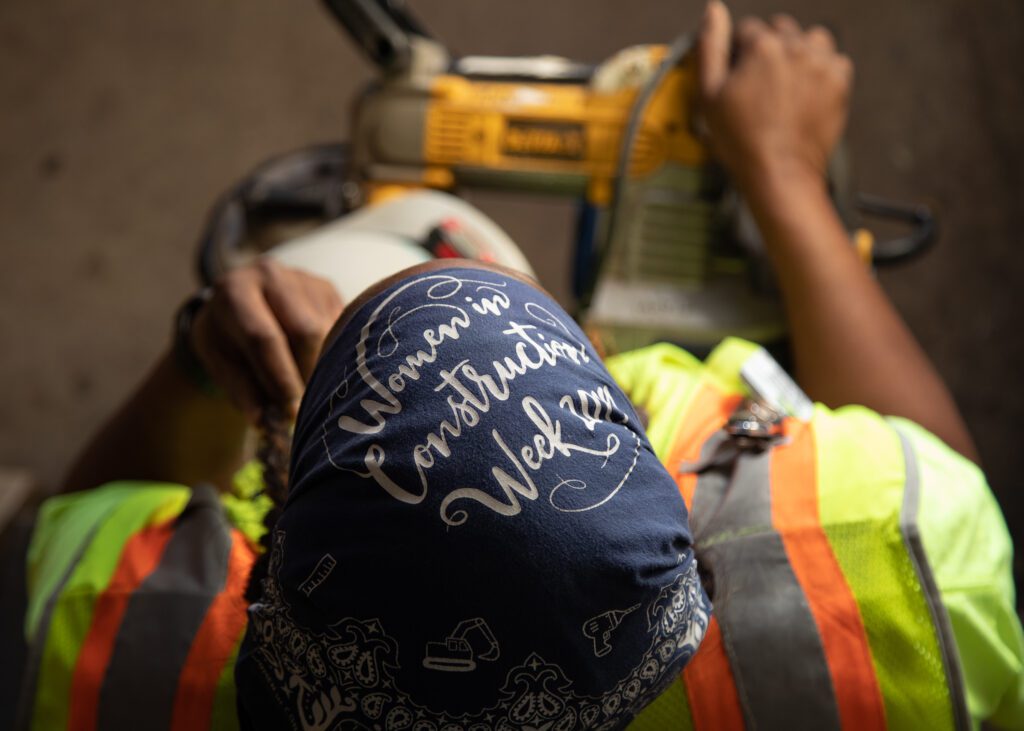

Editor’s note: Women Empowered: Honoring Women’s History Month is a monthlong series of Q&As with regional women in traditionally male-dominated fields. Part one highlights Curtistine Billups, a woman of color who works in construction, and acknowledges International Women’s Day, celebrated March 8.

International Women’s Day, celebrated March 8, emphasizes the need for equity in opportunities for women, not just equality. This year’s theme of the global day, first officially observed in 1910, breaks down the difference between the two words: while equality demands equal treatment for all, equity considers a person’s circumstances.

Equity is intersectional, meaning gender, race, socioeconomic status, sexuality and more are taken into account, and it can be defined as giving someone everything they need to be successful, according to the International Women’s Day campaign.

Some state industries, like trades jobs, have adjusted hiring to meet diversity ratios — a set proportion of women and women of color in the workforce they must reach in order to receive government funding.

Those ratios, and a push for more diversity in the workforce are part of the reason Curtistine Billups, a 55-year-old from Everett, landed her current role as a pipefitter 11 years ago.

Through the United Association Local 26 and 32 unions, she has worked up and down the Interstate-5 corridor. Like all apprentices, Billups had to complete five years and 10,000 hours before she could become a journeyman.

As a Black woman who came to the male-dominated industry in her 40s, pipefitting was an intimidating career. Still, Billups hopes more young women, particularly women of color, feel empowered to enter construction fields. Cascadia Daily News caught up with Billups for a Q&A session in her Everett apartment on March 7.

How long have you worked as a pipefitter, and how did you get started?

Eleven years. I got in when I was 44. I was old. I started out being in the medical field at 17 in college. I became a nursing assistant and spent the last like 24 years doing that. When I was 42, I decided I wanted out. My mom said, ‘Why don’t you move home? You’ve always wanted to weld. Go to school and take some welding classes.’ So I moved home, finished college at 44, and then Local 26 needed female and minority women — the ratio wasn’t correct and they needed to fix that. That’s how I ended up being a pipefitter.

What interested you in welding?

My grandfather actually was a welder in the Army. And I used to watch all the time growing up ‘How it’s Made,’ and I saw them making buildings and all that, and I thought, ‘Oh my god that would be so cool.’

What changes have you seen in the industry over the years?

Just the last 11 years, I have to tell you they have done a much better job with women than when I first got in. When I first got in, everything about discrimination was down on paper but it wasn’t actually quite into practice at that time. Since then, they’ve tightened up. They’ve been trying to get more women into the trades. I’ve worked with several men who have said they prefer to have women working for them — better attention to detail, and you know you can send them to do something and they’ll get it done.

Can you speak to some of the challenges of being a woman and a woman of color in the field?

You don’t want to paint anybody in a bad light, but there was name-calling. There was the N-word. But I’m older, so I handle stuff like that on my own — I’m used to it. I could cuss somebody out even though I was an apprentice because I was older than most people. Some of the other girls had a rougher time — the smaller, more petite girls. I felt bad for them, but I told them, ‘You gotta stand up for yourself.’ I’d tell them, ‘You just come get me and I’ll stand next to you while you cuss somebody out.’

Why do you feel it’s important to have representation in fields like this?

Especially young Black women don’t know they can do other things. I think it’s important that we give our young people of color other options: You don’t have to be a doctor or nurse and you can make just as much money without being a doctor or nurse. Just as a journeyman, you’re making over $100,000 a year.

How do people react when you tell them what you do for a living?

Everybody’s always shocked. When I first got in, I used to get, ‘But you’re so pretty.’ What does that have to do with anything? What would you think I’d be doing? Are you saying because you’re pretty you can’t work hard, that I should be at a desk, be a secretary? Then I have a lot of women who are really excited for me. And I always tell the younger people, ‘You should do it.’

If you could give your younger self advice, what would it be?

First of all: actually go to class to learn. Number two, I would’ve gotten in my line of work way quicker. I would have done it right out of high school. Absolutely 100 percent. I could be retired right now.

What would you tell young girls who are planning to go into a traditionally male-dominated field?

You’re going to have to have a thick skin. You can’t be offended by everything. I get that we are supposed to be politically correct, but you’re still working with people who haven’t had to be, so you gotta be able to show some grace. And do your homework. Had I looked closer when I started, I would’ve known I was right on this Seattle-Snohomish [County] border, and I probably would have gotten into [Local] 32 first. And that’s only because there’s more people of color in 32 than there is in 26. More people of color and more women. So if it’s somebody we’re talking about who’s Black or any nationality other than white, I’d say definitely switch to an area where it’s going to be a little more comfortable.

Part two highlights Kristi Dominguez, Ferndale School District superintendent.