In the aftermath of the catastrophic Lahaina fire, Hawaii officials warn it’s a wake-up call for a changing world.

Aided by howling winds, low humidity and drought, the fire destroyed 80% of the city and the death toll is still climbing.

Scrutiny of Lahaina’s system response has uncovered lax emergency coordination, and poor planning for water resources, evacuations, and public warnings.

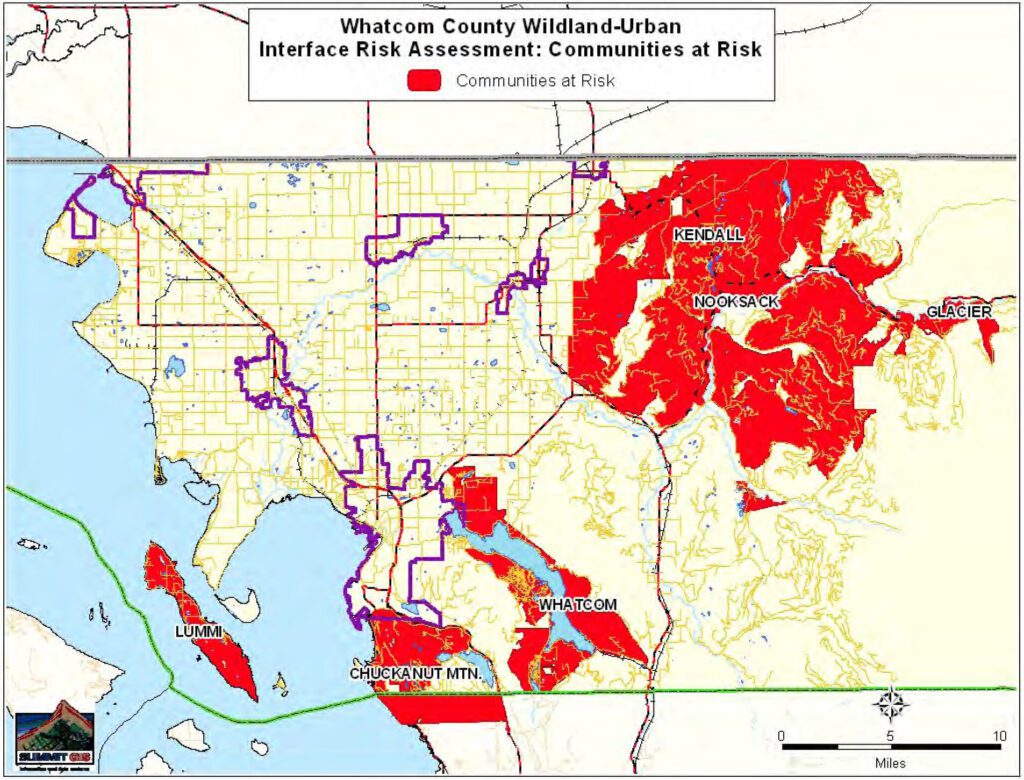

Whatcom County might seem a world away, but in wildfire terms, Lahaina is in some ways comparable to local communities surrounded by forests. Like Lummi Island and Kendall, Lahaina butts up against wildlands that have become increasingly susceptible to fire.

New research from the Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington in Seattle suggests that the western part of the state is entering a new regime, where it will start looking more like Eastern Washington: smaller, more frequent fires that rely less on a strong wind and more on heat and dryness.

Could a tragedy on the scale of Lahaina — or last week’s fires around Lake Okanagan in British Columbia, which charred about 200 structures — happen here? And are officials ready with proactive measures?

Some counties are more prepared than others.

A Cascadia Daily News review of local policies and emergency plans revealed Whatcom County has no Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP) and is only in the beginning stages of what could be at least a two-year development process. The county also will soon add a new alert system.

By comparison, Skagit County has had a plan since 2009 and updated it in 2019.

“There’s no question that our emergency response planners will take a look at what happened in Lahaina and see what lessons there are for our community,” said Jed Holmes, Whatcom County Executive Satpal Sidhu’s public information officer. “There is definitely value in revisiting our plans to see how well-suited they are for a fast-moving firestorm like the one seen on Maui.”

Prolonged drought, limited water, and finite resources, especially in more rural areas, have heightened concerns for fire response and vulnerable communities across Western Washington, including Whatcom County.

The highest-risk communities include Kendall, Glacier, Chuckanut Mountain and Lummi Island. The greatest risk, in terms of population density and property value, might be in the heavily wooded residential areas surrounding Lake Whatcom, according to the county’s 2021 Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan.

Local emergency planners cited a number of deadly fires in recent years along the so-called wildland-urban interface, including the 2020 Almeda Fire in southern Oregon, which destroyed more than 2,600 buildings and left three dead; and the Tubbs Fire in 2017, which consumed about 5,500 structures in and around Santa Rosa, California, killing 22.

John Gargett, deputy director of the Whatcom County Sheriff’s Office Division of Emergency Management, said his division ranks wildfire as the third most serious risk in the county, in terms of severity and probability, behind earthquakes and floods.

“While it is unlikely that we would see the level of damage seen in Maui, Almeda or Santa Rosa, it is possible that we could have up to a couple hundred homes affected by a wildfire,” Gargett said.

Assessing the risk

Firefighters were stymied in their efforts to battle the Almeda Fire because hydrants kept running out of water. The same thing could happen in smaller communities in Whatcom County, Gargett said.

“In some areas, even though there are hydrants, the capacity of the system is designed to provide water for two or three fires,” Gargett said. “A large event such as [what] occurred in Almeda would be problematic.”

Consider Kendall and Peaceful Valley, a pocket of residences and businesses in a heavily forested area in the Cascade foothills, about 25 miles northeast of Bellingham. Working with the state Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Emergency Management has assessed this community’s fire risk.

The area includes some 1,280 buildings and a population of 1,000 during the day and 2,800 at night.

“Their weather conditions of concern are late summer/early fall where we are in drought conditions, low humidity and northeast winds of 25–30 mph with higher gusts occurring for 12 or more hours,” Gargett said.

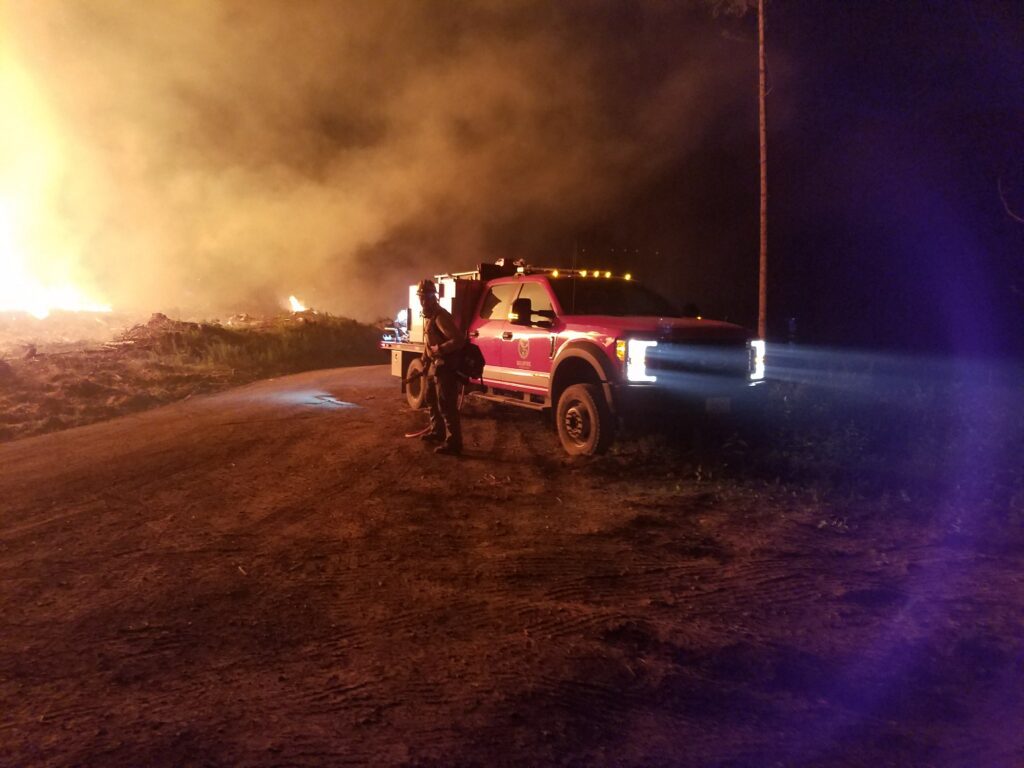

If a fire starts near Kendall, the first response would come from Fire District 14, which has three career firefighters and 65 volunteers. The district also has five water tanker trucks, four standard fire engines and three brush trucks, designed specifically to fight wildland fires.

In Kendall or Peaceful Valley, DNR fire crews would respond with Fire District 14. If needed, a state-level response would be mobilized to bring in crews from other jurisdictions.

“Based on the last five years of fires on both sides of the state, adequate fire resources have been able to be brought to bear,” Gargett said. “This does not mean that structures would not be lost, but the exact number would most likely be lower than the maximum potential.”

Fire District 14 Assistant Chief David Moe said DNR has had “exponential growth” in its wildfire fighting capability.

“Where a few years ago, we would respond to most small wildfires on our own, never seeing a DNR engine, now most of our wildland incidents have one or two DNR engines, a supervisor and a helicopter … in addition to our units,” Moe said.

Expect more Western Washington fires

Western Washington’s dense, wet forests are often perceived as immune to wildfire.

“There is still kind of the thought, ‘We’re in Western Washington. It’s wet. It won’t burn,’” said Amanda Knauf, Whatcom Conservation District’s wildfire resilience specialist.

“Folks from California or the Southwest, I think they see Western Washington a little differently than people who have lived here for a long time,” Knauf said.

Western Washington forests do in fact burn and have for centuries, well before humans started burning fossil fuels and changing the climate. Parts of Western Washington, including Whatcom County, are naturally prone to large, intense fires that flare up once every few centuries, driven by hot, dry winds out of the east.

Until recently, the largest wildfire in the state’s recorded history was the Yacolt Burn of 1902, on the west slopes of the South Cascades, just north of the Columbia River. The blaze consumed nearly 240,000 acres of forest in three days and killed 38 people.

As climate change makes its presence felt, the risk of Western Washington wildfires is increasing, scientists say, and they expect more frequent fires west of the Cascades that burn less than 25,000 acres.

“The last couple of — almost three — decades, there’s been drier summers than further back in the past,” state climatologist Nick Bond said. “We may already be feeling climate change, in terms of our precipitation.”

“The heatwave of 2021 showed how hot it can get here,” Bond added. “It’s not just an east-of-the-Cascades problem.”

Climate models also predict warmer, drier Septembers in Western Washington, which could increase fire risk at the end of the summer. The 2022 Bolt Creek Fire, which burned more than 14,000 acres of forest north of Highway 2 and west of Skykomish, King County, started on Sept. 10 during the hottest July-to-September on record, The Seattle Times reported.

“That was a good example of what we’re going to be seeing more of,” Bond said. “What was so unusual about that summer, in general, was how long it was.” Bond pointed out that Seattle reached 88 degrees one day in mid-October 2022.

Another recent example of the new fire regime might be the Sourdough Fire, now burning near Diablo Lake in eastern Whatcom County, which had grown to 6,000 acres as of Thursday, Aug. 24.

The fire is on national parkland and currently poses no risk to populated areas. Crews dug fire lines to keep the blaze out of the town of Diablo and the North Cascades Environmental Learning Center.

The next Whatcom County fire might not be so remote.

The fire in Maui ignited near Lahaina Intermediate School. The Almeda Fire started near the northern city limit of Ashland, Oregon. Strong winds carried it away from that city to the north, into the towns of Talent and Phoenix, which were mostly leveled by the blaze.

Hawaii Gov. John Green said in interviews the “fire hurricane” in Lahaina burned at “a thousand degrees, moving more than a mile a minute.”

“It was very difficult for people to escape it,” he said.

Minimizing fire risk

In Washington, efforts are ramping up to be more fire-ready. Earlier this year, the Legislature unanimously passed House Bill 1578, which requires assessments of “areas at significant risk for wildfire,” to be completed by 2027.

The assessment will expand Western Washington’s risk map and augment DNR’s Wildfire Ready Neighbors program, said Mike Faulk, deputy communications director for Gov. Jay Inslee.

“The governor understands all too well the risk to our communities created by more frequent and more intense wildfires on both sides of the Cascades,” Faulk said.

One option unavailable to most Western Washington communities is the forest thinning or controlled burning common in Eastern Washington, as a way to reduce the likelihood of a severe fire.

“Evidence shows that’s not going to be as effective on the west side,” said Crystal Raymond, climate adaptation specialist with the Climate Impacts Group. “Our forest types are so dense. There’s so much fuel, and it grows so fast.”

“Emergency response planning, evacuation — that’s really important on the west side because there is less we can do about the vegetation,” Raymond added. “So you want to think more about communication.”

The biggest challenge to a firefight in Fire District 14 would be evacuation, Moe said.

A lot of people in the Kendall area can’t drive, Moe said, and the fire district would need buses from Mount Baker School District and Whatcom Transportation Authority to move residents.

Evacuation would become even more challenging if one or more of the three routes out of the area become impassable, Moe added.

The notification to evacuate would come through the county’s AlertSense system. Residents can sign up online for email, text or voice alerts. Officials would also give notice through reverse 911 and local radio announcements, Moe said.

Whatcom County plans to implement a rapid-evacuation system within the next year, Gargett said.

What’s covered in the county fire plans

Skagit County’s 58-page Community Wildfire Protection Plan lists 15 communities that have organized to reduce their risk, in some cases through participation in the Firewise program.

Whatcom County’s CWPP, once completed, would augment the county’s Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan, which outlines how first responders would be activated in various emergency scenarios, including fires. The county is applying for grants to fund the plan process.

A CWPP identifies areas of risk and outlines measures for reducing that risk.

This plan would not be a silver bullet for eliminating the risk of fire, Holmes said.

“While a Community Wildfire Protection Plan might help draw attention to these risks, it shouldn’t be confused with an emergency management plan, which apparently is what failed in Lahaina,” he said.

In Whatcom County, five communities are active in Firewise, said Knauf, who offers free site assessments to help individuals and communities manage fire risk.

“It’s lots of little things,” Knauf said. “A lot of it is maintenance.”

This can include cleaning your deck and gutters, and keeping flammable materials such as propane or firewood away from the house.

“A lot of research has shown that if you work within the first 100 feet (of the house) to make these changes, you increase the survivability of the home,” Knauf said.

“It’s generally not the wall of flames that’s going to burn down the home. It’s the embers that fly ahead of the fire,” she added.

Knauf works all across Whatcom County — with residents of Sudden Valley, for example, or those elsewhere in the Lake Whatcom watershed who live next to properties bought by the City of Bellingham to remain as forestland.

But more work needs to be done in every community, Knauf said.

“Fire doesn’t care about property lines or neighborhoods,” she added. “The more people we can get involved in wildfire risk reduction work, the better outcomes will be if there’s a fire.”

And if a fire does come, Gargett offers some straightforward advice: “Be prepared for emergencies. You are the first responder until help can arrive.”

What you can do to reduce your wildfire risk

- Limit flammable vegetation up to 100 feet from your home.

- Remove all vegetation and material from within five feet of your house (make a gravel border, for example).

- Use Class A fire-rated roofing material, such as metal or composite shingles.

- Remove dead vegetation, debris and other flammable materials from under decks and porches.

- Make sure emergency vehicles have enough clearance to access your house. Display your street address clearly.

- Properly screen external vents to ensure embers can’t get inside or under the house.

- Make an emergency plan with family members, and know two ways out of your neighborhood. Know where you’re going to meet.

- Evacuate if you feel unsafe; don’t wait for an emergency notification.

Source: Firewise USA