Editor’s note: Title IX at 50 is a three-part series exploring and reporting on how the federal law has impacted lives of Whatcom County women in sports over the past half-century. At times controversial, the legislation has gone a long way toward leveling the playing field for girls and women since its inception in 1972. Today’s final part of the series examines what Title IX will look like for future sportswomen in Whatcom County. (Read Part I here. // Read Part II here.) Due to broad public interest in this subject, this series has been made available outside the newspaper’s paywall as a public service by Cascadia Daily News.

At first, it looked like an empty horse barn. However, crunching down the gravel driveway toward the Bike Ranch revealed that, instead of stables, the barn’s roof covered a carefully sculpted swath of dirt, formed into gap jumps and berms. A fire pit sat dormant in the center of the pump track, surrounded by plastic lawn chairs that rattled as a teenage girl on a bike zipped by, turning a tight corner, gracefully in control of her mountain bike.

“Dropping in!” shouted another biker. She edged her bike forward, down the ramp near the entrance of the track and began her loop around the barn.

These riders are a part of Radical Rippers, a mountain biking program for junior girls, put on by local coaches like Angi Weston. The program’s three-day summer camp welcomes all young female-identifying and nonbinary riders, and gives the campers a chance to learn mountain biking basics and hone advanced skills at the Bike Ranch while progressing onto paths at Galbraith Mountain and Lake Padden.

Weston began Radical Rippers as an addition to the local Flying Squirrels after-school mountain biking program for girls. Weston hopes to create a safe, inviting environment for girls looking to enter a traditionally male-dominated sport, though she also added that Bellingham, compared to other regions where she has coached, has more gender diversity within its mountain biking community.

“Radical Rippers makes me feel more included,” biker Charly Eggert, 13, said. “When I was doing wrestling, it was an all-boys team and it felt a little bit more isolating, and so [it’s nice] having a girl group of people who have the same problems or the same interests and go through the same things as you.”

Title IX, the 1972 law which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in federally funded education programs, supports equal treatment of female athletes in schools and other state-funded programs. But the reality is, sports extend past that, especially in an area like Bellingham, where residents are tuned-in to outdoor and recreational activities like biking, paddling and hiking. Thus, local coaches like Weston look to push against the legal limitations of Title IX’s reach and help girls and women break into these recreational sports through private coaching and camps.

Another reality: Title IX, even with the immense progress made over the past 50 years, hasn’t solved every problem in girls and women’s sports. These often-nationwide limitations — and the local people looking to solve them — are a part of the sports landscape in Bellingham as well.

Women’s semi-pro soccer seeks to boost diversity here

One limitation is a matter of accessibility — more girls and women are participating in sports, but which girls and women? Suneeta Eisenberg, who founded the Whatcom Waves semi-pro women’s indoor soccer team in 2021, said that growing up, she rarely saw female athletes who looked like her or shared her cultural upbringing.

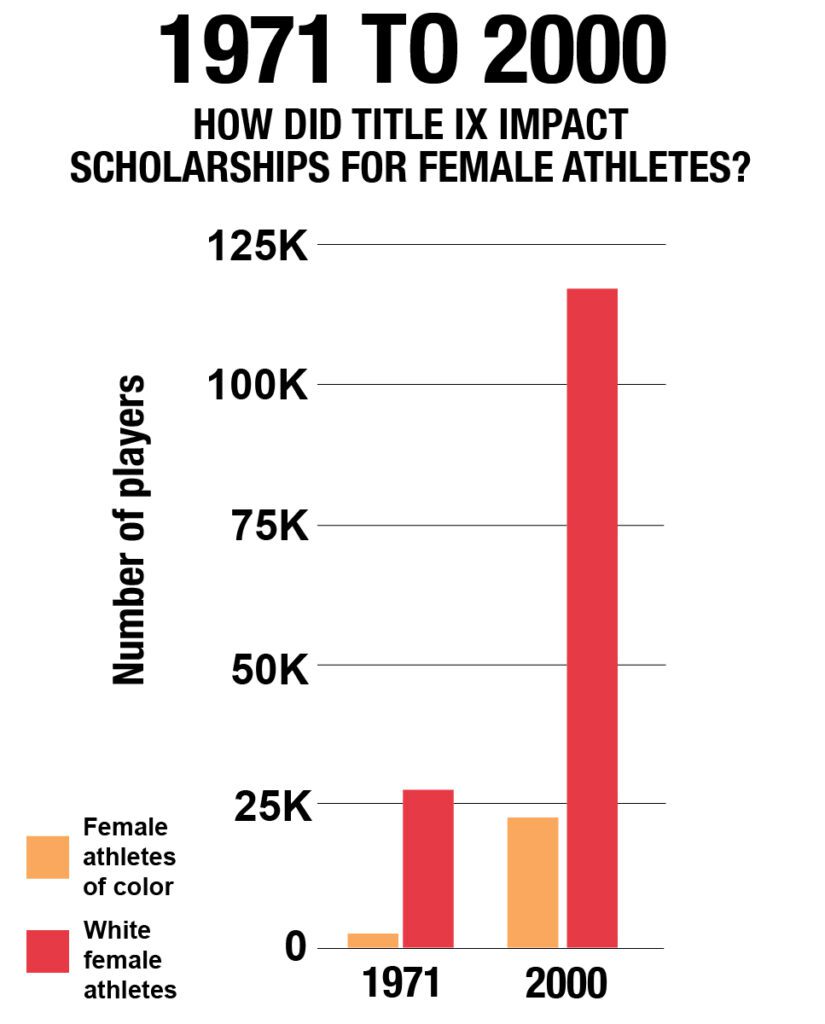

According to the Women’s Sports Foundation (WSF), “girls of color, girls of lower socioeconomic status, and girls in urban and rural areas” participate in sports less often and, when they do, they, on average, drop out earlier than their white, suburban, or socioeconomically affluent peers. Girls of color in urban areas had a drop-out rate twice that of suburban white girls, which the WSF noted was often tied to a lack of resources and programs.

“A woman of color doesn’t get the same opportunities as other women out there,” Eisenberg said. “I’ve been playing in the [local] outdoor [soccer] league for 12 years, and you kind of notice, like, ‘Oh, there’s no one [with] really a Black or brown or Indigenous background here.’”

She hopes that the Waves, a new chance for local female soccer players to continue to the semi-pro level like the men can with Bellingham United FC, can provide some of that representation to young girls and bring in community partners that advocate for diversity and inclusion.

The Waves adds to the list of local women’s or womxn’s teams that adult athletes can continue participating in, including the Chuckanut Bay Rugby Club and the Bellingham Roller Betties roller derby team.

Womxn teams — versus women’s teams — are often named as such to be intentionally inclusive of trans and nonbinary athletes. While the Biden administration has looked to more broadly interpret laws that protect LGBTQ+ workers and students from discrimination, including trans athletes, as of late September the federal government was in the midst of its official ruling on how Title IX applies to trans athletes looking to participate on sports teams. Currently, 18 states have laws barring trans athletes from participating on sports teams matching their gender identity.

Leadership gap in college athletics

In general, it helps if young athletes of color see people like themselves in leadership positions, like coaching or administration. But role models are scarce. A study of college athletics by the Women’s Sports Foundation shows of the 42.5% of college coaches who are women, just 4% are women of color. Women make up 17% of college athletic directors, and only 1.7% of them are women of color.

Jadyn Watts, a freshman on Western Washington University’s women’s basketball team from Seattle’s West Seattle High and Mt. Rainier High, grew up in a basketball family being coached by her dad, who she describes as her role model. Her mom and dad played NCAA Division I basketball.

But throughout club and school programs, she rarely saw Black female coaches, or even many female coaches at all. While playing in a club national championship tournament, “we definitely played teams that were more diverse, but they were coached by men as well,” Watts said.

Now she is being coached by longtime Western coach Carmen Dolfo, and in just a few weeks, already notices a difference. “There’s just such a big difference with the player-coach relationship playing for Carmen. She’s just such a better communicator than I’m used to. And so it’s already been awesome. She has more perspective on what we’re going through. I’ve just never really experienced that with a male coach.”

Watts is one of three freshmen players of color listed on Western’s roster this season in a program that is making more diversity a goal.

“I have talked to Carmen and she has expressed that she’s definitely committed to making that change,” Watts said.

Mountain biking mostly white and wealthy

Weston said mountain biking, at least in the spendy-gear realm, has also been a predominantly white and wealthy sport, central to mountain towns with an expensive cost of living. Groups like Vamos Outdoors work to connect Latinx and English Language Learner families to outdoor opportunities, like mountain biking.

“All of us cozy white people with money, it takes us stepping up, getting out of our comfort zone, experimenting with new approaches to bringing more people into the sport,” Weston said.

Accessibility also can come down to a matter of money, considering both the individual paying for training and the sponsorship money put behind local events to reduce costs for participants. Outdoor sporting gear can be expensive, and community investment in sports programs may help alleviate the costs for interested participants.

“If you go with a tennis club, and you want to learn how to play and if you want to compete, it’s going to cost you thousands of dollars,” former longtime Sehome tennis coach Bonna Giller said.

Summer leagues highlight affordable tennis

This past summer, Angie Harwood, head tennis coach at Squalicum High School, organized a weekly summer tennis league that cost just $40 for five weeks where high school girls could train and compete. By the end of the summer, nearly 40 girls participated in singles and doubles play.

In 2018, Prime Sports Institute leadership coach Erica Quam started a National Girls and Women In Sports Day event in Bellingham, after talking to friend Courtney McBean, who is involved in youth lacrosse. The pair discussed how the community could benefit from a space for young girls to grow their athletic confidence and to see “all the different opportunities they have to play,” Quam said.

Washington State University, where Quam coached swimming, had hosted an event for National Girls and Women in Sports Day in February each year.

At the first Bellingham version of the event, hosted in Bellingham High School’s atrium, young attendees could listen to local speakers and try out different sports. Elementary and junior-high students scored on a hockey net, tried on mountain biking helmets, ran relays and tied sailing knots, all with the help of high school and college athletes. Later versions of the event were held at Whatcom Middle School until the COVID-19 pandemic, when it moved to online seminar-style talks.

A future for annual Girls and Women in Sports Day?

Quam said an annual Girls and Women in Sports Day event could grow and expand with more community involvement and sponsorship so more participants can join in with more options.

“I’d love to see an organization sponsor [the event] and be the title sponsor,” Quam said. “We’ve had to just scrape for donations and rent out the facilities ourselves … The collaboration piece in this community is just so valuable.”

Weston has seen the impact of sponsorship. In 2008, while coaching in West Virginia, she began Women’s Weekends, two-day programs that allowed female-identifying mountain bikers to gather, train, learn and ride.

After securing a sponsorship from Transition Bikes, Weston said the cost of the event could be lowered from an estimated $600 or $700 per person to around $400, with demo bikes available for new riders who might not yet be ready to commit to an expensive mountain bike that can range from $1,000 to $11,000.

“[Transition was] stoked on my women’s events, and they just really wanted to support it,” Weston said. “I was already doing these Women’s Weekends events, but it was all funded on my own by the registration fees. To hire really great coaches — that costs a lot of money … We have small groups; it’s intimate.”

Carolyn Saletto, former owner of the Gym Star gymnastics program, said the “family-oriented” nature of Whatcom County encourages many local residents to “get behind their kids” and support them in the commitment it requires to get to practice and invest in youth sports. The outdoor culture of the area as well — trail builders creating mountain bike paths, the surf ski community, youth paddling teams — is key to creating lifelong athletes, Saletto said.

“I think it’s a combination of the people in the place,” Saletto said. “It seems like people come to Bellingham to appreciate the outdoors and participate in it, so it’s not just the organized sports within the schools and within the high schools. There’s a lot of opportunity for non-traditional sports as well.”

Referee shortage crimps rec sports locally

As more girls and women participate in sports, there’s also the concern of personnel — coaches and officials — to support increasing numbers. Nationwide, both boys and girls sports face a shortage of referees. According to a 2019 story from The Seattle Times, the Washington Officials Association lost more than 1,500 members in the previous decade and sat at just over 6,000 for the 2018–19 school year. Basketball referees decreased 12.2% in the three years prior to 2019, and the officials-to-athletes ratio is “at its lowest on record,” with many referees citing lack of respect, long hours and low pay as reasons for the unprecedented departures.

Saletto and longtime Sehome High School gymnastics coach Nola Ayres both stressed the need for education and training for new coaches and officials, especially in highly technical sports like gymnastics. Ayres attributed some of her long-term coaching success to working as a gymnastics judge, gaining more insight into the sport’s scoring and passing along what she learned to Sehome’s gymnasts. Even now, in retirement, she flies across the western United States to judge college meets.

“It’s hard to get officials,” Ayres said. “In gymnastics, you are giving up your whole weekend. And like for myself, my gymnastic schedule will start in November. And I will not, except at Christmas, have a weekend free until the first of May.”

Saletto said due to a lack of personnel and facility space for expensive gymnastics equipment, many high schools have started dropping gymnastics programs, and gymnastics opportunities nationwide have shifted to club programs that have more money and space to devote to the sport.

Coaching the coaches is key

Weston has been training local mountain biking coaches, and Quam works with coaches to improve their development and leadership strategies.

“I have coaches that travel from out of town to come take my coaches trainings,” Weston said. “I’ve been coaching director for different programs that have events going throughout the country, so I’ve trained coaches from coast to coast in our country.”

Refereeing and coaching shortages impact both boys and girls sports, as do current discussions about the culture of youth sports. In 2019, The Atlantic reported that many sports and psychology experts are concerned about the “professionalization” of youth sports, with more youth athletes suffering from sleep loss, anxiety and overtraining than in decades prior. Children and teens may find joy and confidence in their sport if they’re able to strike the right balance, but it’s often a fine line, for both girls and boys.

“Even in high school, even in middle school, it’s become a business,” Giller said. “You’ve got to be on these elite teams and training year-round and kids don’t get to be kids.”

For Saletto, it’s a matter of having coaches who see not only the potential of children as youth athletes, but as human beings. She said some programs view children playing multiple other sports as competition to their own gyms or teams.

“Sacrificing a young person for gold should have never been acceptable,” Saletto said.

Several of the bikers zipping around the Bike Ranch in early August were multi-sport athletes. Charly and Johnny Eggert, both 13, participate in cross country and wrestling, respectively. Georgia Russell, also 13, plays lacrosse and skis in addition to biking.

“I like to do multiple different sports because, for biking, for me, I see myself doing it forever,” Russell said. “I’ll do [it], like, the rest of my life probably, but the other sports … I’m probably not going to be able to run that much forever. I like having a schedule and spreading my time through different stuff and getting to know different kinds of people.”

It’s a matter of making sure that all girls and women have these opportunities to try multiple sports, compete in safe and well-staffed environments and see community support behind their endeavors. Title IX, in its current form, might not guarantee these complexities, but it lays a foundation and lights a torch to be carried forward.

Series Credits

Reporter Cassidy Hettesheimer was a summer quarter sports intern at Cascadia Daily News. She is majoring in journalism and studying sports media at the University of Georgia, where she contributes to the photo and sports desks of the student newspaper, The Red & Black. Cassidy loves running, reading, playing soccer and photography.

Title IX at 50 project editor Meri-Jo Borzilleri is a 30-year journalist and tomboy from the 1970s who, to this day, still needs to play.