Editor’s note: Due to broad public interest in this subject, this story, originally published Jan. 15, 2023, has been made available outside the newspaper’s paywall as a public service by Cascadia Daily News.

CONCRETE — David Babcock’s family is convinced he didn’t have to die at the hands of police.

An officer rapidly fired nine bullets at Babcock’s car last February after he drove over the curb on a Sedro-Woolley road to avoid spike strips. One of the bullets struck Babcock, 51, in the back of the head.

Sedro-Woolley officer Max Rosser was cleared of wrongdoing. He was briefly in the vehicle’s path, standing in the dark next to North Fruitdale Road, when he decided to pull the trigger. The Skagit County prosecutor in September determined the shooting was justified and did not press charges. The young officer, who had graduated at the top of his academy class one year earlier, returned to his job in November.

Babcock’s family plans to file a court claim this month saying police used excessive force on the night of Feb. 16, 2022, after a lengthy chase that resulted in Babcock’s death, attorney Melanie Nguyen told Cascadia Daily News. She said the claim will give the cities of Sedro-Woolley and Mount Vernon, and the Skagit County Sheriff’s Office, 60 days to settle before they are sued in federal court.

Nguyen, an attorney for Babcock’s widow, Regina, said in an interview the way police handled Babcock’s alleged crimes — eluding police and driving with stolen plates — was “an egregious, disproportionate response.”

After initial suspicion of a car being driven with a stolen plate, law enforcement officers from the three jurisdictions chased Babcock more than 20 miles that night on a winding route from the Mount Vernon Safeway via Interstate 5 to Burlington’s side streets, then past potato farms and along winding rural roads that lead to Sedro-Woolley.

Ultimately, Rosser and Sedro-Woolley police Sgt. Paul Eaton got ahead of Babcock and laid spike strips at the corner of North Fruitdale and McGarigle roads. In an effort to avoid the spikes, deployed to deflate his tires, Babcock jumped his Pathfinder onto the sidewalk and into the grass west of Fruitdale Road, where Eaton and Rosser were standing.

“It was very apparent he saw us and was trying to avoid the spike strips and get around us,” Eaton told the interagency team that investigated Babcock’s death, according to the team’s 308-page report. “And I really thought he was going to run Rosser over.”

The Skagit and Island County Multiple Agency Response Team (SMART), led by Mount Vernon police, investigated Rosser’s actions that night to avoid conflicts of interest, as required by state code.

Moments after Rosser fired into the Pathfinder, the vehicle came to a halt against a power pole along McGarigle Road. Eaton pulled Babcock out of the car and applied pressure to a wound near the back of his neck.

After reaching the scene, Skagit sheriff’s deputy Shawnn Vincent stepped in for Sgt. Eaton, keeping pressure on the back of Babcock’s head to staunch the bleeding.

“He was saying, ‘I want a cigarette. Call my wife,’” Vincent told SMART investigators.

Vincent told Babcock he was under arrest.

Hours later, after Babcock had been flown to PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, an emergency room nurse told officers Babcock wouldn’t survive.

Regina Babcock and David’s daughters, Elizabeth Babcock and Alyshia Losey, weren’t prepared for what they saw at the hospital.

“We were kind of like, ‘No, he’s just probably just in a coma, you know? He’s gonna snap out of it,’” Regina said during an interview earlier this month at her Concrete home.

“When we came into the hospital room, I know he was gone,” Regina recalled, in tears. “You can tell his soul was not there anymore.”

The investigation

Rosser was placed on paid administrative leave while the SMART team investigated Babcock’s death.

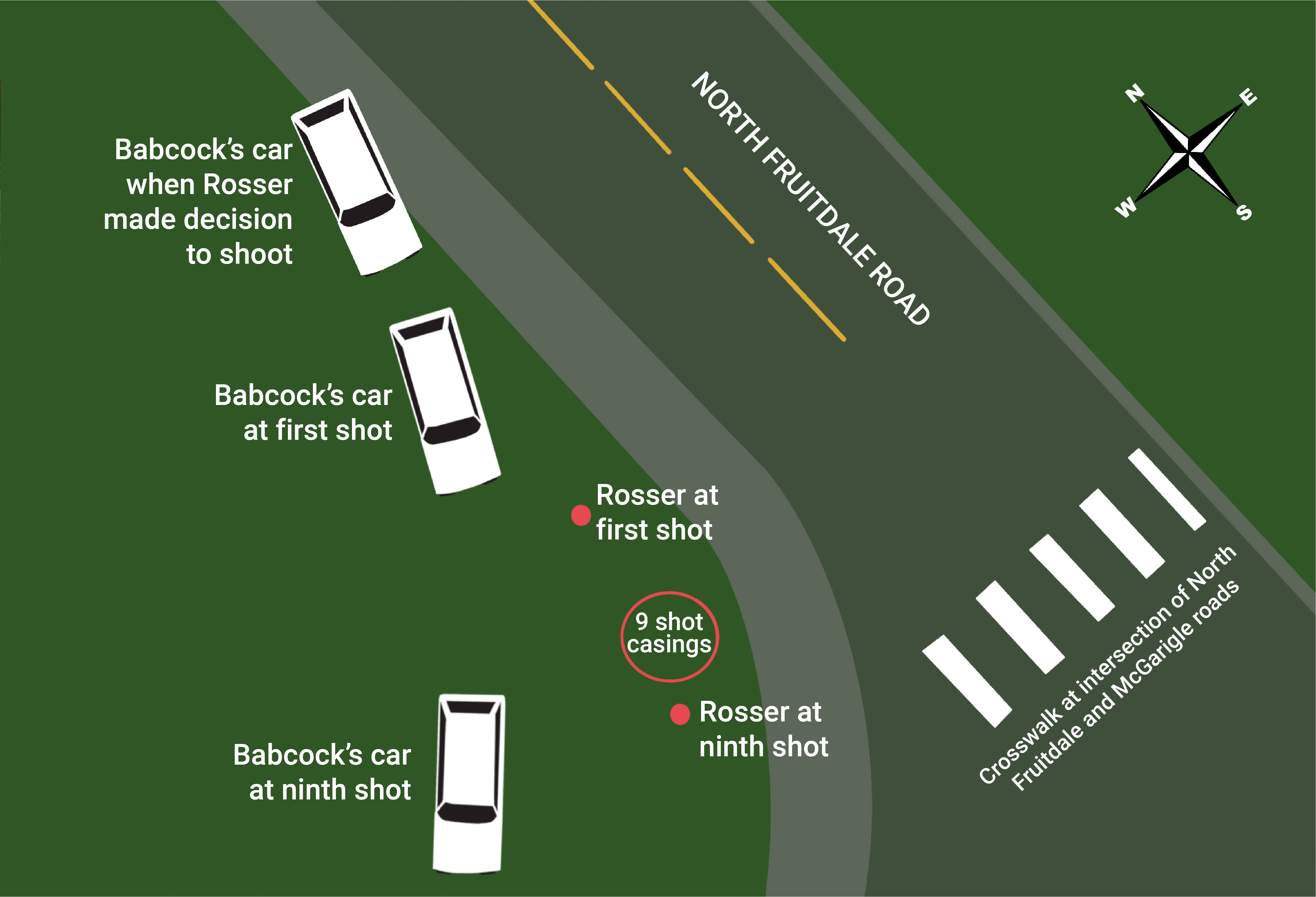

Although police were engaged with Babcock for more than half an hour before the shooting on Feb. 16, 2022, the SMART report focused on the two seconds when Rosser fired nine bullets at Babcock as he drove by the officer in the grass off North Fruitdale Road.

The report accounted for why the fatal bullet might have struck Babcock after he had already passed by Rosser, when the officer was out of danger. The SMART team’s analysis factored in human reaction time.

It takes 1.5 seconds for the average person to go from making a decision to acting on that decision, the report said. For a younger, highly trained individual such as Rosser, response time is perhaps one second. Sgt. Eaton’s body camera showed that one second before Rosser stopped firing, Babcock’s vehicle, traveling at 12 mph, was still in front of him, and Rosser stood away from Babcock’s path.

During that final second, Rosser continued tracking the Pathfinder with his service pistol, firing four more bullets. Given its trajectory into the back of Babcock’s skull, the fatal bullet likely struck him after Rosser had decided to stop shooting.

“This was our best attempt to recreate a tense, rapidly evolving situation that lasted only 2.0 seconds,” the report concluded.

The SMART team, which included forensic crime experts from the Washington State Patrol and numerous local law enforcement agencies, also determined that Babcock’s Pathfinder mirrored Rosser’s movements after jumping the curb: As the officer moved east, toward the road, the Pathfinder also veered slightly to the east. Then as Rosser moved west, into the grass, the Pathfinder turned in that direction, aiming for a narrow area between a power pole and a stormwater pond — Babcock’s only means of evasion given the spike strips laying on North Fruitdale Road.

“Any reasonable person driving the suspect vehicle would be able to see that at least two uniformed police officers were directly in their travel path,” Rosser wrote in a written statement his attorney provided to investigators more than a month after the shooting. (The SMART report does not include a direct interview with Rosser.) “Further, it was clear to me that the person driving was trying to hit me and/or Sgt. Eaton with the vehicle.”

The Babcock family’s attorney saw it differently.

“They tracked David … then stood in front of his only direction to leave and then shot and killed him — which to us is an egregious, disproportionate response,” Nguyen said.

Regina Babcock was also incredulous.

“He was driving 12 miles an hour, but that’s aiming at the officers?” she said.

A new state law passed in 2021 says an officer may not fire a weapon at a moving vehicle, “… which is not considered a deadly weapon unless the operator is using the vehicle as a deadly weapon and no other reasonable means to avoid potential serious harm are immediately available to the officer.”

After reviewing the SMART report, Skagit County Prosecutor Rich Weyrich decided not to charge Rosser with a crime, calling his use of force “justifiable.”

“Based on the science regarding perception response time, I believe Officer Rosser’s decision to shoot was a direct reaction to the vehicle coming straight at him, and that his firearm tracked that deadly threat as he fired his weapon,” Weyrich said in a five-page statement from Sept. 20.

On Nov. 22, Sedro-Woolley police issued a brief statement saying Rosser was back on the job.

“The city concluded that the shooting was justified,” the statement said. “Officer Rosser has been removed from paid administrative leave and has returned to work.”

Dan McIlraith, who became Sedro-Woolley’s new police chief in June — nearly four months after the Babcock shooting — declined an interview request.

Chief McIlraith didn’t respond to emailed questions about whether officer Rosser had followed department policy on use of force or vehicle pursuits. Officials at the Skagit County Sheriff’s Office declined to answer questions about whether deputy Vincent’s actions were in line with policy.

When the SMART team released its report in August, Sedro-Woolley announced it was making wholesale changes to its police policies and reviewing the policies in effect when Babcock was shot. The city’s statement said its “improvement” to police practices was happening “independent of this incident,” referring to Babcock’s death.

Not a pursuit?

Sedro-Woolley’s policies on pursuit and emergency driving in February 2022 made no mention of merely following a suspect — what Rosser and others referred to as “follow at a distance” — as opposed to pursuing them with lights and sirens on.

In their statements to SMART investigators, officers emphasized they weren’t engaged in a pursuit. For most of the circuitous route Babcock took from Interstate 5 to Sedro-Woolley on Feb. 16, officers lurked 100 to 200 yards, and sometimes up to a quarter-mile, behind his Pathfinder.

“I just kind of stayed back,” Deputy Vincent told an investigator. “At no time, like I said, no lights, siren, anything like that — just kind of slow, follow within speed limits, maybe accelerated a few times just to catch up to it.”

The distinction between pursuit and following at a distance is important. In 2021, the Washington state Legislature clamped down on police pursuits, allowing them only in limited cases. The new law says pursuits are limited to when officers suspect a driver is under the influence or when they have probable cause to suspect a violent offense, a sex offense or an escape from jail or prison.

Babcock’s recent criminal record included at least eight cases when he eluded police pursuit. He also resisted arrest at least once, and he fled the scene of an accident. In one case of suspected eluding, just 12 days before Babcock was shot, Rosser was the officer on the scene who identified Babcock, “based on previous interactions,” the SMART report said.

He did not meet the standard of the state’s restrictive pursuit law.

Even though officers were careful to explain to investigators that they weren’t pursuing Babcock, they did use one standard pursuit tactic in their arsenal: tire deflation devices, more commonly called spike strips.

This decision proved fatal for Babcock.

Sgt. Eaton justified the use of spike strips in his interview with investigators. He lapsed into using the word “pursuit” as he described the incident.

“This vehicle specifically has been involved in a pursuit with just about every agency in the county, and I know, at least with us I think, this will be the third pursuit we’ve had with it where he drives super recklessly,” the transcript of Eaton’s interview said. “So the concern was trying to get him to stop in a safe location at a good time.”

“I put on the radio that we could try to stop, that we could try to spike it, but we’re not going to pursue it after the fact,” Eaton continued. “If he stops, great. If he doesn’t then he’s going to at least drive on (flat) tires and be done trying to elude the police.”

Policy in place in Sedro-Woolley during the Babcock chase stated that officers should take care to deploy spike strips “from a position of safety.”

“The spike strip should not be used in locations where specific geographic configurations increase the risk of injuries to the operator, violator or the public,” the policy stated.

If the Sedro-Woolley Police Department resented the new pursuit law, then that attitude came from the top.

Lin Tucker, Sedro-Woolley’s police chief at the time, posted a self-described “venting session” on Facebook 13 days before one of his officers killed Babcock.

“I just left the scene of an incident where a suspect backed into one of our officer’s patrol cars, then rammed into two parked cars and a building before fleeing,” Tucker wrote on Feb. 3, 2022. “Fortunately, no one was hurt … and we are prohibited from pursuing.”

The Facebook post did not mention Babcock or indicate he was involved in any of the incidents that Tucker cited.

“We started seeing increased criminal activity and have since been dealing with emboldened criminals that know that we are hindered by these mandates, since those laws were enacted,” Tucker continued. He went on to urge legislators “to fix their mistakes.”

“Good luck Washington,” Tucker concluded. “You deserve better.”

In the current state legislative session, one House bill and bills 5034 and 5352 under consideration in the Senate would loosen restrictions on police pursuits.

Known to police

Officers following the Pathfinder may have suspected Babcock was behind the wheel.

Babcock’s fatal night began when a Mount Vernon officer started pursuing the Pathfinder on I-5 at College Way after running its license plates and discovering they didn’t match the vehicle. Mount Vernon police had contacted him just nine days before with the same car.

Mount Vernon wasn’t the only agency familiar with the white Pathfinder. Eaton said as much when he justified to investigators his decision to deploy spike strips. Rosser also reported being familiar with the SUV.

“I recognized this was the same vehicle that had eluded the Sedro-Woolley Police Department before and recognized it from an email from the Mount Vernon Police Department regarding an eluding they had a previous night,” Rosser wrote.

Deputy Vincent told SMART investigators that during the chase, Sgt. Eaton reported over the police radio that he thought he might know who the driver was.

“He thought he might’ve recognized him, but he wasn’t 100 percent certain, so we just continued to follow,” Vincent said.

“He turned his face, but I could see what looked like a big earring or something shiny on his left ear as he turned his head,” Eaton told the SMART team.

Police officials maintain that no one had identified Babcock on the night of Feb. 16 until they peered inside his car at North Fruitdale and McGarigle roads and found him mortally wounded.

As soon as Sedro-Woolley officers got a look inside Babcock’s vehicle, they knew who it was, even though the driver’s upper body was slumped across the passenger seat of the vehicle.

“That’s David Babcock,” one of them can be heard saying on body cam footage.

In an email interview, Mount Vernon Lt. Mike Moore of the SMART team said this explains why officers didn’t break off the chase and arrest Babcock the next day at a known address.

“Officers were unable to establish the identity of the driver prior to the deadly force incident,” Moore said.

Members of the Babcock family and their attorney said they simply don’t believe the police narrative suggesting officers didn’t know who was behind the wheel of the Pathfinder.

“I don’t believe for one minute that they did not know who was in that car,” Regina Babcock said.

“Nobody deserves that,” she added. “The cops, you know, they wanted to make sure they got him some kind of way.”

“That department had a history with David, and they did not like him,” Nguyen said. “I see no reason why they would chase a vehicle across three cities for ‘report of a stolen vehicle.’ … They never provided evidence of a stolen vehicle.”

Strictly speaking, police only confirmed that the Pathfinder’s license plate didn’t match the vehicle. The plate was registered to a Ford Ranger belonging to the Skagit County town of Hamilton. Police ended up returning the Pathfinder to Regina, who had claimed all along the vehicle belonged to her.

Regina got rid of the SUV she said David had purchased for her birthday. It was riddled with bullet holes, and the family said police had left David’s blood on the passenger seat.

Grieving family

Was David Babcock trying to strike Officer Rosser with his vehicle when he jumped the curb? The only person who can answer that question with certainty is no longer alive.

However, if he was going to successfully evade police as he drove on the grass at the corner of McGarigle and Fruitdale roads, he needed to thread a narrow path between a power pole and a stormwater pond. Rosser was standing close to that path.

Members of Babcock’s family insisted he didn’t want to harm anyone that night.

David Babcock moved to Sedro-Woolley with his wife Regina 24 years ago because his brother lived there, and they always enjoyed visiting the community. David worked at a sawmill and in construction, Regina said.

Now, he is buried next to his mother in Sedro-Woolley’s cemetery.

“Our dad is not a violent person at all,” Losey, one of David’s daughters, said. “Not even close.”

She and her sister Elizabeth Babcock recalled during the interview at Regina Babcock’s home that David even refused to spank his children.

“If you know my dad,” Losey said, speaking through her tears, “My dad’s always smiling.”

Family members recalled David Babcock as someone who loved being outdoors whenever possible, whether pulling his children on rafts behind a boat or snowboarding on Mount Baker.

“He liked adventures,” Losey said. “He never liked to just stay put.”

Elizabeth Babcock believes her father was always so intent on eluding police because he didn’t want to be separated from his family.

“That’s all our dad’s ever really done,” Elizabeth Babcock said. “He just didn’t want to go to jail. He wanted to come back to his family.”

Ralph Schwartz is a former CDN Local Government Reporter; send tips and information to newstips@cascadiadaily.com.