Editor’s note: Title IX at 50 is a three-part series exploring and reporting on how the federal law has impacted and changed lives of Whatcom County women in sport over the past half-century. At times controversial, the legislation has gone a long way toward leveling the playing field for girls and women since its inception in 1972. Today’s Part I details Title IX’s significant influence on Western Washington University and local sports figures. Due to broad public interest in this subject, this series has been made available outside the newspaper’s paywall as a public service by Cascadia Daily News.

As Western Washington University’s women’s basketball team returned home from the 2022 NCAA Division II national championship game in March, team members climbed off their police-escorted charter bus from Sea-Tac airport and celebrated with Bellingham’s mayor, Western’s president and around 100 friends and family. Players signed posters and were honored with an imaginary toasting of glasses, fresh off what head coach Carmen Dolfo described as a difficult but exciting season. The Vikings finished runners-up in the national tournament and upset four of their five opponents on a fairytale run to the finals in Birmingham, Alabama.

Fifty years ago, a women’s college basketball team would have struggled to find the funds to fly across the country for a national tournament. A few years before that, teams may have struggled to find a national tournament at all. In 1971, the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women had just been established to administer women’s national competitions. Colleges weren’t required to fund women’s teams proportionally to their men’s teams — or at all.

Title IX changed that.

Signed into law in 1972, Title IX dramatically altered present and future opportunities for girls and women in sports. The legislation’s protections, combined with Northwest Washington’s athletic culture and an array of influential changemakers in Bellingham sports history, set a precedent for girls and women’s sports to grow in the area. It’s a rich history, and still growing.

‘I’ve sold my last damn cookie’

Change didn’t happen overnight. When Western’s women’s basketball team earned bids to national competitions a half-century ago, in 1972 and 1973, the athletes had to raise funds with bake sales and car washes — something common nowadays for a youth rec team, not a college program. Then-head coach Lynda Goodrich said financial support of the programs still took time, even though Western had been an early proponent of women’s athletics. But in the wake of Title IX passing, Goodrich knew a new era had begun.

“I’ve sold my last damn cookie,” Goodrich recalled saying to athletic department staff. “If you want to have athletics, you’ve got to spend the money in supporting it.”

Over the next 50 years, educational institutions have — yet sometimes grudgingly.

No discrimination on basis of sex

Title IX doesn’t actually mention anything about athletics. Passed as part of the Civil Rights Act’s Educational Amendments, the law states that, in U.S. educational programs that receive federal financial assistance, no one should face discrimination “on the basis of sex.” The entire law is 37 words. None of those words are “sports” or “athletes.”

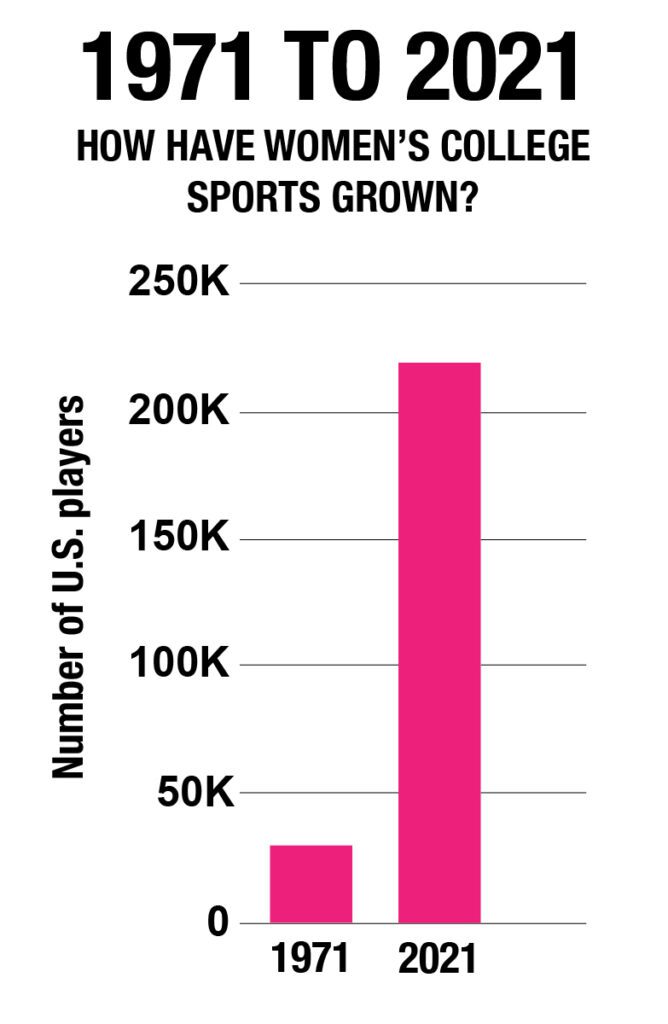

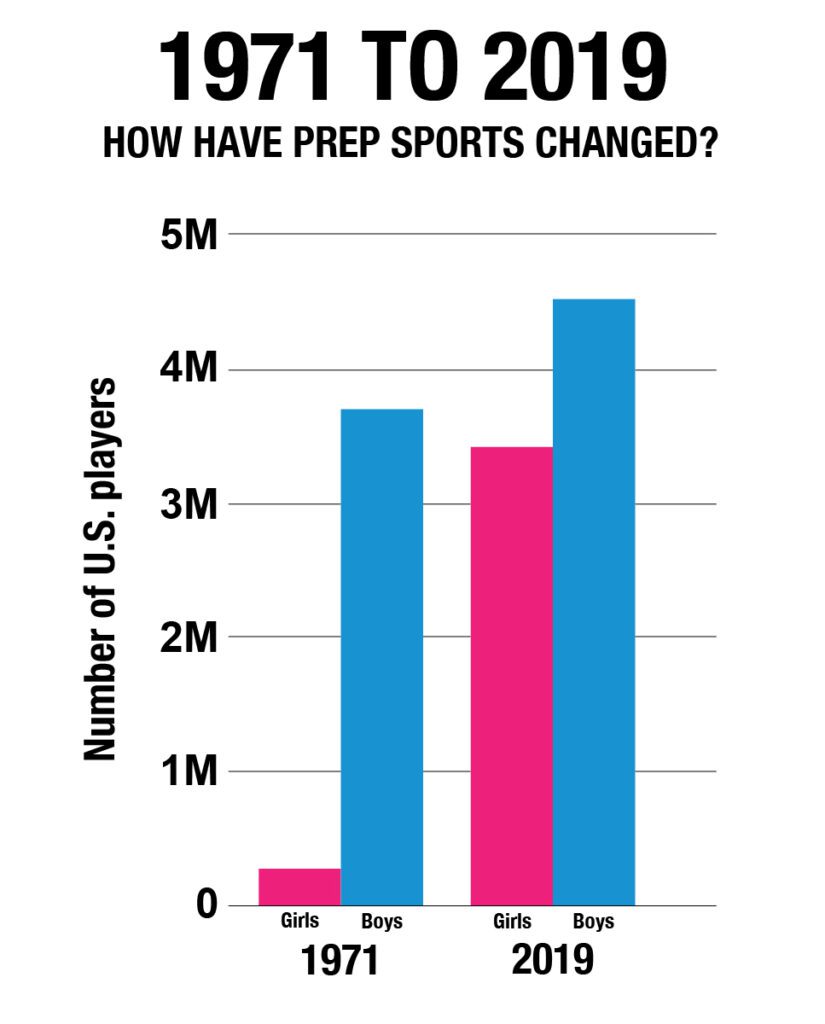

Yet because schools and athletics are closely intertwined in the American education system, the link between Title IX and women’s sports would quickly become apparent at both the high school and collegiate levels. The number of girls playing high school sports has increased by nearly 12 times since 1971, and for college athletes, more than seven times.

These growing numbers mean that more girls and women are exposed to the benefits of sport. Increased confidence, health, leadership skills, grades and professional opportunities are among the reasons a community should care whether girls have access to sports, according to the Children’s Medical Group.

Western ahead of the (women’s) game

In the late 1800s, more than a century before Western Washington University reached that first NCAA Division II women’s basketball finals in 2022, female college students across the United States began playing organized sports. At Western, some female students, wearing pleated skirts and winter stockings, took up skiing and archery in the early 1900s, already tuned in to the outdoor recreation culture of the Bellingham area. Archives also show Western women’s teams in basketball, baseball, field hockey and softball.

These opportunities, though, had little funding, formal organization or legal protection. That would come later with the 1972 passage of Title IX. Until then, women’s sports were largely dependent on parks systems or relegated to intramural “play days,” with little interscholastic competition at the high school or college levels.

Longtime Sehome High School tennis coach Bonna Giller, 64, who played all three girls sports offered by Burlington-Edison High School before graduating in 1976, said her high school basketball coach also drove the team bus to games. The volleyball and basketball teams used the same uniforms, handmade by the players — white T-shirts dyed yellow with iron-on numbers.

Goodrich said in the years after Title IX passed, Western’s administration’s support of women’s sports allowed them to thrive at the school and set a precedent for the following decades. Physical education department chair Margaret Aitken, head of the athletics program at the time, “was a very strong supporter of women and women’s rights,” along with other administrators like former university President G. Robert Ross, Goodrich said.

“When you get people in positions that can help influence, that makes it happen,” Goodrich said. “Western was, I believe, at the forefront.”

According to Western Washington University’s Carver Memories series, former Vikings volleyball captain Terri McMahan sent a letter to every public university in Washington when she was entering ninth grade in 1969, asking what athletic opportunities there were for women at each school and inquiring about the schools’ education programs.

Only one response answered all her questions — a letter from Aitken.

McMahan went on to have a hall-of-fame career as a coach and athletic director, shaped by influences like Western physical education professor Chappelle Arnett, who taught a week-long workshop on Title IX and the future of women in sports to Western students.

Most schools fall short

Today, Western’s number of women’s sports participation spots is equal to, or even slightly over, the percentage of female-identifying students in its student body. That makes Western among the minority of universities matching or exceeding the standard monitored by the U.S. Department of Education, with 87% of universities failing to meet this proportion, according to the department’s 2019 report. While those schools are not necessarily in violation of Title IX — other criteria can be met to stay in accordance with the law (see “Title IX’s three-pronged approach” below) — the fact remains their student-athlete population does not demographically reflect the student population at large.

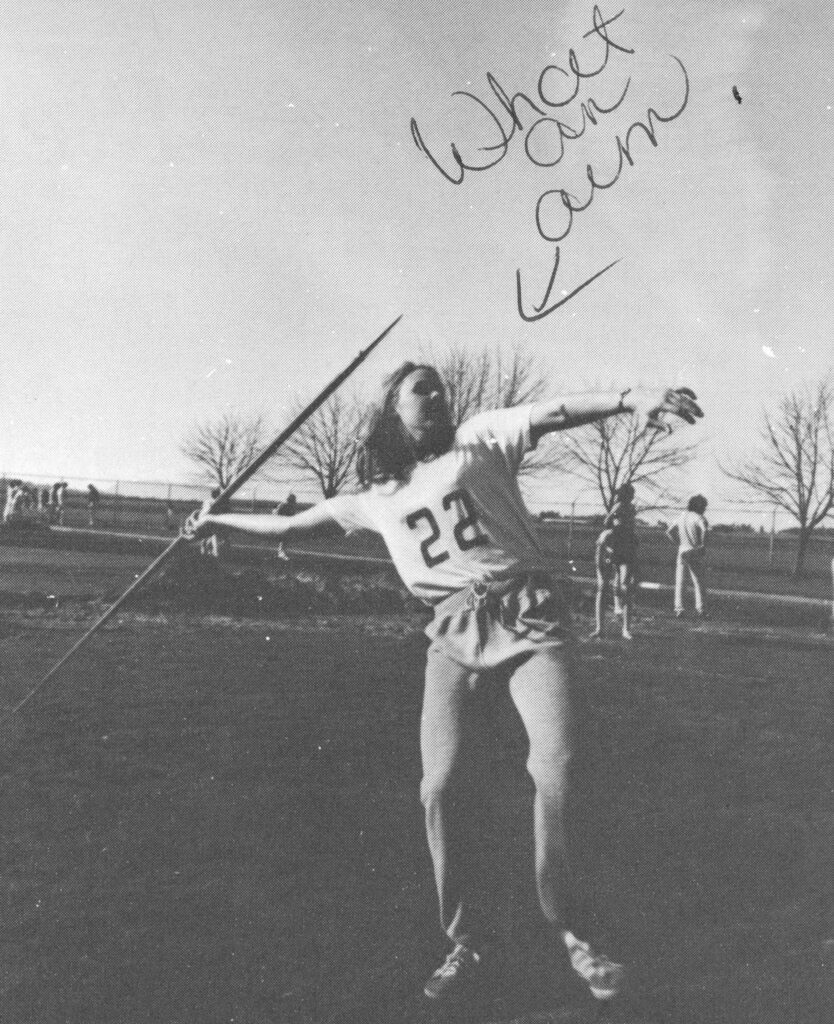

Monika Gruszecki, a national champion javelin thrower who graduated from Western in 2011 and now works in NCAA compliance at the University of Arizona, added that the general culture of the Whatcom County area seems to encourage girls to take up sports, and many of these girls are recruited locally to compete at NCAA Division II schools like Western and other schools like Whatcom Community College.

“I think that for girls in the Northwest, it’s cool to be female and shredding it down a mountain on a snowboard,” Gruszecki said. “That’s what it was like, in middle school, in high school, and that kind of a culture, it breeds some kickass athletes.”

Gruszecki grew up wrestling, in addition to playing other sports. At age 13, when a coach at a local wrestling camp did not allow her to participate in a tournament with the boys, she wrote a letter to the United States Wrestling Federation. The federation, remarkably, invited her to Oregon to participate in the United States women’s wrestling team’s joint camp with Canada, where girls and women were preparing for the World Championships in Greece.

“That was the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life,” Gruszecki said. “Hands down. They woke us up at 5 a.m. We had to run 6 miles, and then we had to wrestle until 8 and then we got fed breakfast. And then we wrestled until noon. And then you slept. And then you wrestled again.”

Gruszecki said she still has the shirt from the camp.

Whatcom CC, Western tap into local talent

Looking for these tough and hardy local athletes, NCAA DII schools like Western and community colleges including Whatcom Community College often recruit locally, with smaller recruiting budgets compared to average NCAA Division II schools. Twelve of the 13 players currently listed on Western’s women’s basketball team are in-state students, and all five of the team’s starters in this year’s historic NCAA tournament semifinal upset over North Georgia played high school ball in Washington.

Western hoops coach Dolfo said nearby areas such as Lynden and Ferndale offer plentiful opportunities for youth sports and, by association, recruiting.

“The whole town goes to the state tournament,” Dolfo said. “It’s just a culture that they have that is really supportive of athletics.”

Scholarship athletes still struggle financially

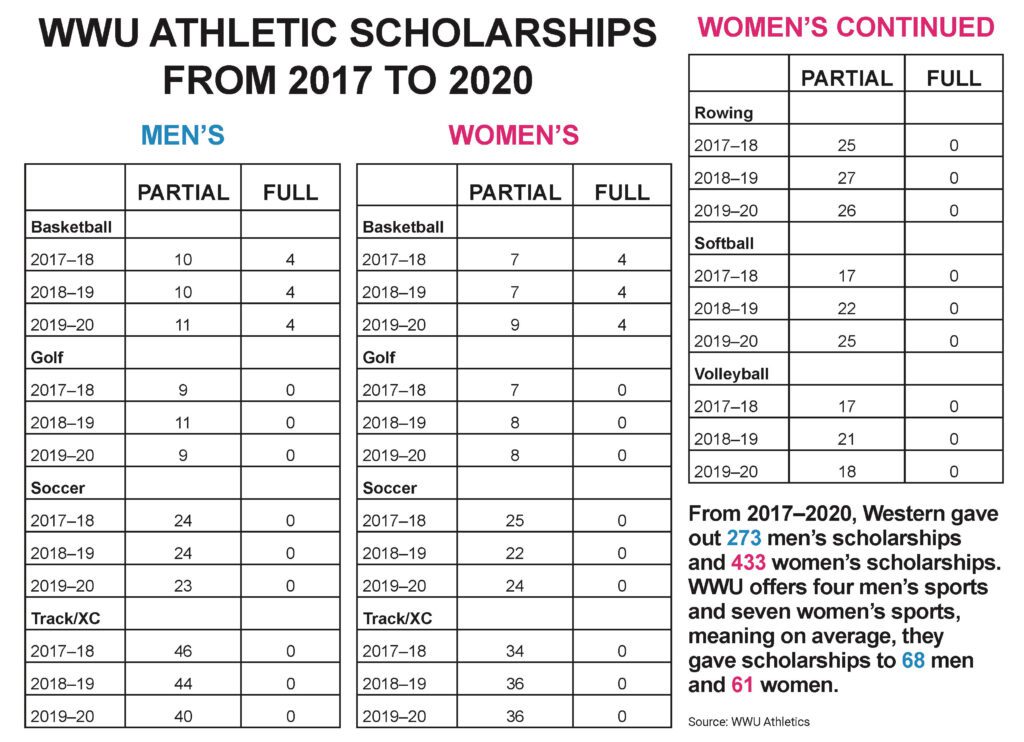

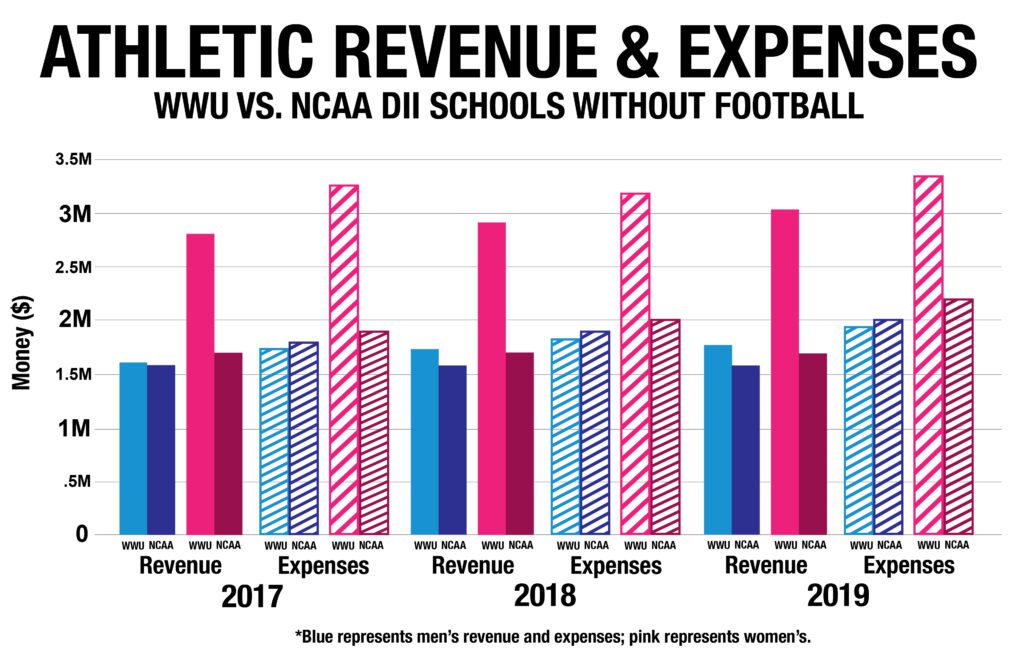

Yet even a half-century after Title IX’s landmark legislation, being recruited on an athletic scholarship doesn’t mean a student has it made financially, especially in Division II sports where the overall budget for women’s sports is smaller than that of the average NCAA Division I school, despite a lesser gender gap between scholarships and expenses.

Sierra Shugarts, the NCAA Division II Women’s Soccer Player of the Year in 2016 — when Western won the national championship — recalled the stress of having to balance a collegiate sport with class and working a job at the local Sportsplex to pay for expenses her scholarship didn’t cover. She said she enjoyed the smaller-college balance between sports and life outside the game, though she knew other girls who transferred from Western to Division I programs seeking to play at larger schools with bigger budgets.

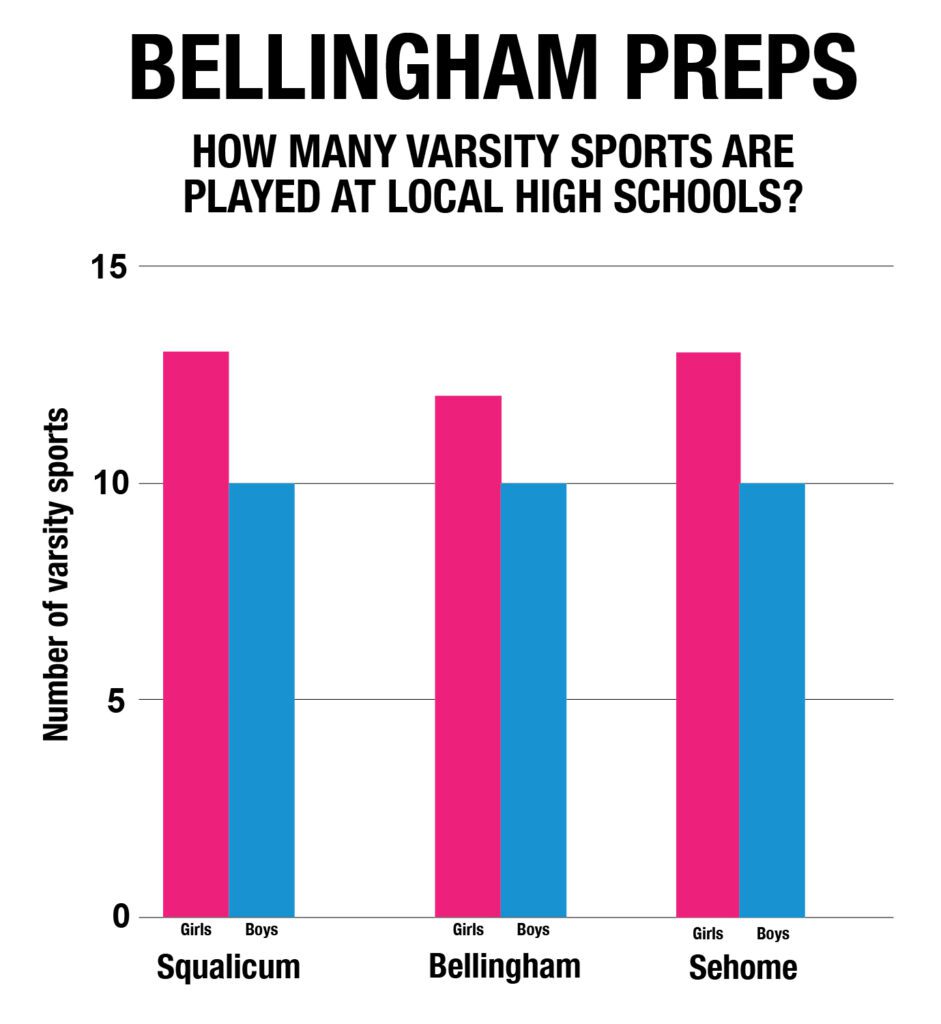

High school sports don’t offer scholarships, with Title IX scrutiny targeted to monitoring fair numbers of sports offered to girls and boys and equal-quality facilities and funding. The three Bellingham School District high schools, Bellingham, Sehome and Squalicum, list 10–13 sports each for girls and boys.

Overall, Giller said while she “felt very respected in high school as an athlete and supported as much as I could be as a female starting sports for the first time,” the improvement in funding and facilities that she has witnessed is something she wants her current athletes to understand, appreciate and keep pushing to improve.

“I used to say to myself … man, I wish I was born about 10 years later, or 15,” Giller said. “That is a mantra a bunch of us used to have when we were younger. But like, no, then you would not have experienced this growth and development … It makes me really, really appreciate where I came from.”

Next week: Title IX at 50 examines the longevity and influence of female coaches and athletes in Whatcom County.

Women’s sports on the air

Network, streaming viewership picking up steam

From more than 4,000 miles away, Western Washington University women’s basketball alum Taylor Peacocke watched her former team compete in the 2022 national championship. In Lisbon, Portugal, Peacocke, playing professional basketball abroad, cheered on the Vikings playing the NCAA Division II quarterfinals in Birmingham, Alabama. It was 2 a.m. in her time zone, and her eyes were glued to a laptop playing the game’s live stream via the NCAA website.

Peacocke had few choices. That game wasn’t televised nationally, but the NCAA Division II Final Four games were available on CBS Sports Network, the same as the NCAA Division II men’s tournament.

Recent numbers have shown that, if networks and streamers air women’s sports, viewers will come. Title IX cannot guarantee equal media coverage and spectator attendance for women’s sports, but increasing viewership numbers suggest an enticing market for further media coverage.

The roadmap exists: Last season’s Division I women’s basketball championship on ESPN was the most-viewed women’s title game in two decades, according to ESPN, with 4.85 million viewers. The tournament itself saw a 16% increase in viewership from 2021.

Some NCAA firsts, at last

A 2021 report, commissioned by the NCAA itself, found that the organization was “undervaluing women’s basketball as an asset,” especially in its perceived lack of TV value. An external review found that the “root financial deal” for the NCAA and its member schools systematically maximized value for the Division I Men’s Basketball Championship while providing lesser quality sponsorships, food and signage for the women’s side. Following the report, the 2022 women’s tournament used the “March Madness” tournament branding for the first time.

This season, also for the first time, ABC will broadcast the 2023 women’s championship game, expecting to capture an expanded audience on the traditional network. Yet, there’s a tradeoff: Due to other “commitments to entertainment shows,” says ESPN, the Sunday, April 2 game will be broadcast at 3 p.m. ET instead of in prime time typical for big events. The 2021 National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) championship also saw a noon kickoff, outside of prime time. What is shown where, and when, matters — the debate continues about the value placed on women’s sports.

No debate about this, though: TV coverage of women’s sports remains wildly out of proportion to men’s. As of 2019, only 5.4% of SportsCenter’s airtime covered women’s sports. That number has barely budged from 1989’s 5%, according to a study by the University of Southern California and Purdue University.

Former Western Washington University athletic director Lynda Goodrich said Western’s sports information department — including current director Jeff Evans and longtime SID Paul Madison, now the department’s athletic historian — have worked to combat this coverage gap locally, though they face limitations.

“I think our sports information department does a great job at getting news out through their website, and before (the) web, before that, it was press releases,” Goodrich said. “But it was up to newspapers and radio stations, the media to pick those up. And, you know, let’s face it, if it were a choice between us or the University of Washington, the University of Washington is going to get the coverage, not us … Whether it’s picked up or not is sometimes beyond [the SID’s] control.”

Former Western javelin thrower Monika Gruszecki said she has seen standing-room-only women’s soccer games and electric women’s basketball games at Arizona where she now works in NCAA compliance. She said media contracts can limit exposure, though social media and new media contracts have allowed more fans to interact with women’s sports.

“I believe one of the arguments that I heard was, well, no one watches [women’s sports],” Gruszecki said. “Well, yeah, if you don’t televise it, no one’s going to watch it.”

This year, both broadcast and streaming of women’s sports surged with well-watched and attended sporting events. In baseball, the 2021 Women’s College World Series outperformed the Men’s College World Series in viewership. In soccer’s 2022 Women’s European Championships, more than 87,000 fans packed a sold-out Wembley Stadium to watch England’s women’s team defeat Germany, setting a new Euros final attendance record for the tournament — men’s or women’s. These recent numbers will almost certainly impact new media deals inked in the coming years.

These days, women are finding ways outside mainstream media to build exposure. Social media has allowed female-run women’s sports channels to increase coverage of women athletes and set the stage for female college athletes to engineer name, image and likeness deals.

Title IX’s three-pronged approach

Some schools fail to comply despite law’s leeway

Meeting the criteria for Title IX is not as simple as having an equal number of women’s and men’s sports. Universities can comply with the federal law in three ways, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

• “A school must provide athletic opportunities substantially proportionate to the ratio of male-to-female students enrolled in the institution.

• If the first is not met, there must be a history and continuing practice of program expansion responding to the interest of the underrepresented sex.

• If the second is not met, the interest and abilities of the underrepresented sex must be fully accommodated.”

High schools and colleges were required to comply by 1978, but the complex and controversial nature of compliance, along with difficulty in enforcement, means discrepancies continue.

As a public university receiving government funding, Western Washington University is required to follow Title IX regulations, which are overseen by the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR).

Based on “three prongs” criteria, Western is not required to offer the same sports for men and women, or an equal number of sports for men and women. It’s also not required to offer equal scholarship dollars or facilities to each sport. However, it must satisfactorily “provide equivalent treatment, services and benefits,” and, if a complaint is filed, the OCR will look at the availability, quality, opportunities and treatment of men’s and women’s sports to see if colleges are in violation of Title IX.

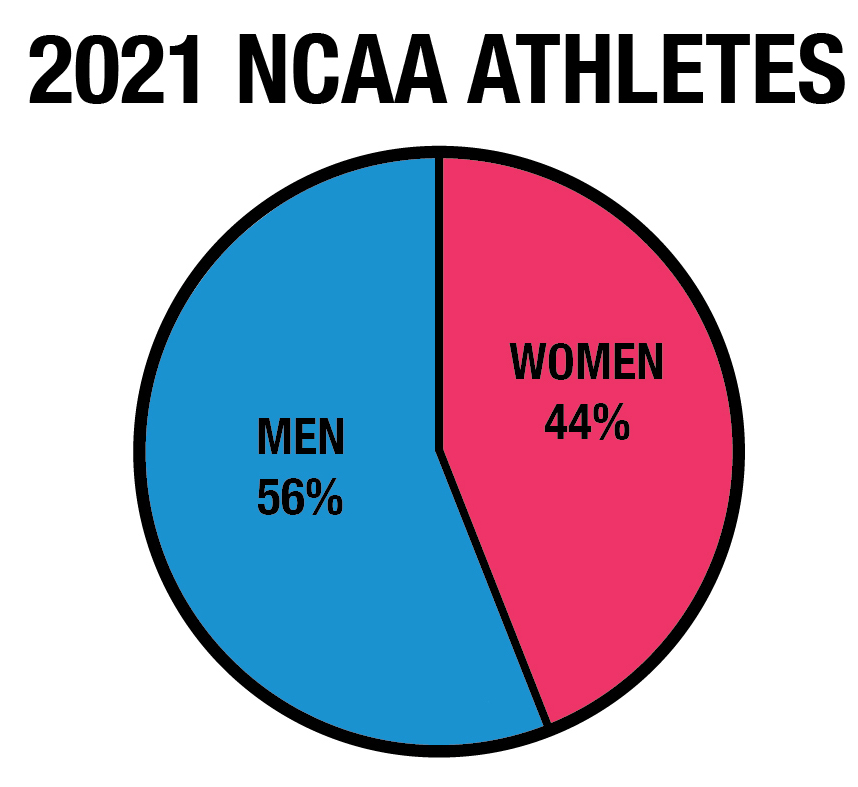

The NCAA may look at whether Western’s number of men and women participating in sports is relatively proportionate to its overall student enrollment breakdown based on sex. As of 2019, 54% of Western’s 292 total athletes competed in women’s sports, and 59% of athletic scholarship money went to female athletes. That’s compared to the 57% of total students that identify as female — a relatively similar number.

If this number was drastically different, the university would have to show that either the difference comes from non-discriminatory practices, such as students paying in-state versus out-of-state tuition, or that it is taking steps to increase opportunities for the underrepresented sex in the athletics program.

In addition to participation numbers, the Department of Education’s interpretation of Title IX considers equal, or improving, treatment of both men’s and women’s sports, from quality of competition to equipment, scheduling, travel allowances, facilities, publicity, housing and training services, among other factors.

However, Title IX hasn’t addressed every issue it set out to solve, both within and outside of its legal scope. In May 2022, USA Today released an extensive report detailing how, nationwide, some universities have double-counted female athletes in indoor and outdoor track, opening up rosters with informal tryouts for athletes who may never compete and counting male practice players as competitors in their women’s sports to give the appearance of equal opportunities.

Is Title IX to blame for cuts in men’s sports?

Economy; outsized football, basketball budgets play a role

Western Washington University no longer has football, but don’t blame Title IX.

Western athletics faced budget cuts as the 2008 economic recession hit. Football was the school’s most expensive sports program. Western was one of five NCAA Division II schools west of Colorado that sponsored football, so the team traveled far and frequently to play opponents, or played each conference opponent twice.

Former Western Athletic Director Lynda Goodrich knew that eliminating football meant financial security for the other Vikings teams, as hard as the decision was to make, especially considering the athletes, alumni and community at the time.

“We looked at all the different scenarios if we kept football, how we’d have to cut budgets of all the sports,” Goodrich said. “The decision was made then to drop football and save the other sports basically. It was a very difficult decision, hard for those kids and the coaches, but in the long run, I think it was the best decision for the program.”

College sports are often cut during financial downturns. When men’s sports are on the chopping block, however, critics often blame Title IX compliance. Yet the dynamic between Title IX and men’s sports is often more complicated than simply one-to-one cuts.

According to Sports Illustrated, the top six sports with the largest decreases in NCAA Division I sponsorship since 1990 are men’s sports: men’s tennis, wrestling, swimming, gymnastics, baseball and soccer. In that same time, the top seven sports experiencing growth were women’s. However, both men’s and women’s college athletics participation has increased overall since the passage of Title IX, as has high school sports participation.

Sports Illustrated and ESPN both reported some university athletic directors citing Title IX as a source of pressure to not cut women’s sports during the 2008 recession and the COVID-19 pandemic — despite the fact some women’s teams were cut alongside men’s programs.

The dynamic most affecting NCAA schools’ athletic budgets isn’t necessarily Title IX. It’s often the most prominent programs on campus: men’s football and basketball.

Yes, these two sports often bring the most money and attention to college athletic programs, but they also pull the largest budget and scholarship allocation. The Washington Post reported that at Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS, formerly NCAA Division I-A) schools, football and basketball received 80% of men’s sports funding, leaving the other 20% split among sports like men’s baseball, soccer, tennis, golf, volleyball, swimming, track and field — if the schools even sponsor those programs.

Many schools don’t want to part with football or men’s basketball for financial or school-spirit reasons. But, for schools where these sports aren’t profit juggernauts, they may be cut like their so-called “minor” sports at other universities. A 2014 NCAA report showed that almost half of NCAA Division I FBS football and basketball programs didn’t generate enough revenue to cover their own expenses, with average annual deficits of $4.2 million and $1.3 million, respectively.

Ultimately, like in Western’s situation, it’s a school’s choice which programs to fund and cut, depending on the student body, its sports programs’ history and other considerations.

Series credits

Reporter Cassidy Hettesheimer was a summer quarter sports intern at Cascadia Daily News. She is majoring in journalism and studying sports media at the University of Georgia, where she contributes to the photo and sports desks of the student newspaper, The Red & Black. Cassidy loves running, reading, playing soccer and photography.

Title IX at 50 project editor Meri-Jo Borzilleri is a 30-year journalist and tomboy from the 1970s who, to this day, still needs to play.