On a gray mid-January Sunday, more than 100 people shuffled into the sanctuary of Clearbrook Lutheran Church. The quaint white building topped with a bell and nestled in farmland between Lynden and Sumas has stood for 120 years, serving generations of Whatcom County families.

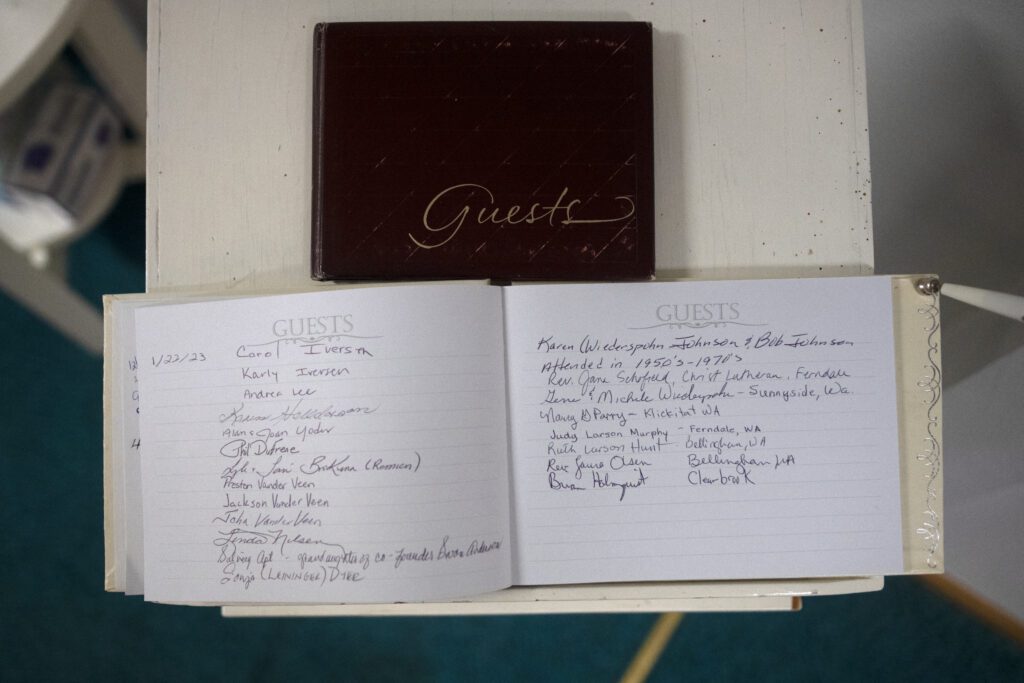

That day, Jan. 22, the pews were packed. Church assistants hurried to set up folding metal chairs in the hallway beyond the sanctuary, where an overflow of people watched the service through windows. With too few printed bulletins, parishioners shared.

The heavy attendance was a rarity — like that of a funeral, churchgoers said. In some ways, it was. Sunday marked the last service at Clearbrook, one of the 10 churches in the county that are part of the Northwest Washington Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

Despite the Jan. 22 crowd, Clearbrook was down to just five active members upon closing its doors. Rev. Marjorie Lorant, who served a neighboring Lutheran church in Lynden, delivered the last message since Clearbrook hasn’t had its own full-time pastor in decades. In the coming weeks, the fate of the church building will be determined, whether it is sold or a new ministry moves in.

“I know some of you are tremendously sad and grieving over the fact the church will no longer be here as you know it,” Lorant preached. “But you know, life changes. It’s not that you have failed. It’s not that there is something you have done wrong.”

Clearbrook could not survive a dwindling congregation, financial troubles, lack of consistent leadership and geographic isolation.

“Every church has a lifespan,” said Diane Johnson, director for Evangelical Mission of the Northwest Washington Synod.

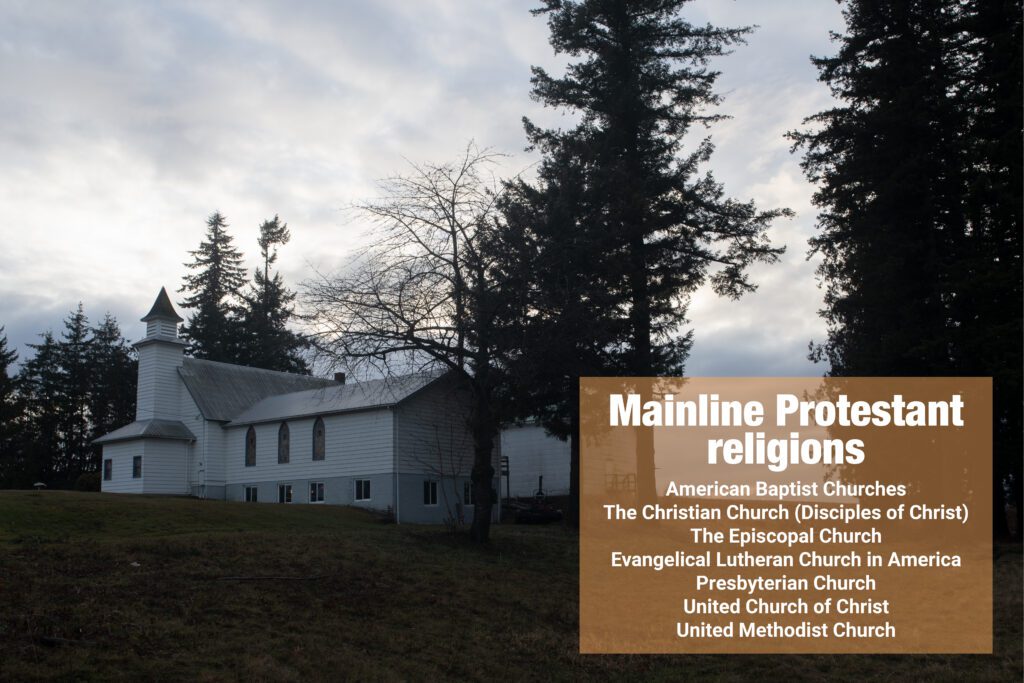

While the church’s closure does not indicate poor health or the looming demise of the Lutheran church, it does mirror a trend researchers began observing in the 1960s: a decline in membership of the seven mainline Protestant religions in the U.S.

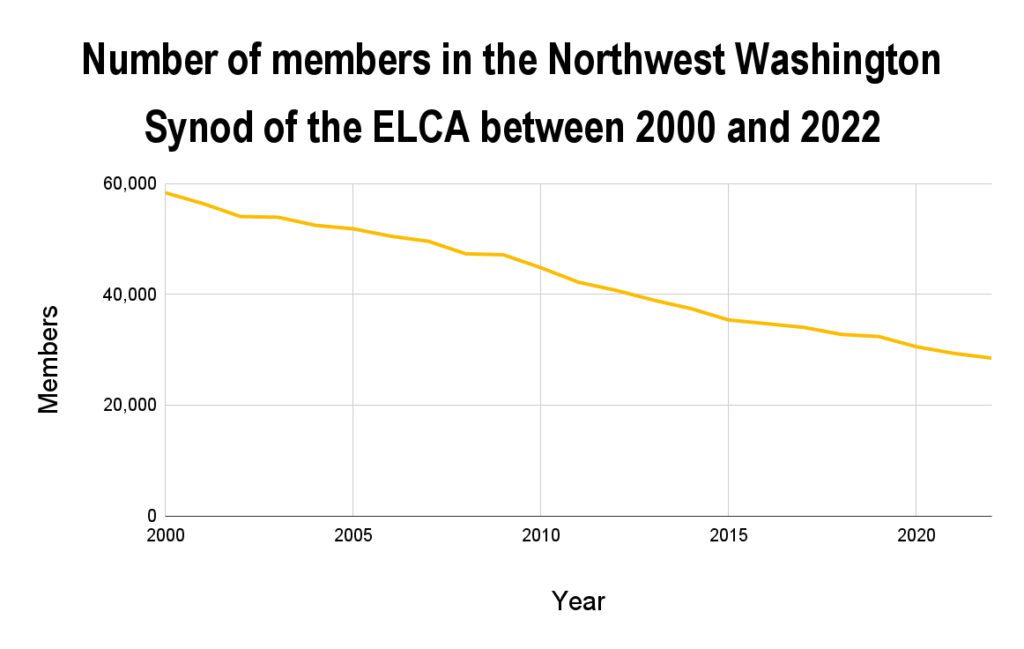

A data analysis that looked specifically at the Northwest Washington Synod shows that since 2000, the number of members has more than halved, from 58,322 to 28,488 in 2022.

While some surveys indicate a general downward trend of people affiliated with a religion, experts point to nuance.

Undoubtedly, a shift is occurring. New religions are emerging. A growing number of “nones” — people who don’t identify with a religion — is difficult to quantify through surveys. Schisms within mainline denominations are creating more liberal or conservative offshoots.

In face of these changes, there is consensus that Christianity isn’t going anywhere, and traditional religions are learning to adapt.

A congregation perishes

Clearbrook’s last Sunday service honored the church’s long history by bringing together current and past members, relatives of founding members and former pastors. They shared stories and laughs before a tearful service, followed by a “communion” of ham and turkey sliders and appetizers in the church’s basement gym.

Parishioners cited various reasons for Clearbrook’s decline — myriad unfortunate circumstances and changing dynamics.

When church member Karel Jahns, 80, joined Clearbrook in the 1980s, the church had around 40 members. Its closure was something the congregation “had seen coming since the ’70s,” she said.

Jahns was the first woman to be president of the church council, picking up responsibilities as members dropped. She even moved closer to Lynden to be near the church as its members diminished.

Jeff and Kristi Ehlers, two of the remaining members, began attending in 1998, later filling key roles such as liturgist, accompanist, church service assistants and terms as board members.

“As the years went by, people moved away, died,” Jahns said. “Children didn’t stay and went their own ways, and by the ’90s, our Sunday School had ended, so no children to speak of in the membership.” Without Sunday School, area families with children began attending a neighboring church, Immanuel Lutheran in Everson.

Migrations of people from rural areas to cities, and smaller churches to larger congregations, also contributed to Clearbrook’s demise.

Sonja Dyer’s relatives were founding members of the church at the turn of the 20th century, when Scandinavian immigrants dominated the area as homesteaders and dairy farmers. Tending to live animals meant farming families had to live full time on their land. When corporations began buying out small dairies and ranches in the county, many of those families moved away, Dyer said. Berry farms, which didn’t require residents on the land, replaced them.

“It’s by God’s grace we stayed open as long as we did,” Jahns said. “God’s grace and Rod Perry. He was a lifelong member, and he was everything to Clearbrook.”

Perry was a lay minister, meaning he preached but was not ordained in his ministry. A lack of funding prevented the church from hiring a full-time pastor, Jeff Ehlers said, and for as long as he had been attending, the church relied on part-time pastors and lay ministers.

Perry was credited with extending the church’s lifespan by at least 10 years, said Nancy Perry, his widow. When he died of Lou Gehrig’s disease in 2019 at the age of 62, the church’s days were numbered.

Many parishioners also pointed to the rising popularity of “box churches” — large, broadly defined or non-denominational congregations that often include upbeat music, youth services and peppy sermons that deviate from more traditional practices.

In that same vein: “The decline was probably due to an older congregation not wanting to change with the times,” Jeff Ehlers said.

The pews, Ehlers said motioning to the one he was sitting on, are representative of that. As other churches adapted to changing desires, like cozier chairs and pop music, Clearbrook maintained its old-school stiff seating and traditional hymns.

Religion ‘not declining but replacing’

Scholars point to data leaving little doubt that people are leaving mainline Protestant churches. Where they’re going is tougher to define.

The “box-church” worshippers represent a trend since the 1970s of those leaving mainline Protestant groups for nondenominational groups, said Holly Folk, a Western Washington University professor of religious studies.

“For positive or negative, you could argue that the box churches have been intentionally constructed to meet consumer demand,” Folk said.

They’re upbeat, modern, energetic and engaging for all ages.

More than half of all new denominations in the U.S. were formed after 1970, said J. Gordon Melton, author and American religious scholar. Melton, in partnership with Folk, led a study that looked at the number of congregations within three counties in the U.S., including Whatcom County.

The Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies counted 150 churches in Whatcom County in a 2012 census. Folk’s students found an additional 100 unaccounted-for churches. The other two counties, located in Texas and Virginia, showed similar results.

“It is these hundreds of newer Christian denominations that constitute the ‘Others’ — a largely invisible religious community hiding in plain sight in America,” according to the study.

Nondenominational churches and immigrant congregations make up part of those “invisible” churches; they often follow the same developmental pattern of starting in one’s home, then growing in size to rent or buy a building.

“Ignoring their presence has contributed substantially to a popular misconception that religion life has been on the decline in the United States,” according to the study.

Well-known public surveys like from Pew Research Center and Gallup point to a shrinking population of religious people as a whole in the U.S. In a 2021 survey of nearly 4,000 people, Pew asserted 30% of U.S. adults are non-religiously affiliated, up 6 percentage points from 2016.

“There’s a whole bunch of phenomena pertaining to participation that people in the U.S. and also scholars in Europe have noted that make counting people authentically pretty complicated,” Folk said.

For instance, those who identify as spiritual, but “not religious,” are difficult to track because religions like Wicca or Tibetan spirituality might not be reportable via a survey.

Melton said Pew measures religious self-identity as affiliation. Yet, those without a clear religious self-identity — those religious “nones” — may still believe in a higher power. In Pew’s latest survey, out of those who categorized themselves as “no religion,” 29% still said they prayed either daily (13%) or monthly (16%).

“I see problems in trying to capture people who are less officially tied, who a generation ago, would’ve claimed the identity of their parents, and who are now more loose about that,” Folk said.

Johnson refers to those individuals as religious “umms.” They can be people who may not attend church every Sunday but did as a child, who go to services when they visit home, or who want to involve their own children in a religious group.

Then there are religious “dones” — people turned off of religion entirely, often after harmful experiences, Johnson said.

Inviting in those spiritual “nones,” “umms” and “dones,” has been a focus of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) for more than a decade.

Part of Johnson’s role is to find ways to start new congregations. “Can we reach out to people who aren’t currently involved in a church setting? We have a number of ministries that are focused that way,” Johnson said.

One of those is Echoes, based in Bellingham. The ministry was born at Bellingham Pride in 2013. Some of the participants are coming out of church trauma and harm, Pastor Emma Donohew said.

Echoes meets on Mondays in pubs, outdoors, during work parties, craft sessions, and candlelight symposium-style meetings. And, it’s inclusive. Donohew grew up and was ordained in the United Methodist church, but left in part due to the church’s stance on LGBTQ+ ordination.

“Not every church needs to look the same,” Donohew said. The ELCA is adapting to that mindset.

At a Monday, Jan. 23 Echoes candlelight service, a small group of members gathered in a circle. Donohew led them through a mindfulness practice before diving into a reading.

Rich and Chris Sanders said they left their church to join Echoes, disaffected by a lack of inclusivity and diversity.

“The situation has changed in that they’re going to have to become more diverse, or not survive,” Rich Sanders said. “If there’s a future, that’s where it is.”

Although they stayed within the ELCA, the Sanders are part of a population who chose to leave their congregation in search of something that better aligned with their values, whether they be radically inclusive or radically conservative.

The trend often favors the latter, Melton said.

“When we look one-by-one at the theology of the new churches, they are overwhelmingly conservative in their theological outlook,” he said in an email.

Folk believes mainline Protestantism is increasingly emulating evangelicalism.

“They’re trying to do the ‘come as you are’ outreach that has happened, that’s worked well for evangelicals, while still staying within the framework of liberal Protestantism,” Folk said.

How that will affect declining membership in Protestant religions is unclear, but Folk is confident those religions won’t go extinct.

“Most [groups] are aware of their numbers. Most large groups have people working on the membership problem because at the end of the day, you need your shareholders,” Folk said.

It’s easy to get lost in data and a swarm of numbers, Folk added. But it’s important to remember that within the walls of each congregation is a community, whether it be five people or 500.

“The churn I can look at dispassionately doesn’t stop the fact that there’s a human cost to this,” Folk said.

The human cost

Asked what she hoped for in Clearbrook’s last Sunday service, longtime member Jahns put simply and tearfully, “To praise God and thank him for all he has done.”

As Pastor Lorant read the declaration of leave, sniffles filled the sanctuary and tears streamed. Parishioners sang with heavy voices “How Great Thou Art.”

“With thanks to God for the work accomplished in this place, I declare this building to be vacated for the purposes of Clearbrook Lutheran Church in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit,” Lorant said.

As people filed out of the sanctuary, the church’s old bell tolled.

Within Clearbrook’s walls, members celebrated joyous occasions, honored those who died, found their husbands or wives, made lifelong friends.

“It’s just a place where they grew in God’s love and shared the good times and the bad times of life, celebrations, the Christmas seasons — just an extended family,” said Jahns, who had her 25th wedding anniversary, both her children’s confirmations, her grandchildren’s christenings and her husband’s funeral service at Clearbrook.

In years past, Clearbrook was a place of harmless ruckus and youthful energy.

“It’s an end of an era,” said Dyer’s brother Eric Leninger, who reminisced about riding his bicycle down the carpeted staircase leading into the gym as a boy.

“It wasn’t just a spiritual connection, it was a life connection,” said Dyer, a relative of one of the church’s founding families.

Clearbrook’s worn wood, frayed carpet, dated furniture, dog-eared hymnals, smudged stained glass and chipped paint told a 120-year-old love story.

And more than a century of memories make for a gut-wrenching goodbye.

“It’s going to be a void,” Jahns said. “Everyone loves our little white church in the country. Hate to see that end.”

A previous version of this story misstated the number of baptisms per year in the Northwest Washington Synod. The data reflects the total number of those baptized, or members. The story was updated on Jan. 29, 2023, at 8 p.m. to reflect this change. The Cascadia Daily News regrets the error.