ARCTIC NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE — Silver clouds speckle the denim blue sky as the sun peeks out from behind a mountain. Spotlights of orange hues hit the rigid peaks as a dusting of fog settles atop the lake.

I look at my watch: 2:34 a.m. The sun tracks the horizon line, but never falls below it. I stay up all night, riding the everlasting peak of sunset, enthralled by the land shimmering in the midnight sun.

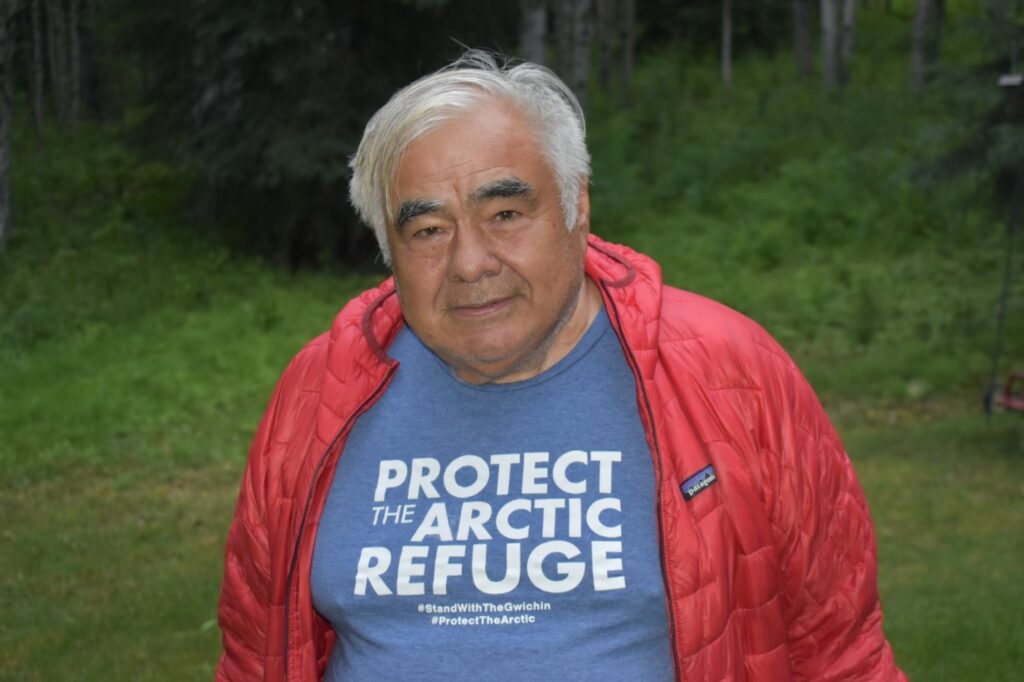

I’m here in the heart of the Arctic Refuge along with eight other activists at the invitation of Robert Thompson, an Iñupiaq elder and ardent defender of this land, which is considered sacred to both the Gwich’in and Iñupiat peoples. Occupying the entire northeast corner of Alaska, the Refuge’s 19.6 million acres comprise one of the most biodiverse regions left on the planet. It is also home to rich deposits of oil and gas.

The decades-long debate around the Arctic Refuge has become a symbol for something beyond simply drilling for oil. It’s about climate change, preserving wildlife, honoring culture, acknowledging history, and the well-being of our collective future.

“We who live here are aware of the impacts [of climate change] on the land,” Thompson said. “People in the cities don’t realize some of the things happening here. I can’t emphasize enough how serious it is.”

On Sept. 6, the Biden administration took a major step toward permanently protecting the Arctic Refuge by canceling all remaining oil and gas leases issued under the previous administration. The cancellation of the leases only comes because of the work of people like Thompson.

I met Thompson three years ago over a cup of coffee in Fairbanks, Alaska. His wisdom, passion and humor struck me immediately. He believes that the more people who learn about the Arctic Refuge, or visit it themselves, the more people will join the fight to protect it.

Years in the making, my own expedition starts in Arctic Village, Alaska, where I hop in the front seat of the 1975 Cessna A185F seaplane named Elcy and feel a rush of nerves as the engine starts up. The plane’s third-generation pilot, Danielle Tirrell of Coyote Air, flies through the rugged and challenging environment with ease, as if her aircraft is merely an extension of her body.

We circumnavigate Mount Chamberlin, the third-tallest peak in the Brooks Range, my eyes transfixed on the contours of the 1,000-year-old glacier wilting over the peak’s edge. A creek flows from the toe of the glacier, traveling from the pale limestone, through the thick brush and down into Schrader and Peters lakes.

We land so gently, we barely cause a ripple in the water and putter toward shore, where Thompson stands waving.

“So,” Thompson asks, laughing as he already knows the answer to the question he is about to ask. “What do you think?”

It feels like I am in a painting. The mountains explode with grace out of the pastel-colored tundra floor; wildflowers dot the land in pink, violet and ivory speckles; the landscape looks soft as velvet. This kind of beauty feels foreign, pure and raw.

As the Arctic warms two times faster than the rest of the planet, Thompson sees the impacts of climate change firsthand. Starving polar bears dumpster dive in Kaktovik, the village he calls home; the numbers of Dall sheep and muskox are in decline, and melting permafrost erodes the shoreline. The Arctic is already in danger. Drilling in this delicate ecosystem would only expedite the devastating impacts.

Thompson and I sit at the shore of the lake drinking coffee for hours, maybe even days, it’s hard to tell when the sun never sets. He tells me about all the climate conferences he is attending throughout the rest of the year, the op-eds he plans to write on the Arctic, the hunting trips he has planned for the winter.

As he speaks to me the sun illuminates him like a spotlight. His hands, calloused from years of Arctic raft guiding, wood carving and caribou hunting, fidget in his lap as he speaks. He mirrors the land surrounding us.

Over the next eight 24-hour time periods we do away with the constructs of day and night. We tune into the land and sleep when it rains, when the mosquitos get too bad or simply when there is a lull in conversation.

We fly fish, eating only fresh arctic char and lake trout garnished with the native plant bistort, whose stem tastes like snap peas. We paddle across Schrader and Peters lakes basking in the silence of being in one of the most remote places in the U.S.

We follow caribou trails up mountains adjacent to camp, discovering fresh grizzly scat, caribou jaw bones and views of the Arctic Ocean just 70 miles to the north. Most importantly we spend time connecting to the land, ourselves, and Thompson.

Thompson asks me to tell people about this place. Tell them why it is so special, why they should care and why it is so integral to our future. He also asks me to come back.

While the Biden administration is moving in the right direction, the end goal is for the entirety of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to be designated wilderness, the strongest form of land protection our government has. Thompson won’t stop the fight until it happens, and neither will I.

CDN outdoors columnist Kayla Heidenreich writes monthly, of late from Juneau and beyond; heidenreichmk@gmail.com.

Supreme Court justices make life/death decisions, but could they carry your mail?