Editor’s note: Time to Spare: Bowling clears a lane for sport, community is a three-part series that explores league culture, highlights women bowlers, and details the impact of bowling alleys closing and the history of the sport in Whatcom County. Part three details how local bowling center owners and avid bowlers contribute to the future of the sport and the space it takes to play it.

In early April 2008 — I was 10 — Ballard’s Sunset Bowl closed. A real-estate developer bought the property for $13.2 million, according to The Seattle Times.

Sunset’s building sat empty for years with a chain link fence around it, and I don’t remember when they tore down the rainbow-painted exterior and started building the mammoth condominium on the lot because I refused to look at it when we drove by. The condo replaced my home away from home — where I learned how to bowl as a toddler and won my first league with my dad.

It wasn’t the first Seattle bowling alley, and de facto community hub, to unleash strong emotions as it was swallowed up by “progress.” On its final night two years prior, a bagpiper at Leilani Lanes administered last rites via “Amazing Grace” in the tiki-themed center as bowlers slid up and down the oiled lanes, crying.

Today, during league at Bellingham’s 20th Century Bowl, I find comfort in a little-known secret: The air compressor that runs the bumpers there is originally from Sunset, where equipment was auctioned off after the doors closed.

20th Century’s owner, Beth Brannian, said the alley also has a drop safe from Leilani Lanes, a “BOWL” sign from Everett’s Tyee Lanes and masking units from Renton’s Hillcrest Family Bowling Center.

Bowling alleys, it seems, tend to drop like flies.

Closed bowling centers leave open wounds

In 2020, San Juan Lanes in Anacortes — which, in 1960, had an assessed value of $12,927 — closed and the property was bought for $2 million. Nearly six months later, a former employee purchased the center’s notable bowling pin sign because he “couldn’t fathom” it would ever shut down.

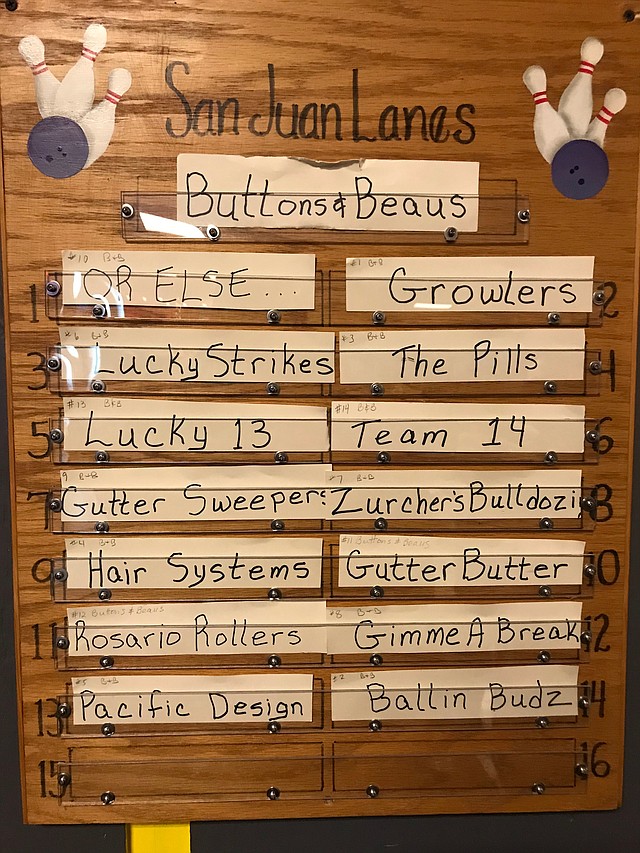

Like every other shuttered bowling alley, San Juan Lanes sold its equipment, bowling balls, lanes, signs and more to anyone looking to buy. One nostalgic item went to avid San Juan Lanes bowler Emma Donohew, who now bowls regularly at 20th Century and called the closure of her old home lanes “devastating.”

Donohew and her husband, also a bowler, scored the wooden board that used to list league team names. A bittersweet moment was when they saw the last teams written on the board, which included their team right before COVID-19 shut the lanes down. It was a “piece of time,” she said.

The closure was a loss for Anacortes and the surrounding community, Donohew said, and it made 20th Century and other nearby centers “even more important” to her. In her mind, bowling alleys and other community spaces, such as swimming pools and roller skating rinks, are few and far between nowadays.

“When you lose those third spaces where there’s an intergenerational connection,” Donohew said, “where do those people go?”

Bowling, which is often associated with blue-collar workers, attracts a diverse and wide age range of people. Donohew doesn’t find the sport or the space it requires to be a luxury, but instead, a community space that offers life skills and coordination to everyone who walks in the doors.

“I always worry, are we going to be able to recreate that?” Donohew said. “I think bowling alleys have a sense of the sacred to them because they can’t be replicated very easily and that’s what makes something special.”

A pastor at Bellingham’s Echoes Church, Donohew said that while church or other community gatherings can happen anywhere, bowling is unique in that it has to happen in the confines of a bowling alley. “I know what it’s like to see a pit in the ground … I’ll chain myself to this bowling alley if I have to,” Donohew said, laughing.

Donohew is not the only leaguer who feels so strongly. Lacey Thompson, another 20th Century leaguer, said the only reason the center is still open is because of owner Beth Brannian, and not because the business lines her pockets.

“She keeps that business alive because she enjoys doing it because it brings joy to so many people. She is a very community-oriented person. Beth’s like family,” Thompson said. “So as long as she owns it, it’s gonna be open.”

How one Whatcom County bowling center stays in business

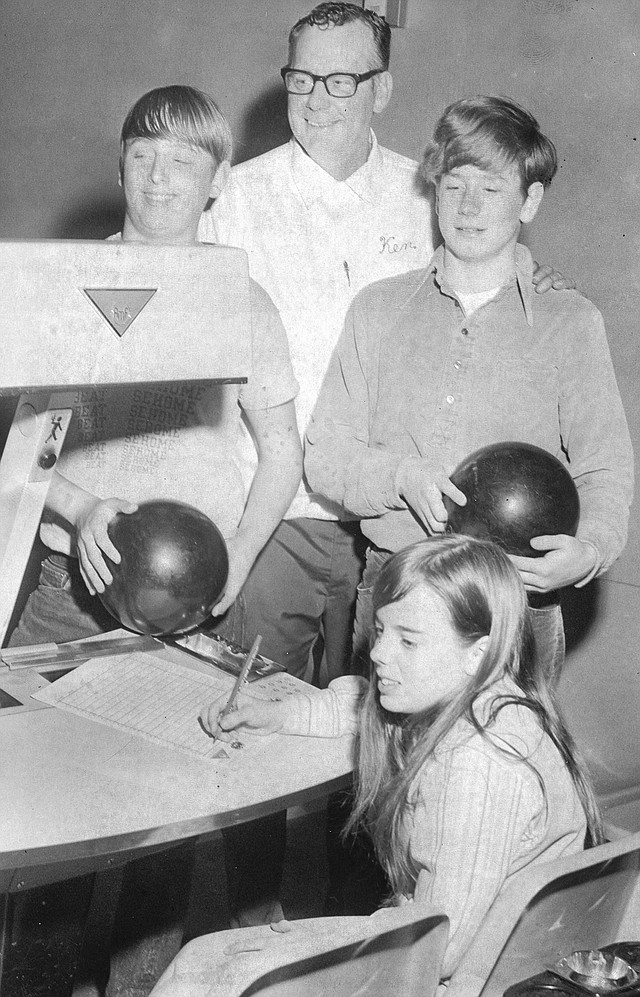

Brannian, like most bowling center owners, inherited 20th Century from her parents. Initially located on Railroad Avenue in downtown Bellingham, 20th Century launched in 1956 — before Brannian was born — by her father, Dick Brannian, and his three partners, who Dick bought out by the time his daughter graduated from high school.

Brannian worked there as soon as she turned 16 and continued working full-time until her father retired in his early 70s. They sold the business in 1989. The new owners missed so many payments after eight years, Brannian said, they owed more than they bought it for.

Her parents were financially unstable and her father was dying of cancer, Brannian said. She decided to buy 20th Century back, repossess it and sell the real estate. Using a “huge” credit line, she got it back in 1997.

“When you’ve repossessed a business, you have absolutely no money. [We] were hoping to close,” Brannian said. “I’ve opened the bowl, gone home and fed horses, and come back and closed the bowl. So it was a lot of days of that. I do not do that anymore.”

After taking “the bowl,” as she calls it, into her own hands, Brannian thought maybe she could make more money keeping the doors open (or at least more money than teaching horse riding lessons). Brannian received help from the owners of Ferndale’s Mt. Baker Lanes, who let her borrow equipment.

“There’s a reason this place came back into my life, and I think today that’s pretty apparent,” Brannian said. “The sense of community that we have here is really special.”

Both 20th Century’s owner and leaguers compare the bowl to the show “Cheers,” where everyone knows your name and your order.

Now, more than two decades later, Brannian still owns the land, the building and the parking lot across from it on State Street. So why are so many other bowling centers closing, especially in bigger cities like Seattle?

Brannian’s answer is simple: real estate.

“Most of these centers have been built on the outskirts of town, and towns get bigger. And the real estate becomes more valuable than the business,” Brannian said. “Sad to say, that’s what will happen here, eventually, because the real estate is worth more than the business could generate.”

Fortunately for the bowling community, Brannian said, she makes just enough money to pay her workers, keep it going, and of course, feed her five horses — her true passion. And some essential workers are few and far between, specifically mechanics knowledgeable enough to maintain the pinsetters, which her father installed in the 1960s.

“If John (the primary mechanic) ever tries to leave us again, I’ve told him I will find him and chain him up in the basement. Because we would be screwed,” Brannian said. “I really think that when you see a new bowling center be built, it’ll be string pins.”

Reviving the sport and what the future holds

Whatcom County is home to three centers: 20th Century in downtown Bellingham, Park Bowl on the Guide Meridian and Mt. Baker Lanes in Ferndale. Within driving distance, Whatcom County bowlers have Riverside Lanes in Mount Vernon, Sedro10 Entertainment in Sedro-Woolley, Oak Bowl in Oak Harbor and Strikerz Bowling at Angel of the Winds Casino Resort in Arlington.

With a population of nearly 230,000, Whatcom County has more than twice as many bowling alleys per capita than the city of Seattle. And, while there were about 12,000 bowling centers in the United States in the ’60s, that number has dropped to 3,001 in 2023.

The pandemic, of course, impacted bowling alleys as it did every other business and industry. But bowling center owners were faced with harsher restrictions as Gov. Jay Inslee pushed them to “Phase 4” of Washington state’s COVID-19 shutdown.

In Whatcom County, bowling alley owners and customers rallied together outside Park Bowl during the pandemic to protest the extended closure. Indoor bowling, protesters said, allowed for social distancing and masking just like restaurants and other indoor activities opening up in earlier phases.

When bowling alleys finally reopened, Thompson said “it was like coming home.” She could finally hug people — people she hadn’t seen, at that point, in two years.

Up in Ferndale, Jason Beecroft — an avid Mt. Baker Lanes bowler — said when the shutdown happened, it broke his heart. It was scary to see alleys close, he said. Beecroft battled the shutdown by organizing folks on Facebook to buy to-go food and drinks from Mt. Baker Lanes, gather in the parking lot and socialize.

“You’re taking my family away,” he said of the closure. Soon he started buying gift cards from the Ferndale center to help keep it open.

“It’s a tough business,” Beecroft said. “I would never own a bowling alley.”

Beecroft has worked with the junior program since 2017 at Mt. Baker Lanes, which he said is a good, clean environment for kids.

“Junior bowlers,” Beecroft said, “are the bloodline of bowling. They are the future, they are everything.”

One of the many junior bowlers Beecroft works with is 15-year-old Madison McFadden, who bowls league at Mt. Baker Lanes and on Ferndale High School’s bowling team.

Last year, the team had five members — the minimum number you need to be a team. If someone couldn’t make it, McFadden said, the team was required to forfeit.

“It’s honestly kind of sad because … everybody at my school doesn’t really consider it a sport because it doesn’t have the physical demands that football would,” she said. “It’s inside, anybody can do it and it kind of gets left behind.”

McFadden said Ferndale’s team doesn’t get the funding it needs to improve. The shirts they wear are from a decade ago and aren’t even the school’s current colors. Though the team’s members fundraise themselves, like other athletes, they never end up with enough money with only five people selling chocolate bars.

“It doesn’t seem fair,” McFadden said.

Despite the small team and perception of her peers, she has made good friends and enjoys the competitive environment, especially when they travel to tournaments. Leagues and tournaments for youth bowlers, McFadden said, are key to the future of the sport.

“If we want to keep bowling going, you have to get the youth involved,” she said. “You can’t just leave it up to the adults.”

Part 1: Bowlers keep league culture alive in 21st-century alleys

Part 2: Elite female bowlers set high standards, drive change in Whatcom County