Recent drug overdose deaths have touched virtually everyone in Lummi Nation.

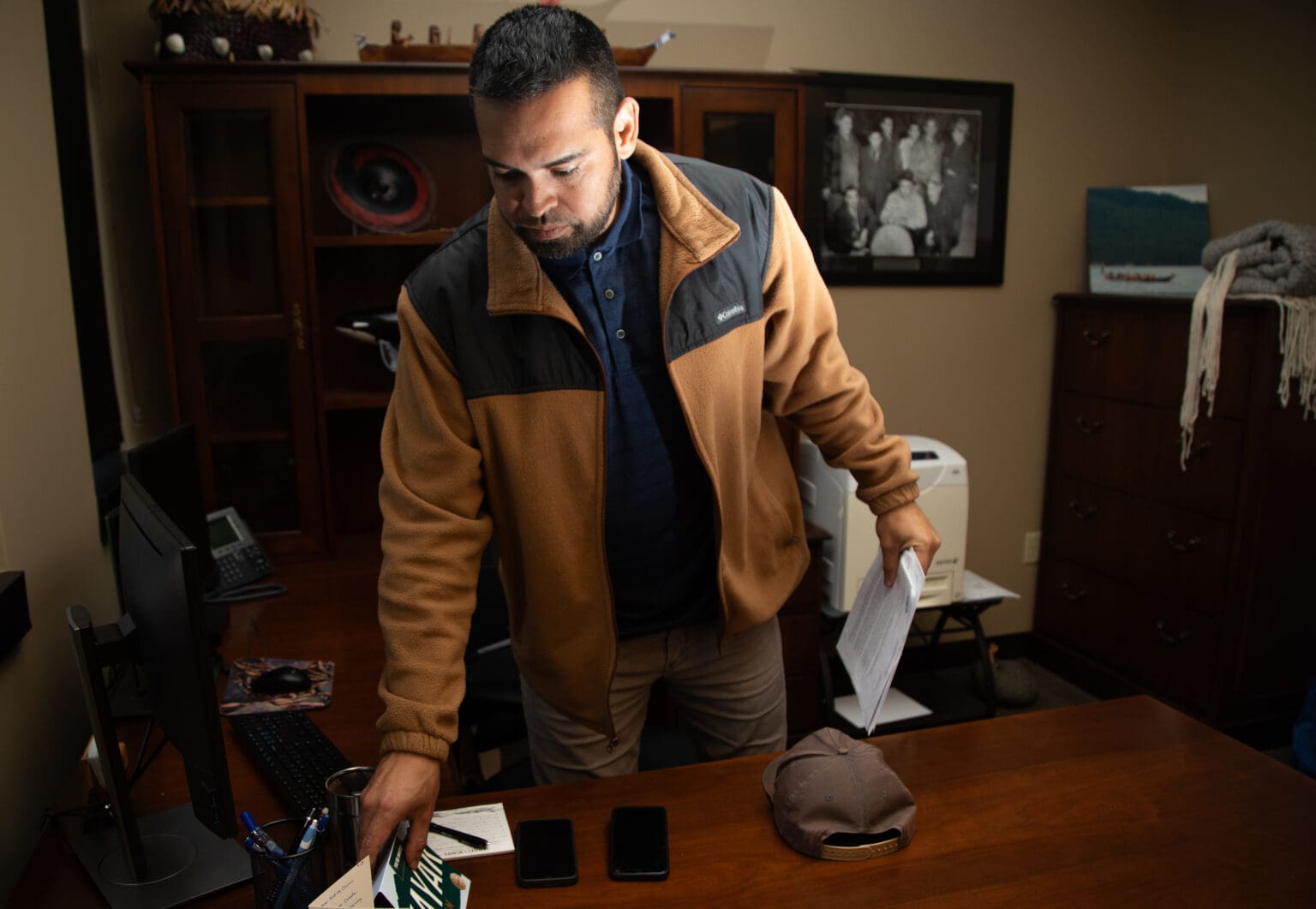

“There’s not one group or family that’s not afflicted with this,” Lummi council member Jim Washington said, speaking in the “war room” at Lummi headquarters after Chairman Anthony Hillaire recounted the recent toll: three deaths within 24 hours, and four or five, as he recalled, within 48 hours.

At least seven tribal members died of overdose over two weeks in late September.

Hillaire lost members of his own extended family. Toxicology results are still pending, he said, but Lummi leaders are confident that fentanyl, or an even stronger opioid called carfentanil, is what killed their people.

“They were family members — brothers, sisters, cousins and parents,” Hillaire said. Some of the recent deaths were among both men and women, in their 30s and 40s, he said.

In the war room, a former executive office on the second floor of the Council Operations building, Lummi Nation’s strategy for combatting opioids is written on a whiteboard wall.

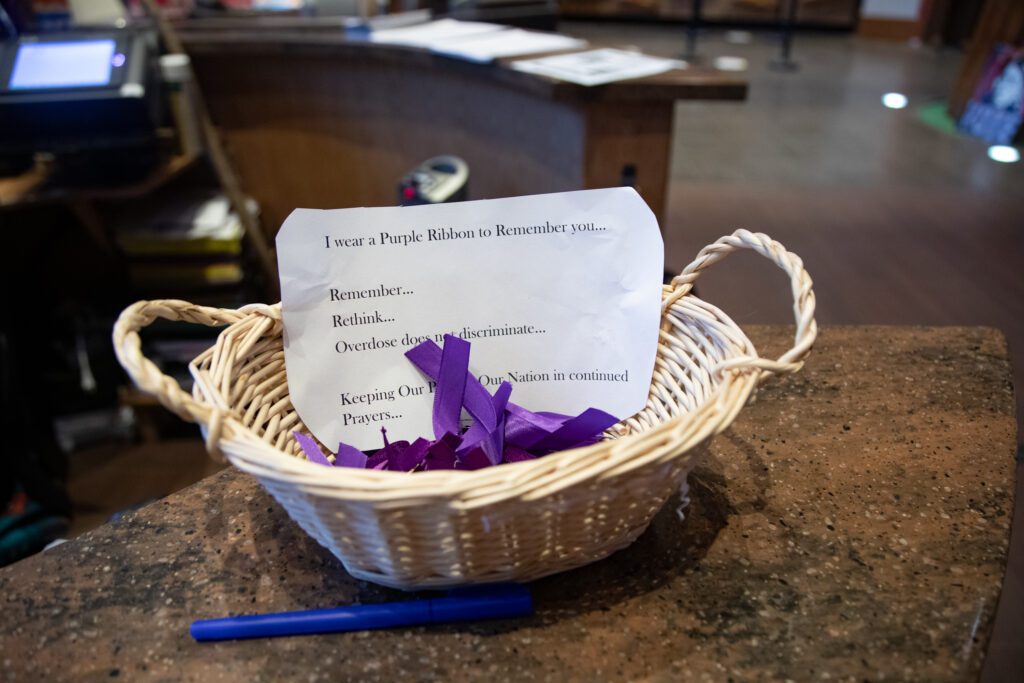

Downstairs in the reception area, the chairman’s aunt, Maria Hillaire, handed out purple ribbons in memory of the lives lost to fentanyl.

Placards in the lobby display hearts with the words, “Overdose doesn’t stop just one heart.”

Overdose data wasn’t immediately available for Lummi Reservation, which has a population of about 5,200 according to 2021 census figures. But county statistics suggest opioid overdoses have skyrocketed in recent years. The Whatcom Overdose Prevention website shows 27 opioid-overdose deaths among county residents in 2020 and 32 in 2021.

Last year, 91 people died in the county from overdose, considering all types of drugs including alcohol, according to medical examiner figures.This year, Whatcom County has already seen 91 drug-overdose deaths through September, with some of those unconfirmed.

Emergency actions

The Lummi Indian Business Council declared an emergency over the fentanyl crisis on Sept. 21, as Hillaire announced in a three-minute video posted to Facebook.

As part of its response, Lummi police have been stopping traffic at checkpoints randomly, day and night, on the reservation. In the video, Hillaire called them “public safety zones.”

Officers assisted by police dogs have been searching cars for drugs at two locations: the roundabout at Kwina Road and Haxton Way, and Lummi Shore Road toward the south end of the reservation.

Police haven’t found drugs during these stops yet, Hillaire said Tuesday, Oct. 10. However, police were able to quickly divert a K-9 from a checkpoint to a traffic stop at another location, where police seized more than 3,500 pills suspected to be either fentanyl or carfentanil, Hillaire said. Lab results on the seized pills were pending.

Carfentanil is a synthetic opioid, 100 times more potent than fentanyl and 10,000 times more potent than morphine, used as a tranquilizing agent for large animals.

Hillaire acknowledged the random stops and searches might conflict with state law, which requires police have a warrant and probable cause before searching a car without the driver’s consent.

“We have policy analysts looking into it for us,” Hillaire said. “That many deaths in that many hours should be enough probable cause to take action.”

A Whatcom County Sheriff’s Office (WCSO) statement said the department doesn’t participate in the checkpoints, and it suggested the sheriff couldn’t book suspects from these stops into the county jail.

“Being bound by state law, WCSO cannot participate in these roadblocks,” sheriff’s office Public Information Officer Deb Slater said in an email. “Bookings at the Whatcom County Jail will be done on a case-by-case basis, based on the probable cause and current booking restrictions.”

County Prosecutor Eric Richey said his office couldn’t take criminal cases stemming from Lummi Nation’s checkpoints.

“Any evidence obtained at those roadblocks would be inadmissible in a state court prosecution,” Richey said Friday, Oct. 13 in an email. “My office is unable to charge any crime where evidence of that crime is obtained at a random roadblock, whether those are drug offenses, DUIs or any other offense.”

Hillaire said Lummi Nation is prepared to go beyond making random traffic stops. It may block the main thoroughfares through the reservation altogether, he said.

“If we have more deaths, more overdoses, we will shut down (the roads),” he said. “We hope to have the support of the county.”

“In initial conversations, they are supportive of what we are trying to do. They share our concern,” Hillaire said.

Kwina Road, Haxton Way and Lummi Shore Road are used to access non-tribal homes and businesses on Lummi Island, via the ferry terminal at Gooseberry Point.

Whatcom County Executive Satpal Sidhu’s public information officer, Jed Holmes, said he wouldn’t comment on hypothetical road closures. He did say the county hasn’t received any complaints from ferry users about the checkpoints already established on the way to the terminal.

Hillaire said the response to the checkpoints from the Lummi community has been favorable.

“We’ve gotten some good feedback from community members, even people who are being stopped,” he said. “They appreciate us doing something.”

Lummi law enforcement is also bearing down on suspected drug houses and dealers, Hillaire said — with some outside help. The chairman said U.S. Sen. Maria Cantwell helped the tribe obtain the support of “a couple” Federal Bureau of Investigation agents as it confronts its fentanyl crisis.

“While we do not disclose the number of investigators we have working specific violations, we are partnering with the Lummi Nation, as well as other tribal departments in Washington, to address violent crime on our state’s reservations,” said Steve Bernd, public affairs officer for the FBI’s Seattle office.

The agency considers drug trafficking a violent crime, Bernd said.

Squatters evicted

In another step connected with its emergency declaration, Lummi Nation took ownership of three adjacent lots at 2508 MacKenzie Road with a single-wide mobile home, formerly owned by Dirk Muntean. The former owner’s listed address on county property records is a P.O. box in Ravensdale, King County. The lots were occupied by squatters, according to Lummi officials.

“We had concerns of drug activity happening there, and quite a lot of people there,” Hillaire said. “We just evicted them, kicked them off the property.”

The eviction was announced in September, but longtime residents of 2508 MacKenzie Road were on the property Tuesday, Oct. 10.

Three of the residents — Holly Wynne, her son Dave Dawson and Dawson’s fiancee Aimee Stone — said Tuesday they had been handcuffed the previous week and asked to leave, but they had not yet received an official eviction notice. Some Lummi police officers have tolerated their presence on the property, they said.

“All they needed to do is ask nicely and give us a notice, and we’d be gone,” Wynne said.

Beyond the tribe’s immediate response to the string of drug-related deaths, Lummi officials hope to fast-track funding from state and federal governments. Leaders are calling on the governor and the state Legislature to declare their own fentanyl crisis — same with the Biden administration in Washington, D.C.

In May, the Lummi Nation hosted a two-day statewide summit in Whatcom County to address the opioid/fentanyl crisis with leaders from 28 tribes, Gov. Jay Inslee and Attorney General Bob Ferguson participating.

The 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott, between the United States, Lummi Nation and other tribes, grants Indigenous people a federally guaranteed right to health care, in addition to education, and the right to fish and hunt in their historical territories.

Hillaire said now is the time for the federal government to honor that treaty and fund a secure detox center for patients who are deep in the throes of drug addiction.

The tribe opened a temporary stabilization and withdrawal center with seven beds earlier this year. A new secure center would have 16 beds at least, Hillaire said, and “would be able to help people with severe substance use disorders.”

Tribal officials have been lobbying for the facility for years, the chairman said.

“A big part of the hurdles in front of us is having to educate every place we go of the rights promised to us,” Hillaire said. “We left our original lands in exchange for these rights. It’s literally just a way to honor that promise.”

Lummi council member Nickolaus Lewis, who is also chair of the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board, said opioids have killed more Lummi members than COVID-19.

He noted that U.S. governments have historically underfunded Indigenous tribes, which taught them how to be more efficient with fewer resources. During the pandemic, for example, Lummi Nation was able to vaccinate its own community in addition to people at Ferndale School District and other non-tribal institutions locally.

Lewis, like Hillaire, called for immediate government funding for the proposed larger detox center.

“Just imagine what we could do if we were fully funded, and we had others get out of our way,” he said.

This story was updated at 1:43 p.m. Friday, Oct. 13, to include a statement from Whatcom County Prosecutor Eric Richey.

A previous version of this story mischaracterized overdose data in Whatcom County. Figures from 2020 and 2021 were opioid deaths among Whatcom County residents. Data from 2022 and 2023 indicated overdoses occurring in the county for all types of drugs, including alcohol. The Cascadia Daily News regrets the error.