Editor’s Note: Beyond Bars: The future of justice in Whatcom County is a special report that explores the county’s controversial effort to build a new jail. Voters on recent jail bond measures made it clear they won’t accept a new jail without better social services for the people who wind up behind bars. This week, we examine possible solutions, both present and future, to “the big three” social ills. The story includes experiences of a diversion program participant, “Tony,” who agreed to share his story if he could maintain his privacy.

After a modest gathering to celebrate his 25th birthday, Tony drove back to Bellingham’s Locust Beach, where he lived out of his car.

He didn’t know where he would go the next day, or where to find food or clean clothes. Court cases and legal issues were piling up, and he didn’t know the first thing to do to address them.

It was his birthday, but Tony felt hopeless, lonely and abandoned.

“I turned off the car and just sat there for a little bit,” Tony said. “I just remember thinking, ‘I got that cake in the back.’”

Tony had been introduced earlier that day to Adam Fryer, a case manager for Whatcom County’s Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion program, or LEAD. Fryer gave Tony a chocolate cake to celebrate his birthday. It was all the food he had to eat at the time.

Tony isn’t the LEAD client’s real name. He agreed to share his story if he could maintain his privacy.

Fryer took the time to explain to Tony the services that LEAD provides.

LEAD is intended for low-level offenders such as Tony, whose behavioral health problems or unstable housing can put them in situations that get them booked into jail — where their problems only get worse.

Clients get a case manager who helps them find housing, drug treatment and a job.

LEAD may be an early model for officials who are planning a new jail for Whatcom County with an eye to reducing incarceration. LEAD and a similar county program called GRACE get people in crisis the help they need, rather than warehousing them behind bars.

Fryer helped Tony stay on top of his legal obligations, so he wouldn’t miss a court date and get into even deeper trouble. In addition, Fryer connected Tony to food banks and places where he could get clothes and gasoline vouchers.

Tony said he stopped drinking, using drugs and smoking cigarettes. He now has clean clothes and a roof over his head.

He said he also began to remember what love felt like.

“I left my house when I was 13, and I never grew out of that 13-to-16 mentality,” Tony said. “This guy is kind of taking me by the hand like a big brother … I’m thankful for that because without that, I wouldn’t have been able to do it by myself.”

Progress already

Programs like LEAD and GRACE, or Ground-level Response and Coordinated Engagement, are already part of the solution to the crises of homelessness, mental illness and substance use disorder in Whatcom County. They were also intended as a solution to high incarceration levels in the county. The two programs, along with the 32-bed crisis stabilization center opened in 2021 and renamed the Anne Deacon Center for Hope, were recommended in a report the county commissioned from the Vera Institute of Justice.

The Vera report, developed during the county’s unsuccessful campaign for a jail bond measure in 2017, outlined ways to reduce inmate numbers in the county after noting the incarceration rate had more than tripled from 1970 to 2014, even accounting for population increase.

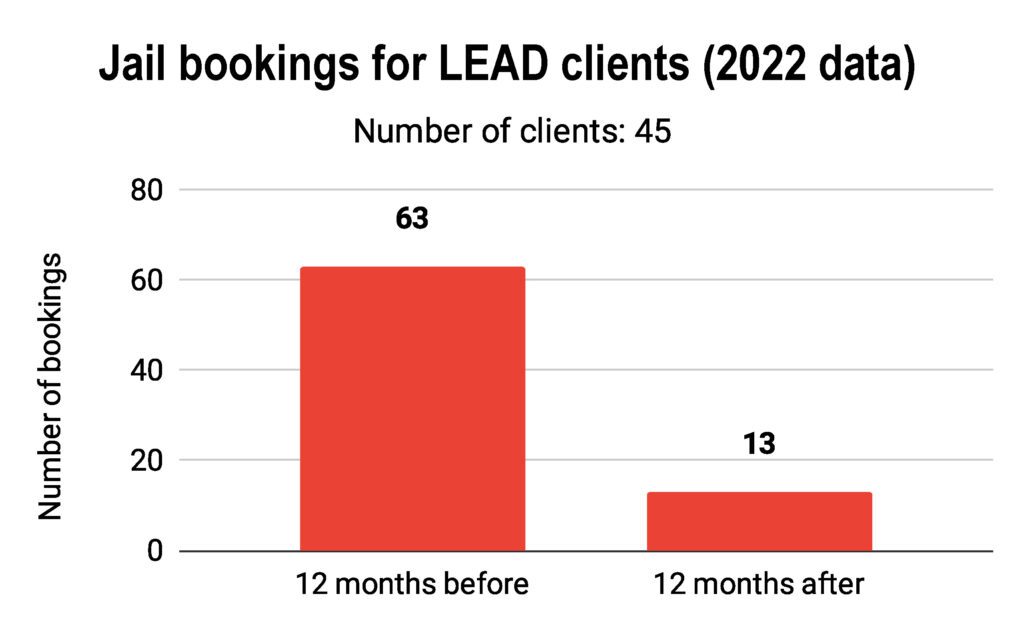

GRACE and LEAD are working, according to data from Whatcom County Health and Community Services.

LEAD is keeping people out of jail. Data collected in 2022 showed that clients spent a total of four days in jail in the 12 months after completing the program, compared to 97 days in the 12 months prior. From 2019 to 2021, GRACE and LEAD saved the county more than $8 million in jail and emergency medical services costs. The net savings is less; GRACE and LEAD have a combined annual budget of $2.59 million.

GRACE is similar to LEAD, but rather than addressing low-level offenders, GRACE takes on frequent users of emergency response and social services. A majority of GRACE clients have mental illness or substance use disorder. Most also have medical problems.

David Goldman, an educator with Whatcom Community College who taught classes to inmates in Whatcom County Jail, indicated that LEAD’s success may be due in part to buy-in from the people most affected by the program.

“The LEAD program … was really supported by the inmates,” Goldman said. “We asked the inmates, as a project in the class, for input on that. And I think that’s part of it: asking the people who are going to be impacted, the inmates, the staff of the jail and the community, ‘What do we want and need?’”

Goldman surveyed inmates more broadly last year, this time in his role as a member of the Stakeholder Advisory Committee, the 38-member panel tasked in 2022 with developing a needs assessment for a new Whatcom County jail.

One need rose to the top in Goldman’s survey: support for finding housing after jail. Of those surveyed, 43% lost housing and 35% lost their job after being jailed.

When asked what would have helped them avoid jail, the most frequent response was “a stable place to live,” at 54%, ahead of “help with mental health issues” (48%) and “drug/alcohol treatment” (41%).

“Help finding housing” also was the No. 1 community support needed to be successful once out of jail, mentioned by 76% of respondents. “Help finding a job” was second. Mental health and substance-use treatment were fourth and fifth on the list.

“If you go to jail for 90 days or less and you lose your job and house, there is no help when you are released,” one inmate wrote in the survey. “You are just left to the streets. Getting back on your feet once you are homeless with nothing is extremely difficult.”

Solutions near and far

So what should a new jail for Whatcom County look like?

County officials are looking to their immediate neighbors to the south — and a far-flung community in the southeastern United States — for recent examples of how communities solved the incarceration and social services puzzle.

When Skagit County voters approved a sales tax measure in 2013 to fund jail construction, the existing jail across the street from the courthouse in Mount Vernon had been overcrowded for more than a decade, Skagit County Sheriff’s Lt. Deanna Randall-Secrest said.

The ballot measure passed with 72% of the vote.

As in Whatcom County, Skagit residents had “a very aggressive focus” on rehabilitation instead of incarceration, Randall-Secrest said.

“The community really bought into that, and wanting that kind of environment, instead of just keeping people in and returning them back out to the community where they could continue to harm the community,” she said.

Mental health providers are available to inmates in the Skagit County Jail, as are programs in collaboration with Skagit Valley College that enable inmates to gain education and experience.

“If you try to do something and change that direction (in their lives), you’re going to help them become productive people because they’ve found out somebody cares about them,” Randall-Secrest said.

Whatcom County Council Chairman Barry Buchanan was part of a Whatcom delegation that visited the Skagit County Jail in February. While Whatcom County’s main jail is busting at the seams with some 180 inmates, the Skagit jail is half full with a population around 200.

“There’s a lot to learn there,” Buchanan said. Small design features can enhance mental well-being, including the skylights in inmates’ pods in the Skagit jail.

“It’s much better for medical and behavioral health,” Buchanan said. “It’s got a nice waiting room with a receptionist. It looks like a doctor’s office.”

Buchanan and other Whatcom officials also visited Nashville, Tennessee, in March, to observe that community’s “23-hour” urgent care center for behavioral health and a separate 60-bed behavioral care center, which is next door to the jail.

The behavioral care center is a jail alternative for people arrested on misdemeanor charges with mental illness or substance use disorder. Those who finish the program are given resources to continue their care after their release, and they have their criminal charges dropped.

Both concepts, the urgent care and behavioral care centers, could be applied here, Buchanan said. He was particularly struck by the trauma-informed design in the 60-bed center that included “tons of natural light.”

“We liked the colors, and the light everywhere, if we can do it,” Buchanan said.

But Buchanan noted that only 30 of the 60 beds in the behavioral care center were in use.

Sheriff’s officials in Nashville estimate 1,500 to 2,000 people will receive treatment at the center each year.

“We were thinking maybe we can do better there,” Buchanan said.

Next steps

After the Stakeholder Advisory Committee’s yearlong planning effort, work on a new Whatcom County jail is in the county council’s hands. The council hopes to complete its work by June, or July at the latest, in time for a jail-construction levy to appear on the November ballot.

While the SAC came up with a 110-page needs assessment for the new jail, it left many questions unanswered.

Jail planners haven’t decided on a site for the new jail, although they’ve narrowed the choices down to three: a 40-acre property in Ferndale that was the site proposed for the failed 2015 and 2017 bond measures; a 3.5-acre property in the Irongate neighborhood, near the current minimum-security jail; and somewhere on county property near the courthouse, including possibly the 1.3-acre south parking lot.

Nor have county leaders decided on the number of beds that would go into the new jail, not to mention its design or the cost of construction. Officials have mentioned a rough estimate of $150 million, but no one has done the work yet to break down the exact cost.

Also unanswered: How will mental health and substance use treatment fit into the new jail, and at what cost? How much of the jail bond proceeds can pay for emergency housing or treatment centers away from the jail?

“I think the jury’s out on that,” Buchanan said.

Tyler Schroeder, the deputy county executive, presented a good way to think about all this funding — at least for government wonks.

“I think it’ll look a lot like a six-year capital plan,” Schroeder told council members at a Feb. 7 meeting. The deputy executive was referring to a planning document that helps officials prioritize the facilities they intend to build and the programs they want to create, while at the same time figuring out where all the money is going to come from.

Schroeder also was signaling that the facilities and programs can’t be established all at once. It’s going to take six years, and likely beyond that.

If the council opts to create a 0.2% sales tax through the November ballot measure, then jail planners can figure out how much money will be left over after jail construction costs are penciled out.

Schroeder didn’t want council members to get their hopes up, however.

“The needs are probably going to be more than those funds that are available,” he said.

Additional funding could come from the state Legislature. Local legislators have already begun asking how much money the county needs to support behavioral health services, but county officials haven’t been ready with an answer because they don’t have a plan.

“We’re not limiting our resources to just a ballot initiative,” Buchanan said at the Feb. 7 meeting. “We’re looking at existing resources, potential new resources, potential legislators coming in December and saying, ‘How much money do you need?’”

“Maybe we’ll know this time.”

A previous version of this story incorrectly described data on jail time for participants in the LEAD program. The data included days spent in jail after completing the LEAD program, not after starting it. The Cascadia Daily News regrets the error.

Ralph Schwartz is a former CDN Local Government Reporter; send tips and information to newstips@cascadiadaily.com.