A Whatcom County resident received a suspicious message last week from a close friend residing in Russia in support of the war in Ukraine.

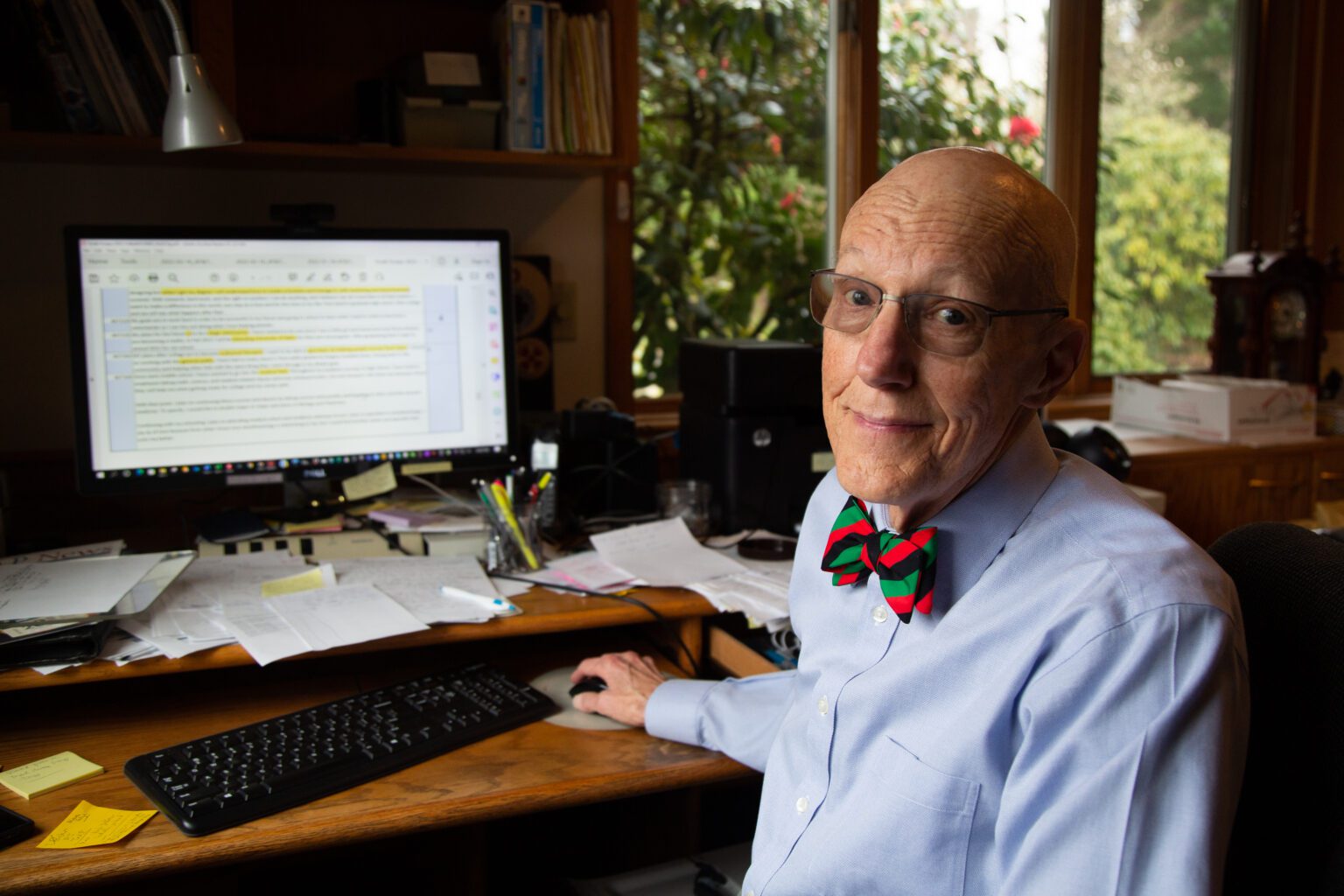

Kenneth Gass, 75, a retired Bellingham pediatrician, said he sent a short email to his friend, Michael Lazarev, who lives in Russia. In the message, Gass wished the family well and made no reference to the war in Ukraine. He received a bewildering email from his friend’s mail.ru account in reply:

“Thank you for worrying about us. We are waiting for the end of the military operation in Ukraine to stop the spread of fascism. This is a forced operation. Russia had no other choice. Everything that the American media shows about Russia is an absolute lie. That’s the kind of time we live in today. Russia will cope with all the difficulties of the economy. The main thing is to return peace to Ukraine!”

Gass knew the message couldn’t have come from his friend, who is usually warm and affectionate, he said.

“It was very formal and just went straight to the party line,” Gass said. “Putin could have written that. I said, ‘this just doesn’t seem like Michael.’”

Gass believes his initial message, sent from his Gmail account, might have been intercepted by the Russian secret service. He doesn’t think his friend ever received the email.

Propagandized messages wouldn’t be uncharacteristic for the Kremlin, which has used social media and online outlets to spread disinformation about the war in Ukraine to people in Russia, Ukraine and throughout the West. Russian groups use propaganda to divide Western forces and garner internal support for what President Vladimir Putin calls a “special military operation” in Ukraine.

An Associated Press article reported that anti-Ukrainian posts from suspicious accounts on Twitter and Facebook jumped 11,000% on Feb. 14 — 10 days before the invasion began.

“When you see an 11,000 percent increase, you know something is going on,” Dan Brahmy, CEO of Cyabra, an Israeli tech company that analyzes data for misinformation, told the AP. “No one can know who is doing this behind the scenes. We can only guess.”

Gass and Lazarev have been close friends for three decades and worked closely with one another to develop an international health program for asthmatic youth, Gass said. They are still in touch, he said, but Gass hesitates to reach out again after the recent exchange. He fears that the Russian state might be monitoring Lazarev’s communications and that further contact could endanger Lazarev and his family.

“I’m really stuck,” Gass said. “There’s no way that I can reach out to Misha (Michael) at this point for his family’s safety’s sake.”

Whatcom and Skagit counties are home to more than 6,000 people of Russian or Ukrainian descent, according to 2020 data from the American Community Survey. Nakhodka, a Pacific port city in Russia, is one of Bellingham’s sister cities, further connecting Whatcom County to the country.

Because of these close ties, Gass said, he believes other people in the community might be experiencing similar messaging and wants to bring awareness to the issue. Gass said all he can do now is hope for his friend’s safety.

“I was just heartbroken at first, and now I’m just worried,” Gass said.