy loves running, reading, playing soccer and photography.

Title IX at 50 project editor Meri-Jo Borzilleri is a 30-year journalist and tomboy from the 1970s who, to this day, still needs to play.