Editor’s note: Time to Spare: Bowling clears a lane for sport, community is a three-part series that explores league culture, highlights women bowlers, and details the impact of bowling alleys closing and the history of the sport in Whatcom County. Part two explores what it’s like to be a woman bowler through the eyes of various leaguers including Barbara Demorest, Janel Westerfield and Debbie Missiaen.

In the ’80s, Whatcom County’s elite bowling league took place at Park Bowl on the Guide Meridian. A scratch league that started at 9 p.m., it filled the whole house — 28 lanes — and, like most leagues, didn’t allow women.

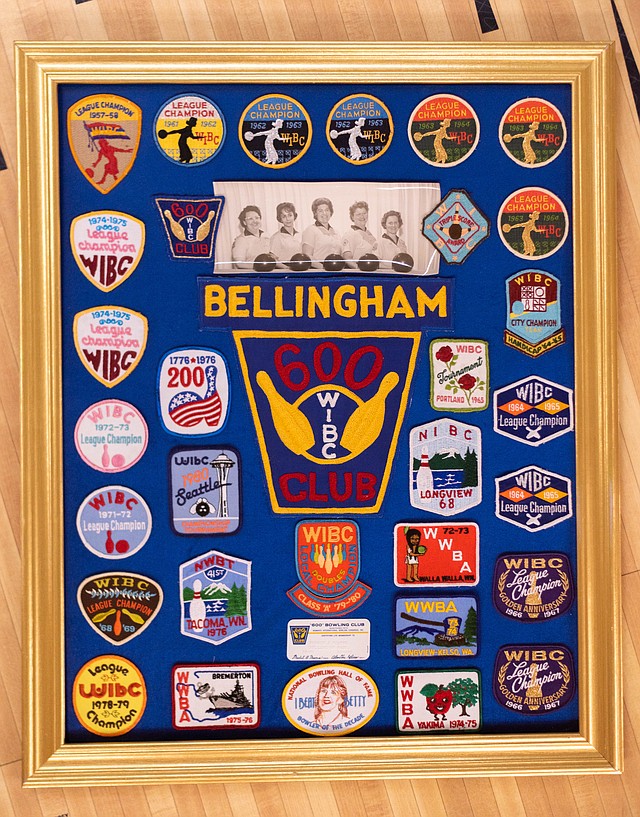

“I had the high average in the state. I was averaging 218 — I was definitely competitive for that level,” said Barbara Demorest, a Whatcom County bowler. “I thought, ‘Why can’t I bowl that league? I want to bowl it because I want to bowl with the best.’”

Demorest’s husband, Denny Demorest (a “match made in heaven” because he came from a family of bowlers) bowled the elite league and one year, decided to add her to his team. Soon after, he received phone calls from members threatening to split the league if Demorest joined.

“My husband, bless his heart, didn’t back down,” she said.

Demorest, who held the highest women’s average in the state at the time, started asking the men why they didn’t want her to join. The men were afraid they could no longer tell dirty jokes or scratch themselves in certain places, she said, and some blatantly said they didn’t want to get beat by a woman.

“You know, I heard it all,” said Demorest, now 71. “They were afraid they were going to have to clean up their behavior if women were there.”

Nonetheless, Demorest joined, and within three years, the league was 20% women.

“I did not come from a bowling family, but there was something about it,” Demorest said. “I picked up that bowling ball, and I fell in love.”

She was 13 when she got her first ball, a White Dot in her favorite color, green, which she said she treasured.

“My mom had said no respectable girl would ever go to a bowling alley. But they let me,” she said. “There’s cussing and swearing and smoking and drinking and bad language.”

When Demorest’s dad died, her mom moved here and started bowling in a league, too. Years later, her mom, 79, was in the hospital and the prognosis was not looking good.

“She looked at me and she said, ‘Barbara, do not give my league spot away. I’m gonna be back. So keep paying for a sub,’” Demorest said.

Bowling substitutes, who fill in for regular leaguers, must be United States Bowling Congress members with established averages. They don’t have to pay for the league — the missing member does instead — so being a sub is a cheap way to bowl regularly and meet new people.

When her oldest was just a baby in the early ’70s, Demorest always waited for a phone call from a leaguer looking for a sub because she couldn’t afford to bowl more than once a week.

“My kids basically grew up in a bowling alley,” she said. “I’d whip that little kid up and take him over and put him in the nursery because back then they provided free child care.”

When she wasn’t subbing, Demorest bowled a women’s league at F.erndale’s Mt. Baker Lanes. At the time, many bowling centers — including Mt Baker and Bellingham’s 20th Century — offered child care during women’s leagues, which usually took place during the day when husbands worked and wives stayed at home with the kids.

Child care, Demorest said, allowed her and other mothers to get together, “shoot the breeze” and stay active.

“I found my identity there. That’s where I found my people,” she said. “It was just a whole different circle than the rest of my world — the mom circle, the student circle, my church circle, all those circles. This was a different one. It expanded my horizons.”

As more women started working, fewer day leagues were offered — however, men’s-only leagues lived on, and some continue today. One example was 20th Century’s Merchant’s League, which didn’t allow women until the fall 2022 season.

“I wanted all my leagues to be gender fluid,” said Beth Brannian, owner of 20th Century Bowl. “Men and women compete against each other in bowling these days. So for a league to hold out and just be this boys club didn’t really appeal to me.”

Tuesdays got so small, Brannian said, that the members were told if they didn’t allow women, there wouldn’t be enough teams to fill the league.

In August 2022, they voted yes.

Lacey Thompson, a Merchant’s member, said she has experienced sexism while bowling Tuesday nights — including an opposing team member asking her male teammate, “Are your shoulders tired from carrying these girls yet?”

“You’re not going to change those minds, but you don’t have to, because … you’re getting your ass handed to you by a girl this week,” said Thompson, 37. “Is it gendered? Yes. Do I wish it weren’t? Yes. Do I think women have an equal opportunity? Yes.”

Debbie Missiaen, also a Tuesday night bowler, said men have joked they don’t want to bowl her because they’re afraid to lose. “Be nice to me,” Missiaen said she’s heard before.

Missiaen, 54, has been awarded the county’s Female Bowler of the Year four times — the first time being one of her favorite bowling memories in the 14 years she’s taken the sport seriously.

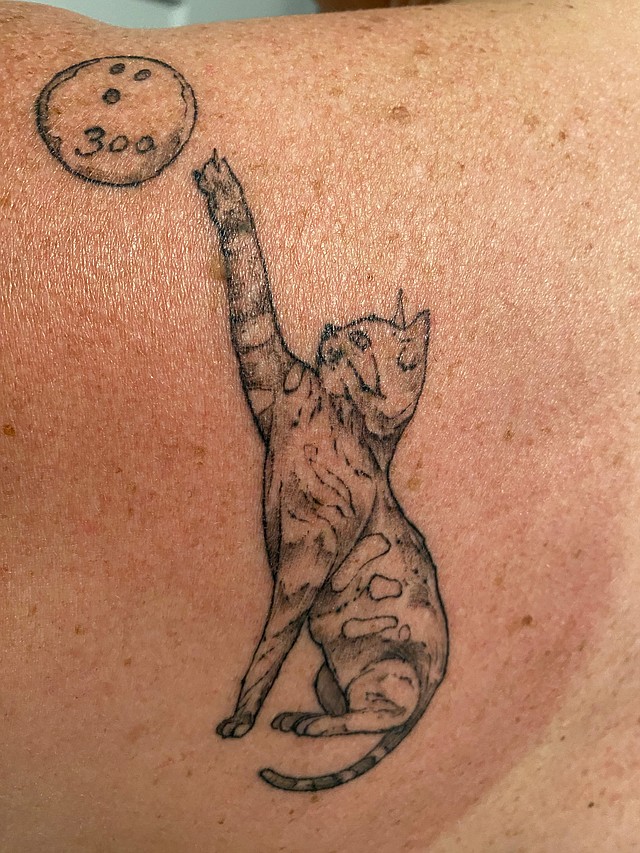

Averaging 200 or more in all four leagues she bowls, Missiaen promised herself she would get a tattoo when she rolled her first perfect game. Last year during Thursday night Social Club League at 20th Century, she finally did. The tattoo, on her shoulder, is of a cat pawing at a bowling ball that reads “300.”

“Your body has muscle memory. I firmly believe that it knows what to do,” Missiaen said. “If you can keep your head out of it, you’re fine.”

Muscle memory, however, doesn’t mean avid bowlers don’t have to think about what they’re doing with each shot. It’s a complicated game, said Demorest, who averages 191 (“that’s pretty low,” according to her) and has bowled a dozen perfect games.

In April, she reunited with two friends from her 1999 nationals team to bowl in the International Golden Ladies Classic in Las Vegas, where they played 20 games in two days. Demorest, who said she didn’t do well in the tournament, realized something halfway through the last game.

“The thought came in my head: ‘My goodness, Barb, you’re not going to cash in this event, but you’re still trying to figure it out,’” she said. “Should I use this ball? Will it hook a little earlier? Where is that oil line? It’s a very, very complicated game that you will never master, and that’s what makes it interesting. The hazards are invisible. You cannot see what’s in that ball. You cannot see that oil.”

The challenge is what some bowlers love most about it, including 26-year-old Janel Westerfield, who bowls at what is now Whatcom County’s elite league: Mt. Baker’s Wednesday night scratch.

“It’s always kind of a guessing game,” she said. “It’s always a challenge. That’s why I really like it, that’s why I keep bowling.”

Westerfield, who averages 176 and has an unfortunate high score of 299 (“I left a four-pin,” she said), believes women compensate for lower ball speeds by being more technical than men at the game.

She started bowling at 8 — where she grew up in Illinois — when her dad signed her and her brother up for a youth league. At 12, she took private lessons with a pro bowler.

Westerfield attended McKendree University, in Illinois, where she bowled on the JV team under coach Shannon O’Keefe, an 18-time member of Team USA.

“To be coached by a female was really neat,” she said.

After two years, Westerfield said bowling on an NCAA Division II team was overwhelming and she was struggling mentally.

“So I ended up quitting — and I have no regrets. After that, I lost my love for bowling,” Westerfield said.

She took a break for three years, and after moving to Bellingham in 2020 and feeling isolated during the height of the pandemic, she joined a league at Park Bowl. Her teammates, including an older couple, welcomed her with open arms.

“That opened the door to the community for me,” Westerfield said. “That’s when I started meeting more people and it really helped me get out of feeling stuck.”

She met Carl Nichols, a local pro shop owner who drills bowling balls and coaches Whatcom County bowlers. Nichols recruited her to Mt. Baker Lanes, which Westerfield said has a “family vibe” and has helped her find a love for the sport again.

A few years ago, Westerfield, a digital marketing expert, decided to test out marketing strategies on social media by creating @janelbowling, a bowling-focused TikTok account. Within a month, she gained 10,000 followers.

She tries to create relatable content for avid bowlers, preferably funny videos that follow current trends on the platform, and controversial videos about bowling etiquette that tend to stir up arguments in the comments between serious and recreational bowlers.

During league, Westerfield sets up her phone on a tripod and live streams Wednesday nights at Mt. Baker Lanes. Thanks to social media, Westerfield doesn’t think bowling is a dying sport.

“More young people are getting into bowling,” she said. “I hope my TikTok presence and my social media can encourage more females, especially younger ones, to get into bowling.”

Part three details the impact of bowling alleys closing and the history of the sport in Whatcom County.