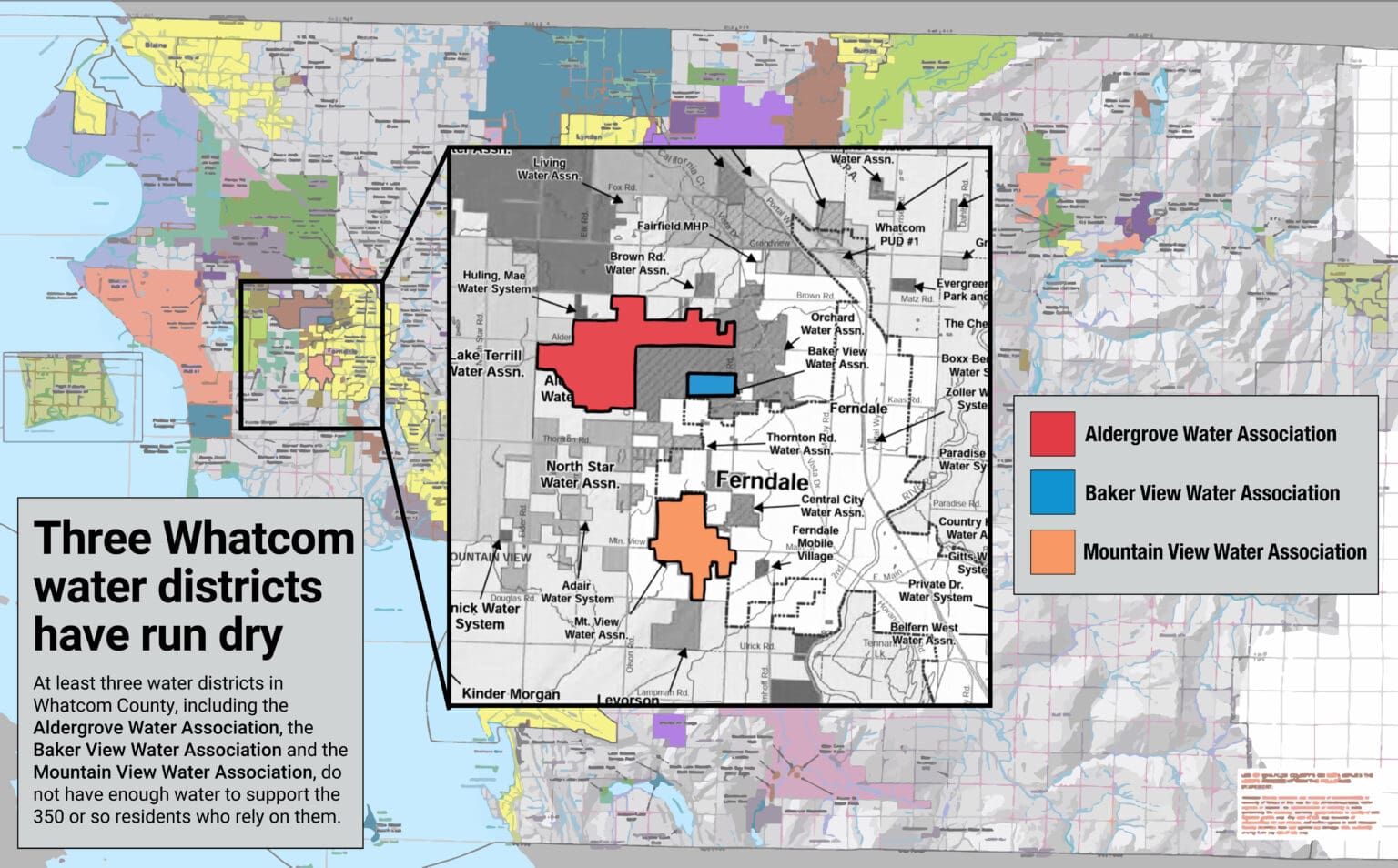

More than 300 Whatcom County residents rely on three public water systems that have run dry, and three more systems are currently “on the fringe” of emergency situations.

A public water system running dry is an anomaly, said Dave Olson, a licensed water system services operator who manages the three dry wells, as well as others in the county.

The three wells, located just outside Ferndale city limits, have left some residents with dry faucets and high water bills as the Baker View Water System, the Aldergrove Water System and the Mountain View System are forced to haul water in via truck or partner with cities for emergency resources.

“It’s not uncommon to have this happen to a private well, to have to truck in water,” Olson said, “but for a public water system like these — I’ve been doing this for 30 years, and I think I’ve only seen it one time for a system.”

Whatcom was one of 12 Washington counties named in a Monday, July 24 drought emergency declaration from the state Department of Ecology. Abnormally low rainfall, rising temperatures, early snowmelt and low streamflows have resulted in the three public water systems operating on “emergency status,” according to Ecology — meaning they’re effectively drawing air.

On Tuesday, July 25, Baker View and Aldergrove were totally out of water, or precipitously close to it, and Mountain View had opened an emergency intertie with the City of Ferndale, meaning the well system could connect to the city’s water supply.

Part of the challenge with the wells, Olson said, is that they’re relatively shallow. He said the county’s 200 water systems operate sort of like a bathtub, typically refilled each year by winter and spring rain and snow. Each well effectively acts as a straw to suck water out for personal, recreational and agricultural use. And these three straws, he explained, aren’t hitting what’s left in Whatcom’s “bathtub.”

Because of ongoing regional drought conditions, the bathtub never got a chance to refill. Earlier this week, Ecology declared a drought emergency across 12 counties, including Whatcom, where rainfall totals in some areas are just 25% of normal, according to recent data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

In Washington, droughts are declared when water supply levels are below 75% of normal and “there is a risk of undue hardship,” Ecology representatives wrote in the Monday, July 24 emergency declaration. “Watersheds that fell under this year’s drought declaration are reporting a range of hardships, including limits on water users with more junior water rights, difficulties with fish passage, and a need to truck in drinking water to residents.”

Ecology predicts hot, dry weather will continue well into October this year, meaning Whatcom’s bathtub won’t be able to refill until then, when more consistent rain returns to the region.

City of Ferndale Communications Officer Riley Sweeney said this year is markedly different from years past.

“It didn’t get this bad last summer,” he said.

At this point, at least three additional wells are rapidly approaching empty, Olson said. Residents of those areas already have had to restrict water and reduce water usage. Those three water districts are conducting monitoring and tracking water levels to ensure they don’t dry up.

“There’s only two ways you know you have a problem or you know you’re going to have one,” Olson said Tuesday. “First is, there’s no water coming through the tap. The other way is if you have relatively expensive equipment to monitor the level in the well. Some systems have that. Most don’t.”

The other three water systems, which Olson declined to identify, are currently “on the fringe” of emergency situations. One of the wells is quite shallow — just 40 feet deep, while the city of Ferndale’s main wells are both more than 150 feet deep — meaning one of the only solutions is to create another, deeper well.

In an emergency situation, like the one Ecology declared Monday, it can take just weeks to acquire permits to drill a new well in Whatcom County. Even so, the process can be expensive and out-of-reach for smaller water systems.

Generally speaking, the well-permit process requires significant research, as well as a 72-hour waiting period between filing the permit and drill work. In times of emergency, though, Ecology’s well construction coordinator for the region, Noel Philip, said they can waive the waiting period to get water to residents faster.

Other solutions, Olson said, include connecting to existing water systems through an intertie like Mountain View has, but that can be even more expensive and connection work will likely take months.

“For these three on the edge, it’s not an immediate solution,” Olson said. “If they run out of water tomorrow, [an intertie] won’t help them. They might be ready next year.”

Of the three, Olson said one is actively preparing to drill a well, while the other two are “kind of like deer in the headlights, hoping the water holds out” and still exploring alternative solutions.

Already, residents are facing higher water bills due to the emergency situation over the cost of transport. Olson called purchasing and hauling water for the wells “a far greater expense” than pumping it out of the ground.

A previous photo caption in this story misidentified three water associations as public water districts. The story was updated July 30 at 5:30 p.m. Cascadia Daily News regrets the error.