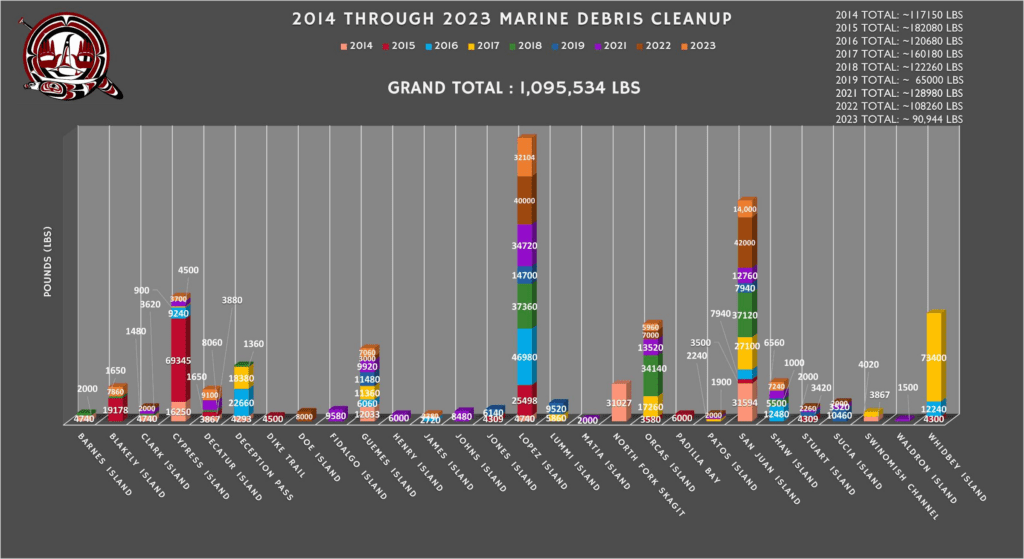

The Samish Indian Nation cleaned up more than a million pounds of marine debris — most of it highly toxic creosote-treated wood — from the shorelines and waters of Whatcom, Skagit and Island counties in the past decade.

The cleanup was done through a partnership with the Washington State Department of Natural Resources and conservation programs starting in 2014.

“Our culture is directly tied to the environment around us, and preserving the land and water of the Salish Sea honors our ancestors and future generations alike,” said Tom Wooten, chairman of the Samish Indian Nation. “The work the Samish DNR is doing preserves our cultural identity. Without the water and life within it, we have nothing.”

Marine debris, including creosote-treated wood, poses grave threats to marine life and ecosystems, disrupting food chains and harming cultural and environmental health.

The partnership brings together the state’s relatively small restoration program with the tribe, Washington Conservation Corps, Veterans Conservation Corps and EarthCorps for a summer cleanup blitz along difficult-to-access beaches in the Samish’s traditional territory.

The effort mostly targets rocky beaches cut off from land access, taking advantage of the tribe’s beach-landing vessels and favorable weather conditions during the summer months.

The tribe provides two additional boats, skilled captains and fuel to bolster state efforts, while Washington Conservation Corps crews do the literal heavy lifting of collecting, breaking down and removing marine debris.

These crews have removed styrofoam, crab pot buoys, plastics — and even entire sailboat hulls. However, the vast majority of what’s taken off the beaches is creosote-treated wood.

Creosote, also known as coal tar, has been used for more than 100 years as a wood preservative to prevent the decay of marine pilings in the Puget Sound. Though effective in protecting wood from fungi, insects and salt water, the product poses significant environmental and health concerns.

The thick, black liquid used to treat the wood contains about 300 chemicals, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons — a known carcinogen.

“Creosote is a cocktail of about 30 known carcinogens,” said Chris Robertson, the restoration program manager for the state DNR’s Aquatic Resources Division, which conducts marine debris cleanups year-round.

Placed or accumulating in nearshore habitat, creosote wood leaches toxins into fine sediments where forage fish spawn, which can cause increased mortality among their eggs and accumulation of toxins in their tissue.

“And, forage fish are one of the primary food sources for out-migrating salmon,” Robertson said.

“So, right there, you’re introducing this toxin into the food chain.”

Through bioaccumulation, those chemicals build up in a variety of animals, including salmon, killer whales and humans. Creosote contamination can be thought of as a “low resolution” chemical spill that’s eroding the baseline of the food chain in the Northwest, Robertson said.

“Every bit of creosote and other marine debris that we remove eliminates toxins from the environment that then no longer find their way into the food chain and up into salmon, up into Samish citizens or up into relatives of the J Pod,” said Todd Woodard, the executive director of infrastructure and resources for the Samish Indian Nation. “Everything we do links back to: How does that help perpetuate Samish culture for future generations?”

Residents wanting to report marine debris for removal are encouraged to do so through the MyCoast phone app. Information collected through the app “is used to characterize beach change and the impact of nearshore hazards in order to enhance awareness among decision-makers and stakeholder,” according to its website.

Since it was launched in Washington in 2018, there have been more than 9,000 reports made through the app, including nearly 14,000 images.

“The awareness that’s grown over the MyCoast App has been huge because that enlists the general population to help us locate stuff,” Woodard said, noting that through the app there’s a way for property owners to give the state permission to access their private beach.

During the spring, the Samish Tribe will survey these areas and others to help draw up a battle plan for the summer attack on marine debris, explained Matt Castle, manager of the Samish Indian Nation’s Department of Natural Resources.

The partnership between the state and the tribe has been so successful that the state DNR has emulated it with two other tribes in the region, Robertson said.

“While the world around the Samish people has changed dramatically over millennia, one thing has stayed the same: our commitment to preserving and protecting our land and waters, making it better for millennia to come,” Wooten said.

Isaac Stone Simonelli is CDN’s enterprise/investigations reporter; reach him at isaacsimonelli@cascadiadaily.com; 360-922-3090 ext. 127.